di Elvira Visciola

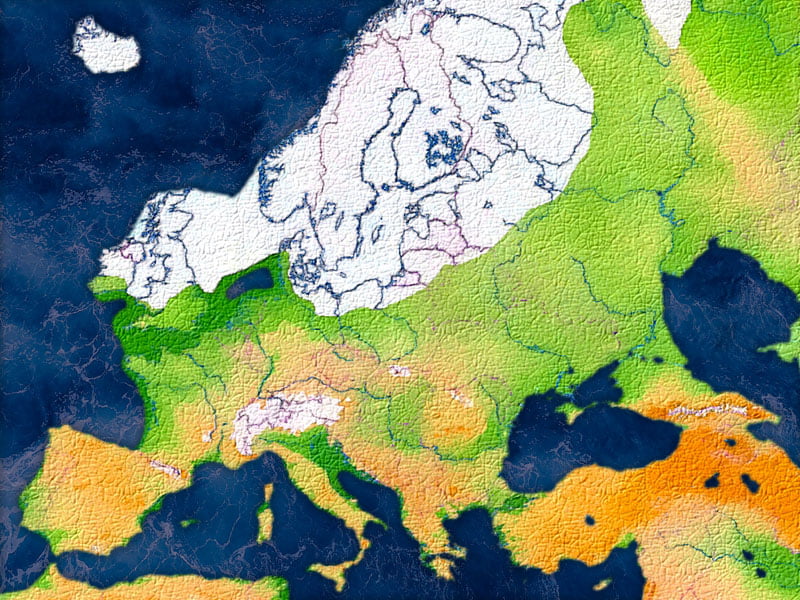

Marija Gimbutas spoke of ancient Europe for the Neolithic, including a vast territory where populations moved bringing with them their own customs and traditions which they transferred to the populations they met. In reality, although the traces are more fleeting and even several thousand years distant, it is possible to speak of ancient Europe since the Upper Paleolithic, precisely because some symbols, tools, uses, customs, materials, movable and wall art have similarities also in places thousands of kilometers away from each other, in areas that academic archeology today tends to treat as diversified. The traces of the Upper Paleolithic that we find in Italy are very similar to those of the Franco-Cantabrian area or the Balkan area, as if the hunter-gatherer societies of the past had developed a spirituality, behavior patterns, ideas and symbols quite similar , whose diffusion was accepted at the level of the European continent if not far beyond.

In the following text I wanted to put together everything that today provides the clearest proof of how much the Italian peninsula was an integral part of a Paleolithic culture in Europe.

In Italy the research on Paleolithic sites took place much later than in other European countries due to the following reasons:

- initially due to erroneous indications from academic archeology; Luigi Pigorini, the greatest palethnologist in Italy at the turn of the 800th and 900th centuries (the period in which the first discoveries of prehistoric finds began) improperly decided that in Italy there had never been traces of the Paleolithic, unlike in France and Spain where the discoveries of the Cave of Lascaux and Altamira contributed to the birth of prehistory, until then ignored; this sort of damnation continued for a long time, even after Pigorini's death, since his followers continued to hinder anyone who even tried to speak of finds dating back to a period prior to the Neolithic[1]. It was only from the 40s that studies on the Italian Paleolithic began to deepen despite the discoveries having taken place much earlier;

- this delay led to a lack of specific studies. Italy is a country rich in history, especially Greek, Etruscan, Roman and beyond, periods on which researches have mostly concentrated; only recently has there been a particular interest in Prehistory, with a greater concentration of research on the Paleolithic and important contributions at an international level.

As evidence of the existence of an important shared visual heritage in a large part of Eurasia during the Upper Paleolithic in the following image is represented an Alca Impennis, a flightless bird of the penguin family, attested in cold climate areas , which became extinct around the mid-nineteenth century due to the hunting that man gave to this animal, as it was considered a coveted prey by collectors who used to put it on display in museums[2].

Returning to the image, it must be specified that there are rare cases in which birds are represented in Paleolithic art, therefore this panel is particularly significant: the auk was found in the wall art of the El Pendo cave in Spain and Cosquer cave in France, as well as examples of movable art on a pebble of Paglicci cave in Puglia dated to about 15.000 years ago, engraved on the walls of Romanelli cave always in Puglia and on a specimen from the site of Laugerie-Basse in France.

This means that the auk impennis was a species that the Paleolithic of these areas, ranging from southern Italy to northern France and Spain, saw and represented it in their caves with the figurative details that distinguish it, testifying of the diffusion of common iconographic motifs throughout the Mediterranean basin and of similar climatic conditions present throughout the territory. From the brown earth deposits of Grotta Romanelli also come two finds of great auk, a humerus and an ulna, exposed to the Civic Museum of Maglie, in the province of Lecce, testifying to the presence of this species in the Mediterranean area.

Wall art: rock paintings and graffiti inside the caves

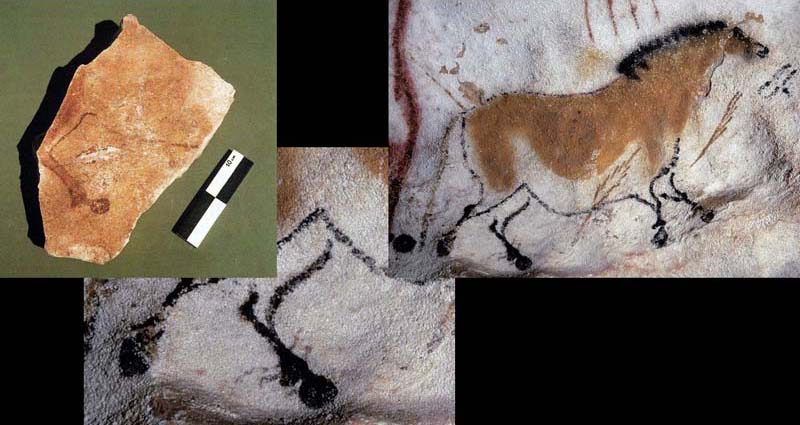

Referring to Paleolithic wall painting, in Italy at present we refer to Paglicci cave in Puglia which, with its specimens, has nothing to envy to other better known European examples.

In particular, the most interesting find is a thick limestone slab found on the floor of the atrium of the cave, probably detached from the vault; it is the slab depicted above in the image at the top left, on whose surface the rear portion of the leg of a horse running towards the right is painted in dark blood red, represented up to the rear part of the belly. The contour is a continuous and uniform stroke, drawn with extreme skill and precision, so as to give the sensation of the third dimension. The figure is assumed to have been about 45 cm overall. and that the find is a fragment of a larger scene painted on the vault of the atrium of the cave, a painting that has otherwise been totally lost. The details represented in addition to the detail of the horse's hoof stylistically recall the artistic productions of the Lascaux cave, in particular the so-called "Chinese horses" of the axial diverticulum, testifying to the presumable existence in the Italian peninsula of a "pictorial school" dating back to the Upper Paleolithic referable to the examples of the Franco-Cantabrian region.

Also from Paglicci cave the two horses painted in red on the wall of a very internal room come from, one of which is represented vertically, as if emerging from the earth, and the other in profile, almost invisible as the image has almost completely faded over time; they are in full archaic style that takes up the Franco-Cantabrian one, with the animals depicted in a static position and the voluminous and swollen bellies to suggest pregnant mares.

Near the wall there is also a series of hands, at least five that are certainly recognizable, some are "positive", i.e. painted by direct impression of the hands smeared with colour, others are "negative", i.e. created by spraying color around them.

A 2009 study conducted by the archaeologist and professor at Pennsylvania State University, Dean Snow, on some Franco-Cantabrian caves (Peche Merle Cave, Abri du Poisson, Font de Gaume, Chauvet, Gargas in France; Altamira, El Castillo and others in Spain) focused on the handprints left inside Paleolithic caves, highlighting that these were mostly small and thin and therefore hypothesized that they belonged to the female genus Homo Sapiens. To corroborate his thesis, he compared the ancient footprints with some more modern ones, highlighting that many of the archaic ones have a long ring finger and index finger and a small little finger, typical, in his opinion, of female hands.

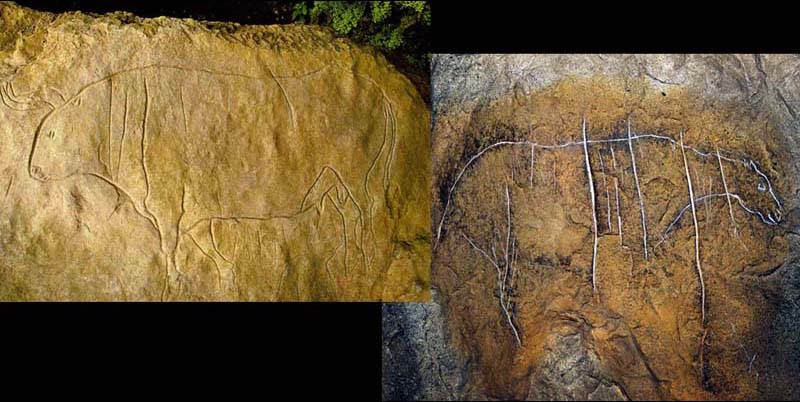

Still talking about wall art, but this time about rock graffiti, a Romito Cave in Calabria an aurochs is represented by exploiting the deformations of the rocky support; often the skilled Paleolithic artists have used the fractures and the convexities of the blocks that suggested some anatomical parts of the animals (for example the back, the tail and the cervical line), as well as using the irregularities of the rock surface to create a sort of three-dimensional effect . A characteristic that returns in many European Paleolithic art productions.

In the case of Cave of Caviglione in Liguria, one of the caves of the Balzi Rossi complex, an engraving was discovered about 7 meters high from the current ground level, with a naturalistic-style figure depicting a steppe horse (called the Przewalski horse) which lived in the final phase of the " glaciation of the Wurm” and similar to the contemporary wild horse of the Camargue. The body of the animal is furrowed by deep vertical incisions, some of which are prior to its execution, so also in this case the graffiti was engraved taking into account these deep fissures, while others are superimposed on the zoomorphic figure.

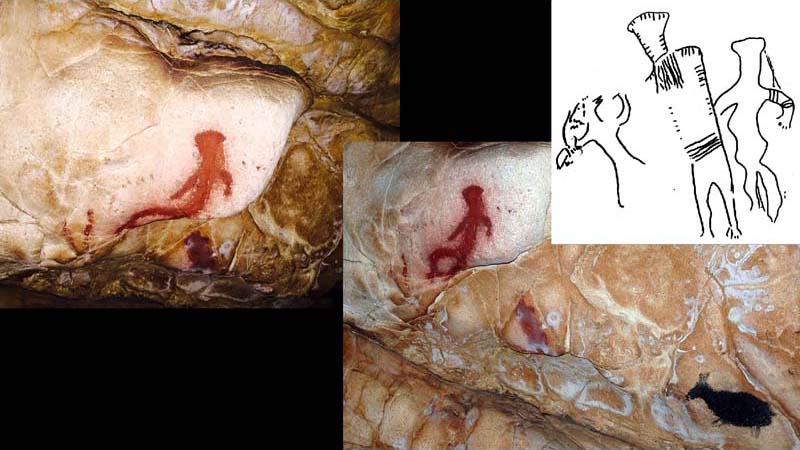

A manifestation of wall art that has aroused heated debate about its interpretation comes from Grotta dell'Addaura in Sicily: naturalistic-style, static figures are represented, with an essential profile, often with few anatomical details (eyes, mouth, sex), but overall a narrative scene is represented, focused on the two characters lying on the ground interpreted in a sort of ritual of initiation or rite for fertility, while the other figures observe the main scene; according to others, the scene represents a human sacrifice, due to the presence of two segments, one between the shoulder and the buttocks of the first character and the other between the shoulder and the feet of the second character, which suggest the pose of the "incaprettati".

An interesting interpretation of the scene mentioned is the one described by the paleontologist Maria Laura Leone in her book "The phosphenic Grotta dei Cervi” (2009) according to which the figures have been conceived as if they were in motion and the different characters dancing around the two men lying on the ground are actually one or two characters with a bird's beak mask, in the act of a practice shaman facing the only character on the ground, depicted in a double position, probably in the throes of convulsions or even an epileptic attack, typical of someone chosen as a shaman. This panel is unique in Europe today, both for the scene represented, so articulated and decidedly narrative, and for the stylistic characteristics used that have no references either in the Mediterranean style or in the Franco-Cantabrian one.

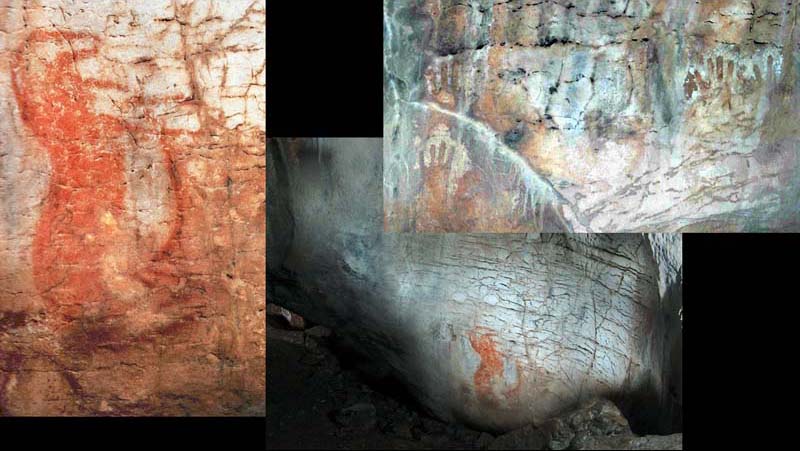

Returning to the wall paintings and speaking of anthropomorphic figures, two interesting images from Cave of Cala dei Genovesi in Levanzo in Sicily: the anthropomorphic figures painted in red ocher have wedge-shaped heads, as if they were wearing a hat or a mask, they have no facial features and seem to emerge from the depths of the earth, as in the case of the horse in Grotta Paglicci. The anatomical imprecision that characterizes them and the scarcity of anatomical details may recall the anthropomorphic paintings of the Franco-Cantabrian region.

At the foot of the back wall of the cave, in an isolated point, three human figures are engraved close to each other in a position that has been interpreted as in a dance. The scene seems to want to give particular prominence to the central figure, larger in size than the others, with a face devoid of features and a wedge-shaped head like the anthropomorphic figures in red ochre; long filaments that seem to allude to a beard descend on the chest (P. Graziosi, 1962), while the body missing the arms has a series of short continuous notches that follow the profile of the figure and end at the height of the belt. To his right is a smaller figure, slightly behind the first, with a head devoid of facial features and a similar headgear; this figure has been interpreted as a female character, due to its sinuous shapes and three lines on the arm that suggest bracelets. The third figure is the smallest, placed to the left of the central character, in a back position with respect to the others, with his arms raised, perhaps depicted in a dance scene; the head is in profile, turned towards the central figure, with the face covered by a bird's beak mask (P. Graziosi, 1950).

The headgear of the anthropomorphs of Levanzo has a clear reference to the headgear of the anthropomorph of the Aurignacian levels of Fuman cave In Veneto; it is a fragment of 24×11 cm., painted in red ocher, found together with other overturned fragments at the base of the archaeological level, testifying to the fact that the fragments had detached from the vault or from the walls of the cavity which were therefore painted .

The image represents a human figure with a linear development body, horizontal arms and spread legs, two large horns on the triangular head identified as a mask and two small lateral prominences at the navel; something hangs from the right arm, perhaps a four-legged animal or a ritual object; has been interpreted as a shamanic figure, similar to other figures found at Aurignacian sites, such as the ivory statuette of thelion-man of Hohlenstein-Stadel and the shamanic figure with deer antlers painted in the cave des Trois-Freres in France or like those of the Grotta del Genovese highlighted in the previous image.

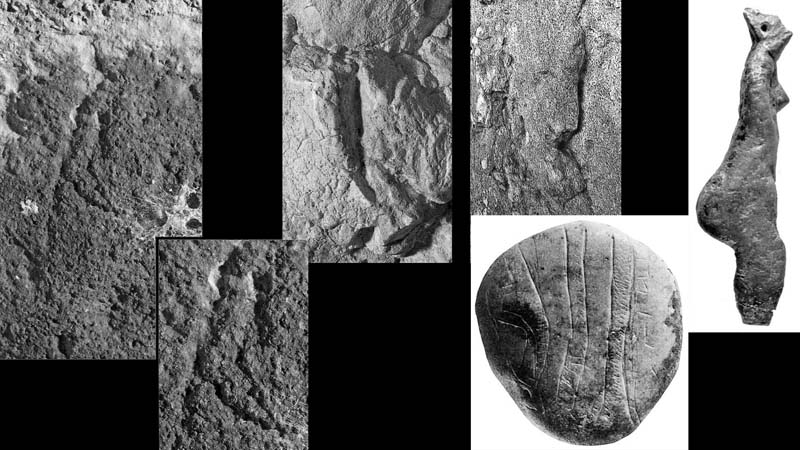

Still on the subject of anthropomorphic figures, the site of Shelter Dalmeri in Trentino Alto Adige, which yielded a total of 220 autochthonous stones painted in red ocher, with dimensions of about 15x10x6 cm., all found on the floor of the cave and dated to about 11.250 BC cal. The stones are painted with different motifs, many with zoomorphic representations, others with schematic symbolic figures, hands, composite figures, different types of stones with traces of red pigment and some stones with anthropomorphic figures. Also in this case, as in the Grotta di Fumane, the stones were found with the decorated face facing downwards, testifying to the fact that the stones detached from the vault or from the painted walls. Studies have made it possible to ascertain that in the most ancient level of occupation of the shelter an area had been delimited where actions of a ritual type were carried out, perhaps initiation ceremonies or places of aggregation on particular occasions or for cult practices (G. Dalmeri and others, 2009).

There are 4 stones with clear anthropomorphic representations, represented in a hieratic posture with an upright trunk, straight and parallel hips, lower limbs widely apart. In particular, the find in the image in the center and the one in the lower left both have a sort of headgear that extends transversely, similar to the headgear of the anthropomorphic from Grotta Fumane or Grotta di Levanzo; in both cases it could be a male image, but it cannot be excluded that it is female, perhaps in the position of giving birth or with a posture during a ritual or a dance. The anthropomorphic in the top left image is represented as if he were in motion during a dance, while the top right image is in a hieratic position with his head in a circular shape, perhaps surmounted by a sort of headgear. The anthropomorphic at the bottom right is of a schematic type, but in general it repeats the same symbols of the previous stones, ie hieratic posture, erect trunk, legs apart and headdress.

Gravettian and Epigravettian female figurines

In Italy we have the highest concentration in Western Europe of statuettes from the Gravettian period, about twenty found in some sites between caves and open-air places, of which more than half found in the Balzi Rossi caves in Liguria, between Barma Grande and the Prince's Cave.

In particular, the first two Italian statuettes were found in the Balzi Rossi in 1883, the one in yellow steatite called the "Yellow Venus"[3] and the one called the "Lady with goiter”, both found in a period in which throughout Europe people began to speak, often in an incredulous way, of Paleolithic art following the discovery in 1879 of the paintings of the Cave of Altamira in Spain. For this reason their discovery was hidden for over a decade, until the discovery in France of the so-called Venus of Brassempouy by Edouard Piette[4] in 1892 and the discovery in 1894, again in Brassempouy, of two further statuettes, l'Ebauche and la Poire, which finally led to the recognition of the existence of these female statuettes dated to the Gravettian.

The Italian figurines lend themselves to iconographic comparisons with many figurines found in the rest of Europe, even in areas very distant from Italy itself.

In the image above, starting from the left we have the Venus of Lespugue (found in 1922 in a quarry near Lespugue, at the foot of the Pyrenees, dated 25.000 years ago), the Yellow Venus (found in the Barma Grande of the Balzi Rossi and dated to around 28.000 years ago), the Venus of Willendorf (dating back to about 23-24.000 years ago, found near Willendorf, in the Wachau region; it has recently been discovered that the rock from which it was made, the oolite, probably comes from Lake Garda, therefore Italian territory, testifying to the large movements of Paleolithic populations), the Venus of Kostienki (found in Russia in 1983, dated to 23-21.000 BC), the Venus of Gagarino (in Ukraine, made from mammoth ivory, dated to about 28.000 BC), the Double Venus of Avdeevo (enigmatic as it is composed of two joined figures, one opposite the other, found in 1941 in Russia and dated to 22.500 years ago). In all these statuettes we can find very similar characteristics, a small head with a smooth face leaning forward, on a distinct neck and narrow shoulders; breasts forming a single mass with the abdomen, flat buttocks, legs tapering downwards, sometimes small arms folded on the belly under the breast (M. Mussi, 2010-2011).

Moving on to the details that are repeated in the various statuettes, the hood is interesting, made up of a sort of triangular appendage that develops from the neck to the shoulders, visible in the Venus of Bracciano (discovered in 2000 in the Marmot Village and probably erroneously dated to the Neolithic period due to the context of the discovery, despite the fact that the features of the statuette suggest the Palaeolithic period), in Venus of Laussel (carved in bas-relief at the entrance to the Laussel Cave in the Dordogne, dated to around 20.000 years ago), on the figure engraved in the Cussac cave (discovered in 2000 in the Dordogne), a feature also present in the Yellow Venus of the Balzi Rossi (M. Mussi, 2010-2011).

Still speaking of hoods, even if different from the previous ones, on the left the two statuettes of Grotto of Venus in Parabita and in the center the statue of Alimini found in a secondary location near Lake Alimini in the province of Lecce: the faces of the Paleolithic statuettes are always covered, leaving no details visible.

In the case of Parrano figurine In Umbria the head is wrapped in a hat while some incisions on the face mark the eyes, nose and mouth; a swollen belly seems to guard a fetus and below it a symbol in the shape of a "V" indicates the vulva represented at the moment of childbirth. A particular detail are the frog-shaped legs that refer to the green stone statuettes depicting the goddess of childbirth in the shape of a frog, indicated by Marija Gimbutas with a regenerative symbolism deriving from their aquatic environment[5] (M. Gimbutas, 2005). Returning to Puglia, a region with many examples of Paleolithic art, again Romanelli cave e Paglicci cave they reference more recent Paleolithic art from northern Europe, especially the female silhouettes of type Gonnersdorf-Lalinde, spread in about 40 sites ranging from the Cantabrian region to Northern France, in Austria, Germany and Poland, in association with Magdalenian or more rarely Azilian industries. The numerous variants are dated to a period between 11.000 and 12.800 years ago (in uncalibrated dating) and the Italian examples are all enclosed in this chronological arc which is part of the Epigravettian period.

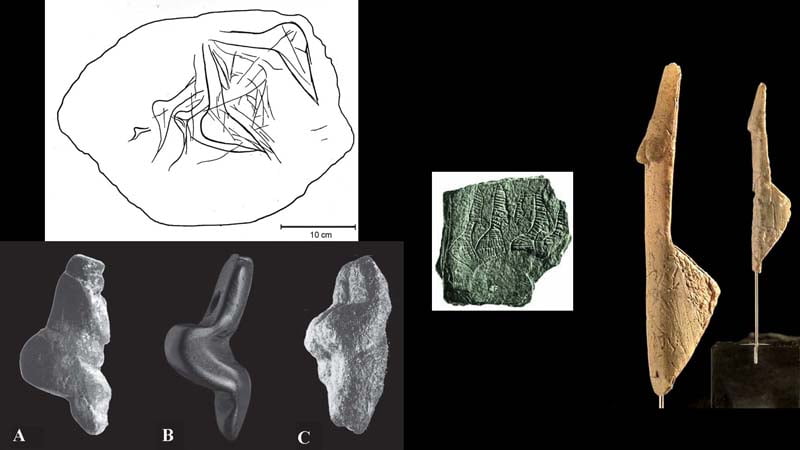

In the image above, at the top left is the blockade of Lalinde in France southwestern, engraved with stylized female figures, with the upper part open and the lower closed pointed, without arms with sometimes a hint of breasts; bottom left three examples of female figurines, from France with the Venus of Courbet (25 mm high), from Switzerland with the pendant of Neuchatel-Monruz (16 mm high) and always from France with the Venus of Enval (31mm high); in the center engraved on the slate plate always the same stylized shape from the site of Gonnersdorf in West Germany and on the right a statue in the round, with the buttocks in prominence and the prominent breasts, always from Gonnersdorf.

Let's move on to Italy, in the image above on the left a small incision of 2 cm. on the wall of Romanelli cave in the southeast of Puglia, dated to about 10-12.000 years ago (uncalibrated dating), recalls the well-known shapes throughout Europe, with the profile inclined towards the front, headless and with well-marked buttocks. The engraving at the top center portrays two silhouettes engraved on the walls of Pit Cave Abruzzo, in an area of central Italy dated to 12-13.000 years ago (uncalibrated dating), with the silhouette obtained by modifying a natural rock edge. Top right the Macomer figurine in Sardinia, just over 13 cm high, made on volcanic rock, discovered in a small cave in 1949 without scientific control, which is why the statuette is not dated precisely, but its characteristics suggest a Paleolithic dating. The head has been interpreted as that of a Sardinian Prolago (M. Mussi, 2009), an extinct lagomorphic mammal, endemic to the Late Pleistocene of Sardinia; the presence of the head is a different feature from the classical Gonnersdorf-Lalinde style, but the general shape typically evokes this style, with legs bent under prominent buttocks, a small, flat torso without arms but with breasts. Below a pebble engraved by Paglicci cave in Puglia, in which three main figures are represented, of which the one on the left has been interpreted as the well-known Gonnersdorf silhouette, with the typical expansion of the buttocks and the legs ending in a point; the other two figures are extremely schematic filled with chevron motifs. Other details compare two figurines from the Balzi Rossi in Liguria with as many figurines from the site of Mal'ta in Siberia; these two sites are thousands of kilometers apart and yet they have elements in common that cannot be the result of fortuitous convergences.

In particular, in the image on the left, a first comparison can be made between the named steatite statuette Lozenge, coming from the Balzi Rossi and the Mal'ta figurine in Siberia. The lower part of the body of the Lozenge, beyond the circular belly, is composed of two V-shaped swellings that frame the pubis where the vulva is incised in a vertical position. This same V-shaped element is present in the Mal'ta figurine, even if the rest of the body is very different. In fact, the bust has flat breasts, the rounded head with the smooth face in an upright position framed by a sort of cap.

The detail of the head is found in another ivory statuette also coming from the Balzi Rossi, the Ocher Checkers and one always coming from With his, also in ivory. The proportions are identical, as is the smooth, upright, slightly rounded face surrounded by a mass of hair and the identical detail of the elongated, wavy curls. What is striking about these two examples are the similarities over long distances, also demonstrated by the movement of raw materials; the differences in the natural environment ranging from the glacial steppes to those of the Mediterranean coasts do not seem to negatively influence the diffusion of common models, symbols, myths and beliefs.

Female burials

The map below shows the places of discovery in Italy and in Europe of some of the female burials of the Gravettian era, the Palaeolithic culture widespread from 29.000 to 20.000 years ago, an era to which most of the more famous statues mentioned above belong.

Il "principleby Arena Candide, woman of Caviglione, woman of Paglicci, finally Delia, the mother of Ostuni.

The map also shows the burial called "the Magdalenian girl" found in France in the prehistoric refuge of cap blanc in which sculptures of animals (mostly horses) dating back to the Magdalenian period, between 18-17.000 and 11-10.000 years ago, i.e. towards the end of the last glaciation, have also been found. Cap Blanc is one of fifteen prehistoric sites and decorated caves in the Vézère valley.

The relationship between these burials is for the grave goods and objects found in them; the care with which the body was buried, the ritual use of red ochre, the presence of almost identical objects, such as the cap made with the same type of shell (with the exception of Paglicci in which a sort of diadem of deer canines), the jewels made with perforated and often engraved deer canines, the lithic objects and finally the morphology of the places chosen for the burials make these finds evidence of the same culture present in Europe for a very long period of time and in which the Italian territory was not differentiated at all, despite the Alpine barrier.

This culture used certain symbols, such as the shell headdress (a detail that brings us back to the statuettes of Willendorf in Austria or Brassempouy in France, just to name a few), or like red ocher, another typical symbol of coeval funerary rituals, represent the color of the blood that regenerated the newly buried body.

The burial of the Prince of Arene Candide, a burial that in terms of notoriety has gone beyond the Italian borders, is the only one that at the current state of investigations is attributed to a young man of about 15 years of age, robust and about 170 cm tall. , buried after a violent death probably caused by the attack of a bear during a hunting trip, with a blow to the jaw and left shoulder which in fact have been removed. It was discovered in 1942, dated to 26.300 BC, placed on a bed of red ocher, with a rich funerary outfit consisting of a headgear made up of hundreds of perforated shells and deer canines, mammoth ivory pendants, 4 pierced sticks 'moose, three of which are decorated with fine streaks and a flint blade of 23 cm. held in the right hand. A DNA investigation has never been carried out on the bones but only an analysis that led to establishing their sex, which for an adolescent skeleton is not immediate to guarantee the correct attribution, therefore it cannot be said with absolute certainty that it is a male skeleton and, if this were ascertained following DNA analysis, he would be the first man to be buried with a kit typical of female burials, such as the headdress made of shells and red ocher scattered on the burial surface. On the other hand, a memorable precedent was the story of the "Donna di Caviglione" of the Balzi Rossi, identified for many years as belonging to a male skeleton, known as the "Man of Menton" and only after a DNA investigation was it possible to ascertain with certainty that the skeleton was that of a woman.

The diet of the Paleolithic

A final curiosity is related to the diet of the Paleolithic people. In Tuscany, exactly in the locality Bilancino in Mugello, among the thousands of Paleolithic artifacts found in the excavation, a mill with an attached pestle was discovered; the peculiarity is that these instruments preserved traces of starch dating back to about 30.000 years ago visible under the microscope and at carbon 14. This discovery was further strengthened by the discovery inside Paglicci cave in Puglia of a 33.000-year-old pestle, therefore older than the Bilancino millstone, on which traces of starches from various wild plants were found, especially oats. Studies have shown that the Paleolithic of Grotta Paglicci had developed some technologies for processing the plant before grinding; in fact, traces of thermal pre-treatment have been found (it is not known whether with boiling, toasting or roasting) in order to facilitate grinding, thus facilitating the discarding of the external coating of the grains and guaranteeing a greater shelf life of the flour.

"The implications of this discovery are in many ways revolutionary”, underline Biancamaria Aranguren of the Archaeological Superintendency of Tuscany and Anna Revedin of the Italian Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory, “… For the first time man had at his disposal an easily storable and transportable elaborated product, with a high energy content because it was rich in complex carbohydrates, which allowed greater autonomy especially in critical moments from a climatic and environmental point of view. The discovery also demonstrates that the technical ability necessary for the production of flour and therefore for preparing food, biscuits or porridge, was already acquired in Tuscany long before the birth of agriculture in the Neolithic, linked to cereals, which developed in Middle East…".

Elvira Visciola, November-December 2022

Footnotes

[1]“…Luigi Pigorini intervened directly or indirectly, through members of his circle, to suffocate or discredit in an extremely decisive way news relating to finds attributable to Paleolithic art, both movable and wall art. This happened starting from 1884 when an attempt was made to remove news relating to the Venus of Tolentino from the scientific circuit; and again from 1904 with the rejection of the presence in the Romanelli cave of the Upper Paleolithic and of any artistic expression associated with it. This position will still have aftermath after his death, with the controversy initiated by Ugo Antonielli, his successor as director of the prehistoric museum in Rome, who wanted to demonstrate that the Venus of Savignano was to be attributed to the Neolithic. After more than a century, the impact of these positions in delaying the development of research must be evaluated..." (M. Mussi - "Luigi Pigorini and paleolithic art in Italy" - in XLVI Scientific Meeting of the Italian Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory – Rome 2011).

[2]The last colony of great auks was attested on an island off the coast of Iceland where in 1835 there were about 50 specimens and the last pair was killed while incubating an egg on June 3, 1844, at the request of a merchant looking for of specimens for the museum.

[3]The statuette is also the logo of the Prehistory in Italy site.

[4]A magistrate collector of prehistoric art.

[5]"… Human life begins in the watery realm of a woman's womb, so by analogy the goddess was the source of all life, human, plant and animal. It reigned over all sources of water: lakes, rivers, springs, wells and rain clouds… The habitat of these beings constituted an analogy with the amniotic fluid, that uterine watery realm where regeneration takes place… Art neolithic fashioned thousands of female-frog hybrids. At many Neolithic sites, craftsmen carved small frog goddesses out of green or black stone and placed them in relief on vessels or temple walls. The presence of the divine vulva accentuates the regenerative force of these images… The image of the frog and the toad, together with the woman in the form of a frog showing her vulva, spread over a wide period of time and not only in the European Neolithic and Anatolian, but also in the Middle East, in China and in the Americas… The conception of this image can even be traced back to the upper Paleolithic, since bones engraved with frog-women appear in the Magdalenian era… The dynamic persistence of the toad-goddess provides the explanation for a quite mysterious historical image: the “unchaste” Sheela na gig which appears on stone buildings in England, France, Ireland and Wales, seated, naked, with her frog legs spread wide, and with her hands on the vulva. These figures were carved on castles and churches between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries. They can usually be seen on the entrance arches or on the walls of churches. Both hands of the Sheela na gig point to her genital area or hold her lips apart. Some sculptures feature scary faces or even skeleton skulls. Sheela na gig is still highly revered, but her presence, of course, is shrouded in mystery. She can only be the descendant of the ancient frog-goddess, the great regenerator…” (Marija Gimbutas – The living goddesses – Medusa 2005).

REFERENCES

- Margherita Mussi – “Luigi Pigorini and Paleolithic art in Italy” – in the XLVI Scientific Meeting of the Italian Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory – Rome 2011;

- Dario Sigari, Ilaria Mazzini, Jacopo Conti, Luca Forti, Giuseppe Lembo, Beniamino Mecozzi, Brunella Muttillo and Raffaele Sardella – “Birds and Bovids: new parietal engravings at the Romanelli Cave, Apulia” - In Antiquity – Publications vol. 95, number 383, October 2021;

- Franco Mezzena and Arturo Palma of Cesnola – “New manifestations of Epigravettian art of the Paglicci Cave in the Gargano" - In Proceedings of the XXVIII Scientific Meeting of the Italian Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory – Florence 1989 – pp. 277-292;

- Arturo Palma of Cesnola – Clowns Rignano Garganico – Puglia Region, 1988;

- Francesco Zorzi – “Wall paintings and movable art objects from the Paleolithic discovered in the Paglicci cave near Rignano Garganico” - In Journal of Prehistoric Sciences – XVII 1962 – pp. 123-137;

- Dean R. Snow – Sexual dimorphism in Upper Palaeolithic hand stencils – Antiquities – vol. 80 – pp. 390-404 - 2006;

- Dario Cigars – “Review of the animal figures in the Palaeolithic rock art of the Romito Shelter. New discoveries, new data and new perspectives” – in Oxford Journal of Archeology – September 2020;

- Jole Marconi Bovio – “Interpretation of the wall art of the Addaura” - in Bart booklet –1953;

- Maria Laura Leone The Phosphenic Deer Cave. Art, Mythology and Religion of the Painters of Porto Badisco – Ed. Prehistoric Thought – 2009;

- Giuseppe Bolzoni – “New observations on the engravings of the Grotta Addaura of Monte Pellegrino (Palermo)" - In Proceedings of the Tuscan Society of Natural Sciences – Series A – 92 (1985) p. 321-329;

- John Mannino - "The prehistoric wall graffiti of the Addaura Cave: the discovery and new acquisitions” - In Proceedings of the XLI Scientific Meeting – San Cipirello (PA) 16-19 November 2006 – Florence 2012 – pp. 415-422;

- Paolo Graziosi – Levanzo, paintings and engravings – Florence 1962;

- Francesca Minellono – “Annotations on two-dimensional anthropomorphic images of the Italian Paleolithic” – in Journal of Prehistoric Sciences – XLIX 1998 – pp. 83-101;

- Sebastiano Tusa (edited by) – First Sicily. At the origins of Sicilian society – Ediprint 1997;

- Fabio Martini – “The visual culture of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic in Italy. Themes, iconographic languages, formal aspects” - In Alpine prehistory - no. 46 I (2012) - Trento 2012 - pp. 17-30;

- Alberto Broglio – “The pictorial decoration of the Grotta di Fumane” - In Historical Yearbook of Valpolicella 11-32 - 2010-2011;

- Alberto Broglio, Mirco De Stefani and Fabio Gurioli – “Aurignacian paintings in the Grotta di Fumane” - In Proceedings of the Veneto Institute of Sciences, Letters and Arts – Volume CLXII – 2003;

- Giampaolo Dalmeri and Stefano Neri – “Riparo Dalmeri: the man and two styles of representation. Formal analysis of four stones decorated with anthropomorphic figures” – in Alpine prehistory - 43 - 2008 - pp. 299-315;

- Giampaolo Dalmeri, Anna Cusinato, Klaus Kompatscher, Maria Hrozny Kompatscher, Michele Bassetti and Stefano Neri – “The ocher painted stones from the Riparo Dalmeri (Trento). Development of the research on the art and rituality of the Epigravettian site” – in Alpine prehistory - 44 - 2009 - pp. 95-119;

- Margherita Mussi – “Les “Venus” du Gravettien et de l'Epigravettien italien in a European cadre” – in Jean Clottes – L'art pléistocène dans le monde / Pleistocene art of the world / Pleistocene art in the world – Actes du Congrès IFRAO – Tarascon-sur-Ariège – September 2010 – Symposium «Art pléistocène en Europe» – N° spécial de Préhistoire, Art et Sociétés, Bulletin de la Société Préhistorique Ariège-Pyrénées, LXV-LXVI, 2010-2011;

- Marija Gimbutas – The living goddesses – Medusa 2005;

- Margherita Mussi, Pierre Bolduc and Jacques Cinq-Mars – “Les figurines des Balzi Rossi (Italy): a perdue and retrouvée collection” - In Bull. Société Prehistorique de l'Ariège –1996;

- Margherita Mussi, Pierre Bolduc and Jacques Cinq-Mars – “The 15 Paleolithic figurines discovered by Louis Alexandre Jullien at the Balzi Rossi” - taken from Origins – Prehistory and Protohistory of Ancient Civilizations –2004;

- Claudine Cohen – The woman of origins – Belin Herscher 2003;

- Margherita Mussi, Paul Bahn, Alessandro De Marco and Roberto Maggi – “New discoveries of Paleolithic wall art in Italy: the Cave of Arene Candide and Grotta Romanelli" - In Alpine prehistory – no. 46 - Trento 2012;

- Margherita Mussi and Alessandro De Marco – “A Gonnersdorf-style engraving in the parietal art of Grotta Romanelli (Apulia, southern Italy)” – in Mitteilungen der Gesellschaft fur Urgeschichte – no. 17 - 2008;

- Margherita Mussi – “Grotta di Pozzo (AQ, central Italy), a cave ornèe 'au feminin'” - In Pleistocene art in the world – edited by Jean Clottes – Actes du Congres IFRAO – Tarascon sur Ariege – 2012 – pp. 1783-1792;

- Margherita Mussi – “A female silhouette in the Paleolithic wall art of Grotta di Pozzo (AQ)” – in Fucino and the neighboring areas in Antiquity – IV Archeology Conference – 2016 – pp. 59-64;

- Margherita Mussi – “The Venus of Macomer, a little-known Sardinian prehistoric statuette" – in Paul Bahn Ed. – An inquiring mind. Essays in honor of Alexander Marshack – American School of Prehistoric Research – Harvard University – pp. 193-210 - 2009;

- Margherita Mussi – “The “Venus of Macomer” and Paleolithic iconography” – in Manfredo Atzori (edited by) – Studies in honor of Ercole Contu – pp. 29-44 – Sassari 2003;

- Donato Coppola – The Shelter of Agnano in the Upper Paleolithic – The burial of Ostuni 1 and its symbols – University of Rome Tor Vergata – 2012;

- Anna Revedin, Laura Longo, Marta Mariotti Lippi, Emanuele Marconi, Annamaria Ronchitelli, Jiri Svoboda, Eva Anichini, Matilde Gennai and Biancamaria Aranguren – “New technologies for plant food processing in the Gravettian” – in Quaternary International – XXX – 2014;

- Biancamaria Aranguren and Anna Revedin – 30.000 makes the first flour. At the origins of nutrition – Florence 2015.