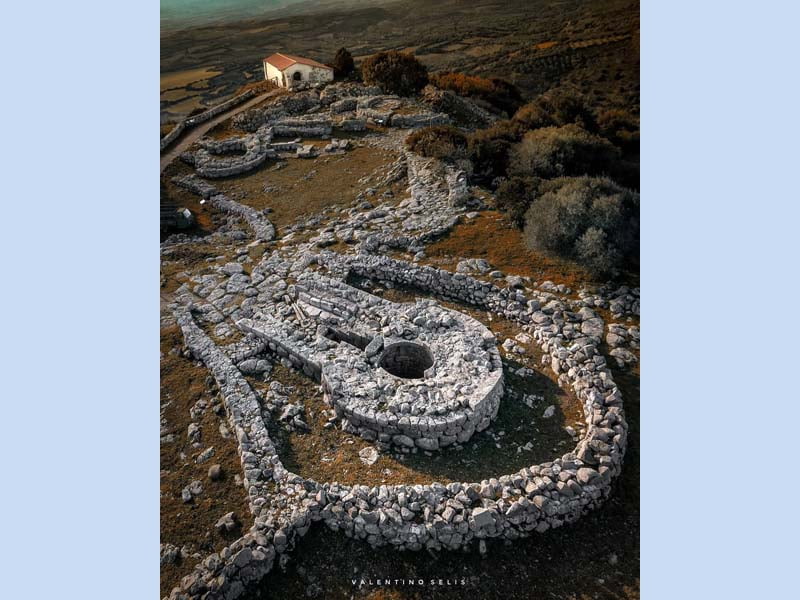

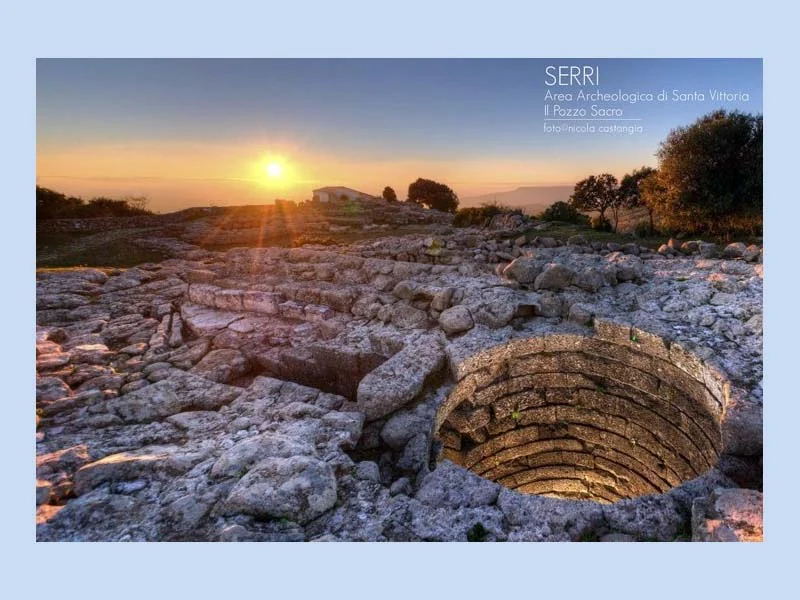

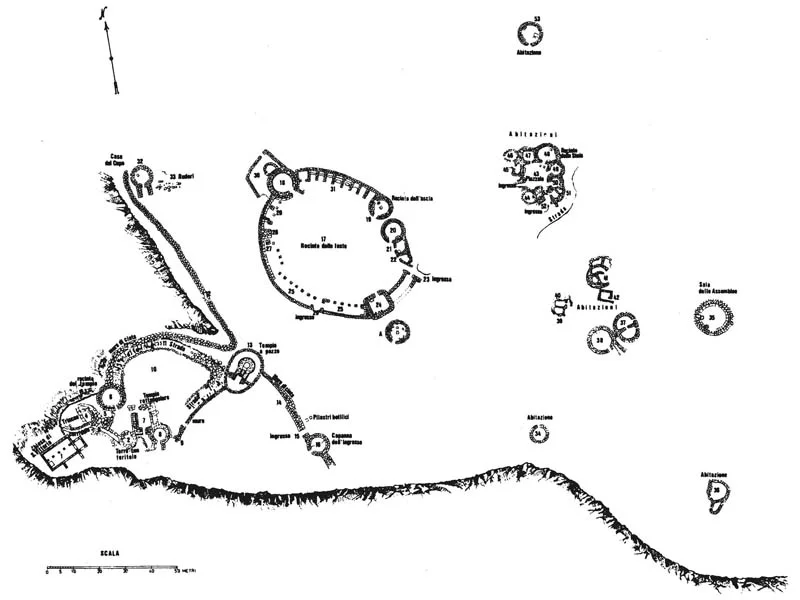

The sacred well of Santa Vittoria is located within one of the most important cultural complexes of nuragic Sardinia which houses various structures, including housing, and is located in the Serri area, Sardinia. The archaeological site, built during the Bronze Age, has ample traces of attendance in the following centuries and takes its name from the church dedicated to the martyr Santa Vittoria, whose feast day is celebrated on 11 September.

The site, which covers an area of about 22 hectares, is configured with:

- the holy well/well temple

- a protonuraghe, later incorporated into a tholos nuraghe

- two temples in antis, one called the "hut or house of the priest" and the other the "hut or house of the chief"

- a hypetral temple (without cover)

- the so-called "via sacra" which connects the well temple with the hypetral temple, and is 50 meters long and 3-4 meters wide

- a meeting hut or “Curia”

- an enclosure to celebrate the holidays

- several residential huts

The first find found dates back to the early Bronze Age: a tripod vase and a burial with a jadeite ax and a small copper dagger, found in the so-called "capanna del capo".

Excavations have shown that the buildings suffered violent destruction during the Roman period by fire.

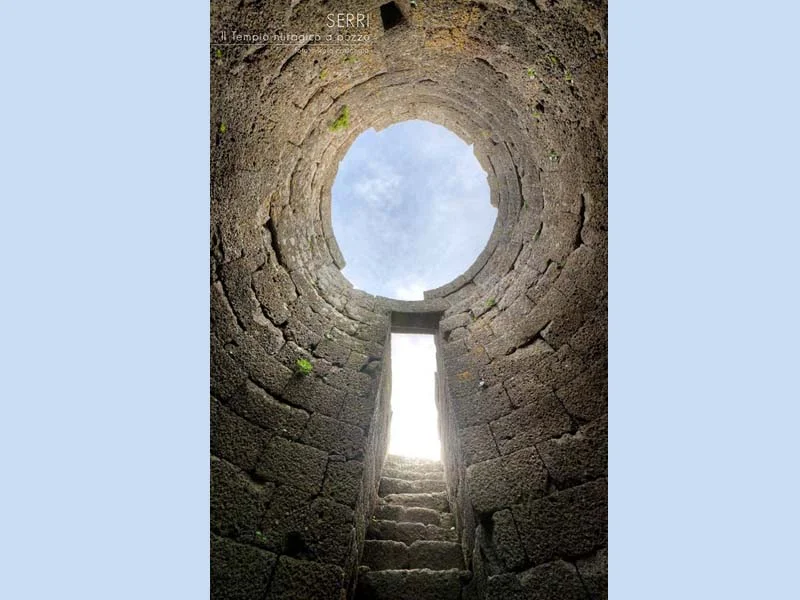

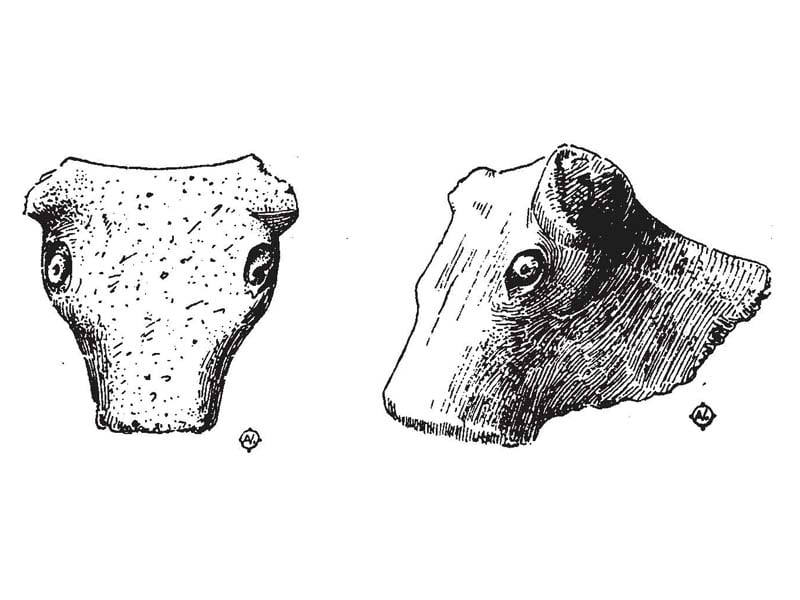

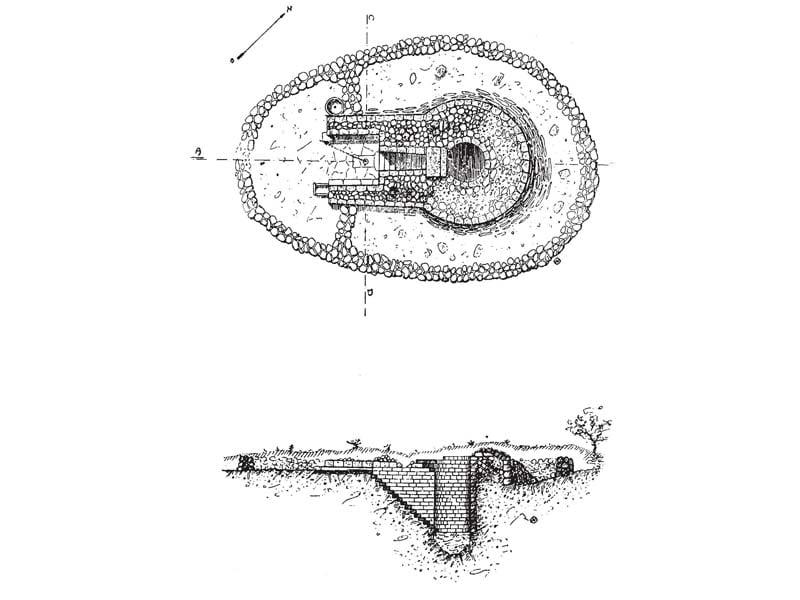

Il sacred well, in which a series of vases were found, seems to belong to the recent Bronze Age, while several votive bronzes belong to the Iron Age, testifying to the cults that must have taken place inside the sanctuary, dotted with baetyls. Although the reuse of the site dates back to the Middle Ages, during the Roman and Byzantine periods military occupation was found, as evidenced by the burials and related equipment. The sacred well is enclosed by an elliptical enclosure of basalt rows (19 x 13 m), has a canonical layout of: atrium, staircase and well and is NE/SW oriented. The atrium is a square of 2 x 2 meters with a paved floor on which rests a counter-seat and a rectangular altar which has a cavity and drain hole for liquids to flow out. The staircase made up of 13 steps has a stepped roof and enters the cylindrical well (2 meters in diameter) originally surmounted by a tholos roof. It is believed that the frontispiece of the sanctuary was originally decorated with two limestone bull protomes and a dentil frieze. For the important cultural values of well temples, see the article on the site Saint Christina of Paulilatino.

Among the finds the most important are:

- anthropomorphic bronzes (including two female figures holding a male child (?) in their arms and some male bronzes with weapons)

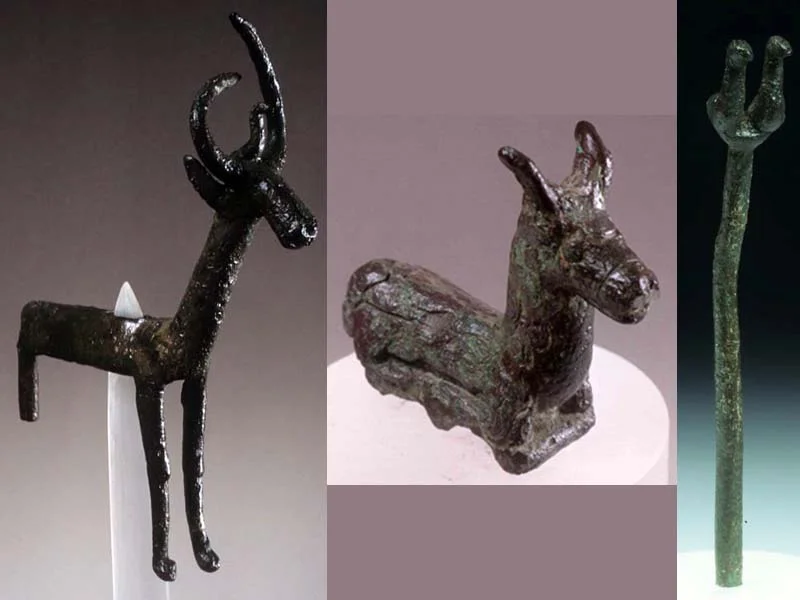

- small bronzes of animals and votive vessels

- nuraghe-altar models

- coins from various eras

- taurine protomes

- rings, bracelets

- ceramic vases

- bronze pottery miniatures

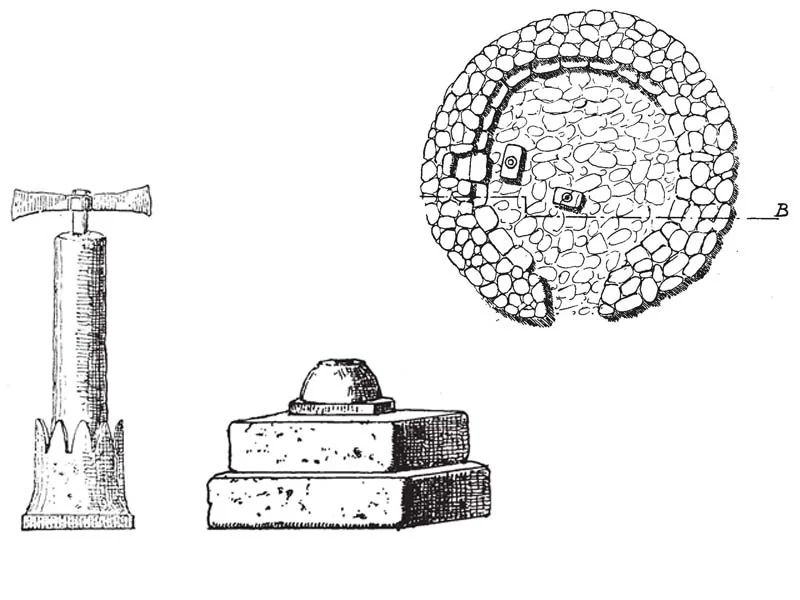

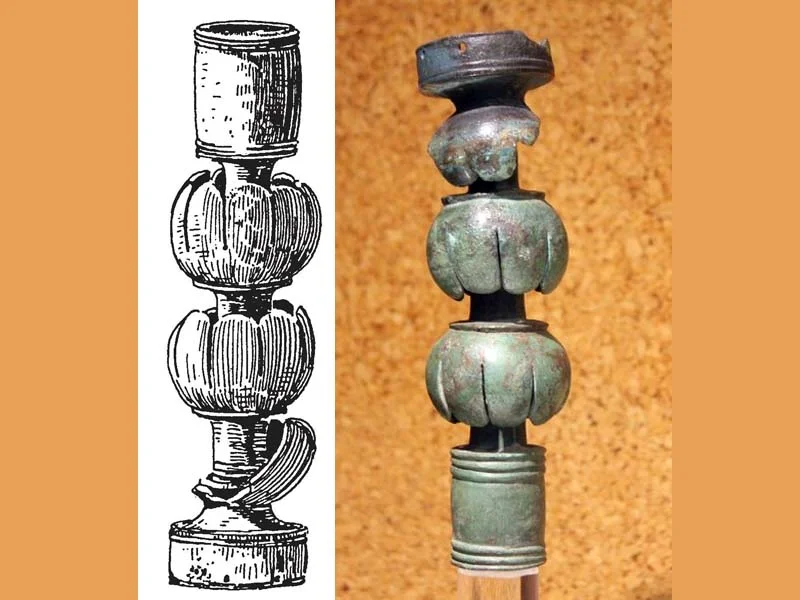

Of notable interest is also the so-called “Hut of the Great Axe” circular in shape with a diameter of 6,95 m. huh: 2 m. which presents the base of an altar and a small pillar with decorations. The hut is located inside the enclosure of the festivities and takes its name from the discovery of the homonymous ax which unfortunately is not visible in any museum and of which we only have the drawing and descriptions by Taramelli. The bronze axe, 27 cm long, was defined by Taramelli as a "sacred bipenne betilica"; according to the scholar it was connected to the monoic cult of labrys. In confirmation of the ceremonies performed, in this building, as in others on the site, abundant remains of ritual meals were found, including bones of sheep, pigs, cattle, game and molluscs (cardium and mytilus).What happened to the great axe? It is difficult to understand how such a significant find disappeared (probably) buried in some museum warehouse. Even more difficult is to understand why there are no academic publications about it. The double axe, both in the materiality of the object and as a symbol, assumes, according to various scholars, a fundamental importance in the cults of the Great Mother in the Minoan sphere; other archaeologists, while recognizing its great importance, indicate it as a symbol of male divinities. Despite these differences, the symbol of the labrys it is so significant that a scholar of the caliber of Martin Nilsson has declared that one cannot understand Minoan-Mycenaean religion without understanding the double axe. In general, it seems that these axes, with a clear symbolic and ritual meaning, were also tools that were actually used during ritual sacrifices. In the palace of Knossos excavations have brought to light several specimens. Through appropriate investigations, the presence of the ax could shed light both on the cults and rituals that took place on the site of Santa Vittoria di Serri, and on the links between the native Sardinian populations and the Minoan-Mycenaean world.

Anthropological side notes: religious syncretism or embezzlement? Various scholars point out how the Church overlapped with pre-Christian cults, derogatively defined as pagan. In Sardinia this phenomenon often occurred within pre-Nuragic (read Neolithic) and Nuragic cult areas such as, for example, sacred wells, but not only. The pre-existing cults and rites, despite the attempted cancellation of the subsequent Christian ceremonies, have shown a strength and persistence such as to survive over the centuries or even millennia. In the case of holy wells of Santa Cristina di Paulilatino, Santa Vittoria di Serri and Santa Anastasia di Sardara, it can be seen how all these structures linked to the cult of water have been flanked by a small country church dedicated to a saint whose cult, curiously, is celebrated during the months of the agro-pastoral season (May to September). As the anthropologist Clara Gallini notes, these are precisely the months in which all the agro-pastoral communities, since ancient times, gathered to celebrate events, sanction marriages, etc. thus celebrating the most important phase of the life cycle. As proof of this, in the Sardinian dialect the month of September, in which we have seen the saint of the Nuragic well is celebrated, takes the name of Cabudanni o New Years (from Lat. caput years), the beginning of the year.

Archeology and folklore: about popular traditions, archaeological finds and labrys, in Sardinia, I would like to mention an interesting oral document, transcribed by Francesco Enna in his essay entitled Sos contos de fogile (in Italian: tales from the hearth). This scholar, also taken up by Dolores Turchi, reports a popular legend told by an old woman from Macomer, Maddalena Deriu. The text presents interesting references to the cult of water, to sacred wells, to the labrys and also to a fairy figure, probably one Jana (the fairies/witches of the house of janas). Here is the text in the Italian translation (my bolds):

“In Macomer, when I was little they told me many stories. I remember one that is in poetry. Maybe it was a song, but I only remember the words. And the legend of Maria Giusta. This is the story of Maria Giusta. She dressed in cloth she went to the cliff, dry wood to look for, wood to heat. A holm oak finds you with silver branches. The rain began, lightning struck. Once the storm stopped, the holm oak was reduced to ashes, the holm oak was to ashes.

From the ax without a handle, one comes out to, to the blow he gave.

È dove her heart, her hair of gold: her hair of gold, the two-wire axe.

“Go find the well which is now dry. The large water well, without bucket or door; without door or bucket, throw us the ax”. She finds that well, large, dry and deep, throws the ax into it, drinks without a bucket, forgets everything. The days go by in droves. The river dried up in the middle of the summer.

Everyone is suffering, they are dying of thirst. She realizes that her son is going limp like a lily. She returns to the well, down to the dry bottom. Dry is the great water, neither bucket nor door, neither door nor bucket, there is no ax. Then she heard a voice, a voice from far away: "Water is not born unless blood feeds it." As soon as you throw it, fresh water gushes out. This is the story of Maria Giusta. For water she killed herself, in the well of the cliff."

Leaving aside the innumerable readings and interpretations of the legend of Maria Giusta, in this article I will limit myself to pointing out the references and connections between the cult of water (with its sacred well) and the feminine sphere in its two main characters: Maria Giusta and the fairy/jana with the golden hair. Characters interacting with the double axe, an instrument sacred to the Minoan-Mycenaean world (but evidently widespread in the Mediterranean area), which seems to guarantee or deny access to water. A further reference seems to be that of ritual sacrifices, so much so that the protagonist, in order to obtain water again, must sacrifice her own life. Water which, as Turchi points out, seems to be that of oblivion in Sardinian "s'abba e' s'irmentigu" (the water of forgetfulness) spoken of in popular traditions in inland towns whose inhabitants would lose memory by drinking in certain sources. These legends resume the Greco-Roman myth of the source of Lethe, related to the myths about reincarnation of souls? It is probable, just as it is possible, that the well mentioned in the ballad could allude to the sacred wells whose cults were celebrated in prehistoric times and whose echo has come down to us through the popular memory of the female line, so much so that the story is a woman. Dolores Turchi, in her investigation of this text, adds further elements that complete a picture with extensive references to the sacred feminine: according to the scholar, in fact, the dove mentioned in the text refers to the divining priestesses of the classical world, in particular of the temple of Dodona who used the double ax in water-related rituals.

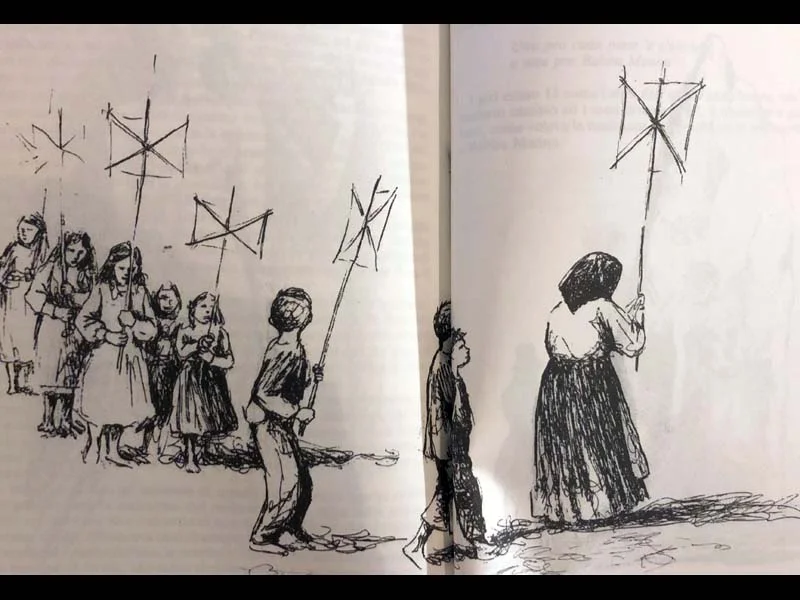

Another element that allows us to hypothesize a link between the pre-Christian cults linked to the double axe, the cult of water and subsequent popular traditions, is the procession that was held in Nuoro to ward off moments of severe drought. According to Turchi, a group of women with children went in procession towards the river carrying in their hands "sas ruchittas" or sticks made of crossed reeds with a shape that seems to recall the double axe. The text of the oral tradition transcribed from Enna and the studies of Turchi thus become a precious source that allows us to connect archaeological finds, folklore and the (often forgotten) history of the sacred female power in an island full of legends and archaeological finds without written sources direct.

Historical notes

The first excavations in the area of Santa Vittoria di Serri were carried out by the archaeologist Antonio Taramelli (accompanied by the historian of religions Raffaele Pettazzoni) and date back to the years 1909-1931. These were followed by other excavation campaigns in the 60s (Contu and Muzzetto) in the 80s/90s (Murru, Campus and Puddu) to end with the excavations of the years from 2007 to 2015 (Fadda, Mancini and Saba).

CARD

LATEST PUBLISHED TEXTS

VISIT THE FACTSHEETS BY OBJECT