di Valentina Mauriello

Castelvetro is a small town located on the first hills of the Modenese Apennines, straddling the Guerro torrent, a tributary of the Panaro river, famous for the beauty of the historic village and for the food and wine offer of typical Emilian products, among which Lambrusco and Balsamic Vinegar stand out . The surrounding land is teeming with vineyards of great value. The entire foothills and therefore also Castelvetro, is rich in archaeological evidence that attests to the attendance of these areas since the Paleolithic. And the territory was an important transit route towards the Modena plain.

In 1841 Wenceslao Vandelli, the owner of land located on the left bank of the Guerro, found 4 Etruscan tombs during the excavation for the planting of trees. Excavations resumed only decades later, in 1879 when his son Nicola Vandelli carried out a further excavation with the dual purpose of looking for new tombs and transforming the farm into a vineyard. 31 sepulchres emerged from the excavation. The fact that the initial excavations were carried out by the owners of the land and that the land is irreparably compromised from an archaeological point of view, led to a great deal of subsequent reconstruction work of what must have been the original physiognomy of the burial ground starting from documents of archive and from the analysis of the finds. This twenty-year study by Donato Labate (scientific collaborator of the Museum under the direction of Andrea Cardarelli and more recently on behalf of the Archaeological Superintendence) analyzed notes and transcripts of the two archaeologists who first began research on the site at the end of the nineteenth century and recovered the rich funerary objects that are now exhibited in the Civic Museum of Modena: Celestino Cavedoni (1795 -1865) and Arsenio Crespellani (1828 -1900). The Etruscan burial ground of Galassina is part of an area rich in Etruscan testimonies referable to two phases of attendance, the first datable to an older era, Villanovan IV, the second between the first half and the end of the XNUMXth century BC

Among the material described by Crespellani coming from the excavations carried out between 1879 and 1880 by the owners of the land appears the mention of an object "a sandstone stone in the shape of…” which was recovered together with other scattered objects following the excavation. This particular pebble was deposited in the deposit of the Civic Archaeological and Ethnological Museum of Modena in a box together with other finds. A description compatible with the object in question appears in a nineteenth-century inventory of the museum: "sandstone pebble in the shape of a pendant with graffiti".

This pebble, decorated with fine incisions, is particularly significant as it depicts a highly stylized female character with sexual attributes rendered by three cup marks. It was found in the museum archive by Benedetto Benedetti (professor, director of the Archaeological Museum of Modena and of the magazine "Emilia preromana") and described it in the book "Prehistory and Protohistory of Modena" published in 1987 by a publishing house in Bologna as l 'idol of Galassina.

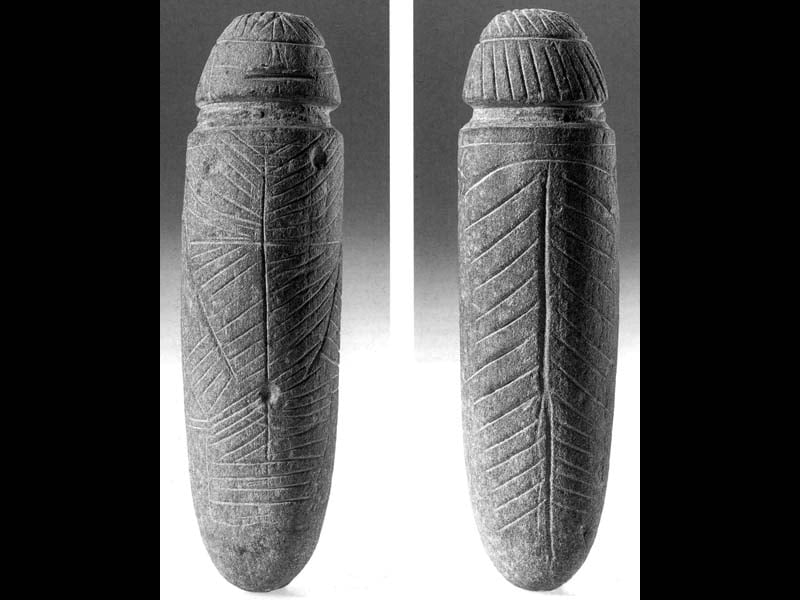

"It is a pebble of fine-grained gray sandstone shaped by the fluvial flow into an oblong shape with rounded ends (phallic shape), with a slightly arched longitudinal axis and an ellipsoidal cross-section. The head separated from the trunk by an incised furrow is decorated with incisions that seem to represent well-formed hair and surrounded at the top by a cord; the face is broad and flattened, the front of the body is covered by a plot of oblique lines that could represent a tunic; three cup marks, located at the vertices of an ideal inverted triangle, indicate the breasts and the sex; from the shoulder, rendered with an engraved triangle, the arms descend at the end of which a regular rectangle divided by two parallel lines represents the hand and the five fingers. On the back, the herringbone design seems to take up the motif of the tunic, albeit with a different form. It cannot be denied that the pebble – support of the engraving – clearly expresses, on its own, a phallic form".

The interesting find was studied at the Institute of Petrography of the University of Modena by Professor Mario Bertolani. The find was covered by a calcareous crust (calcium carbonate) which almost completely hid the incisions and was probably cleaned by non-experts. By analyzing what remained of the calcareous crust, Professor Bertolani confirmed its antiquity with certainty. The professor also found green spots on the incrustation attributable to alterations due to copper or bronze.

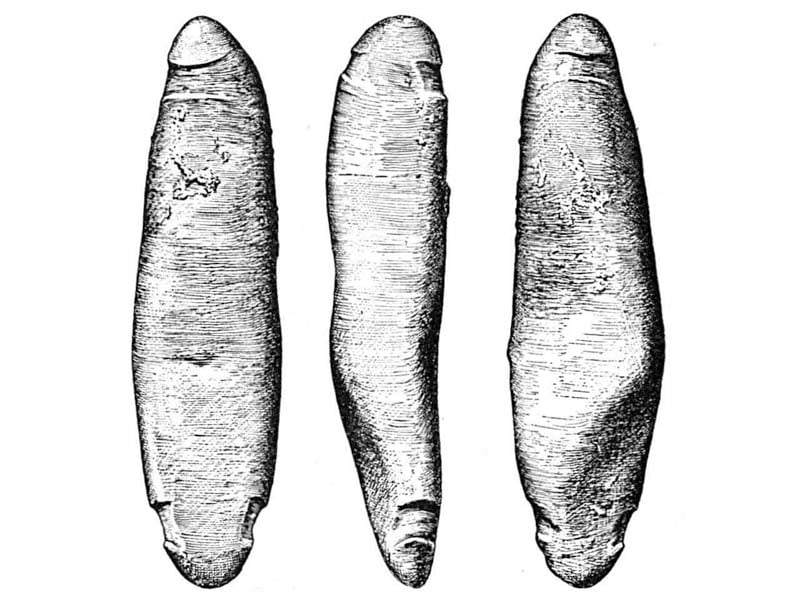

Benedetti believed that this find belonged to the Eneolithic period (end of the Neolithic beginning of the Copper Age) based on stylistic considerations, comparisons with Eneolithic idols in the Danube area, combinations with the art of stele, with Camunian rock art, with very similar pebbles from the Eneolithic and Early Bronze station of Busone in Sicily. There is one find in particular from the Eneolithic necropolis of Laterza published by Franco Belfiore which has a shape and type of engraving very similar to the idol in question.

It is interesting to report two considerations expressed by Benedetti in the text "Stones and Words, places and traditions of the Modena area" by Benedetto Benedetti and Franco Violi, which can be related to the idol of Galassina. The first concerns the discovery in Fiorano (Carani furnaces) in the Modena area of a sandstone pebble found in the bottom of a hut during the excavation of one of the most important Neolithic settlements in the Modena area and dated with certainty to the XNUMXth millennium BC which has a tapered shape from the fluvial flow (which if observed from a particular angle could resemble a schematic female human body) and which presents sure signs of workmanship: two transversal furrows at the two ends, one of these may suggest a sketch of the head.

Two scholars discussed the interpretations of this find, Ferdinando Malavolti and Paolo Graziosi, bringing out three hypotheses:

- it is an artifact whose function is unknown;

- it is a sketched or unfinished sculpture;

- it is a female figurine of schematic style.

In the latter case, the dating would be known with certainty and it would not be a common fact, since many female statuettes that emerged in the last century were not found within the layer, therefore it is difficult to have a precise idea of their temporal location.

The second interesting consideration expressed by Benedetti is related to the description performed by Arsenio Crespellani of the grave goods relating to the excavation of the Etruscan necropolis of Galassina carried out by his son Nicola Vandelli. In this description, the presence of diluvial and quartzite pebbles mixed with the grave goods and still preserved in the Archaeological Museum is repeatedly noted. They could give a further cultic meaning to the discovery of the controversial little idol inside the tombs.

The presence of the idol inside the Etruscan necropolis can have various interpretations:

- the erratic pebble attracted the attention of an ancient finder in the Etruscan age who collected it and placed it in the grave pit together with the rest of the grave goods made up of bronzes and ceramics;

- the pebble was in the ground and ended up in the filling of the pit during the inhumation at the time of the Etruscans together with other pebbles;

- the pebble lay in a layer whose existence was not noticed as the excavation was carried out with spades by the farm laborers and not by specialized archaeologists;

- the pebble was removed from its present location during the first recoveries of 1841 or by clandestine excavators who subsequently stripped the tombs of the burial ground;

- the pebble was transported to the Galassina farm together with the soil from one of the "terramare" or Bronze Age settlements present nearby. In fact, it was a widespread practice in the 800th century to fertilize the fields with fertilizing soil from quarries such as that of Monte Barello where there are attestations from the Neolithic period that can potentially be connected with the idol in question (D. Labate 2006, p.33).

The idol at the Civic Ethnological Museum of Modena was subjected to subsequent examinations commissioned by archaeologists specialized in traces of use. These have determined that the engravings on the pebble were produced by pointed metal objects and therefore not attributable to an ancient age. The lack of patina (chemical alteration of the surface with deposits created by permanence in the ground) which is normally created in the case of antique objects would also be problematic. At the physical-chemical examination performed at the University of Modena by prof. Mario Bertolani at the time of Benedetti the pebble appeared to have already undergone a deep cleaning process and given the scarcity of material, it is no longer possible to perform further analyzes today.

Despite the uniqueness of the find, the data emerging from the analyses, the exclusion by prof. Benedetti that it could be a recent forgery and the various plausible hypotheses, the position of the Civic Museum and the Superintendency is of doubt as to the authenticity of the find due to the impossibility of confirming its dating with certainty. For this reason it is not exhibited.

The perplexity of the writer is this: what is the point of inserting a sandstone pebble engraved with rather peculiar stylistic characteristics among the finds of the excavations carried out at the end of the nineteenth century if it were not that the pebble was actually found in situ? Even if the engraving was done in the Copper or Bronze Age, would that make the figurine less significant? Does the fact that the pebble was engraved with metal points necessarily make it a fake?

Who knows if the Galassina statuette will be recognized in the future as one of the Italian "Venus" expression of our ancestral spiritual roots or will remain buried in the archives and forgotten.

Valentina Mauriello, February 26, 2023

REFERENCES

- Chiara Pizzirani – “The Etruscan burial ground of Galassina di Castelvetro (MO). Preliminary analysis of topographic data and tomb contexts” – in Pre-Roman archeology in Western Emilia – Acme notebooks – 108 – 2009 – pp. 165-179;

- Andrea Cardarelli and Luigi Malnati (edited by) – Atlante dei Beni Archeologici della Provincia di Modena – Vol III – Insignia of the Lily – 2003;

- Donato Labate – Castelvetro. Archeology and topographic research – Insignia of the Lily – 2006;

- Franco Biancofiore – “The Eneolithic Necropolis of Laterza. Origins and developments of the Proto-Apennine groups in Apulia” – in Origini – Rome 1967 – pp. 195-300;

- Benedetto Benedetti and Franco Violi – Stones and Words, places and traditions of the Modena area – Emilio Ballestri Publisher – Vignola – 1992;

- Fernando Malavolti – “A problematic lithic artefact from the Aeneolithic station of Fiorano Modenese” – in Journal of Prehistoric Sciences – file 1-2 – 1946 – pp. 113-118.