Autochthonous civilizations lit up along the coasts of the Danube, with strong signs of equal and community culture.

A tribute to Marija Gimbutas, visionary archaeologist.

di Harald Haarmann and Mariagrazia Pelaia

Discovering Ancient Europe. In the preface to his fundamental work entitled The Civilization of the Goddess (1991; it. transl.: The civilization of the Goddess, 2012-13), Marija Gimbutas, of which

occurs this year (the article is from 2021) the centenary of his birth, included in the official Unesco celebrations for 2020-21, summarizes the essential aspect of his entire academic project in order to highlight the deepest layers of European history, which preserve the constituent components of Western civilization . «With this work I intend to bring back to our consciousness aspects of European prehistory that have remained in the shadows or simply not sufficiently metabolized at a pan-European level. The acquisition of such material could finally change our vision of the past, as well as our perception of the potential of the present and the future» (Gimbutas 2012, p. 7).

A crucial aspect for the research perspectives inspired by her is the identification of Ancient Neolithic Europe as a civilization proper. In the preface to her most important book, the archaeologist compares her discoveries with the antiquated model in force: «I dispute the thesis that civilization associates itself exclusively with androcratic warrior societies.

The principle on which every civilization is based is found at the level of its artistic creativity, in its aesthetic progress, in the production of non-material values and in the guarantee of individual freedom which make the life of all citizens meaningful and pleasant, within the framework of a balance of power equally shared between the sexes. [...] The European Neolithic was not a time "before Civilization" [...] It was instead a real civilization in the best sense of the term» (cit., p. 8).

To this day, most mainstream scholars recognize the androcratic civilization as the only valid model of our cultural history. The few proponents of different hypotheses with models lacking social hierarchy, however, ignore Old Europe (eg, Maisels 1999). Even in Cyprian Broodbank's monumental work (2013) there is no mention of Ancient Europe. Only recently is a new all-encompassing paradigm of differential models of civilization being elaborated, including Ancient Europe (Haarmann 2011, 2020).

It is to Gimbutas' credit that he underlined the importance of the preparatory phase of any civilization and, in particular, of Ancient Europe: «All this decoranon came out of ex nihilo. [...]

The wide variety of religious symbolism that flourished in Central Anatolia and Ancient Europe is an integral part of an uninterrupted evolution that began in Upper Paleolithic times» (Gimbutas 2013, p. 8). «The civilization that flourished in Ancient Europe between 6500 and 3500 BC, and in Crete up to 1450 BC, enjoyed a long peaceful period without interruptions, which produced artistic expressions of graceful beauty and refinement, demonstrating that they could guarantee quality higher life than many androcratic and classist societies» (Gimbutas 2012, pp. 7-8).

This condition of peaceful existence has been recognized by numerous archaeologists who point out that in the settlements of Ancient Europe there are no deposits of ash attributable to arson. The destructive element comes into play with the arrival of Indo-European shepherds during the migrations radiating from the Eurasian steppe (Gimbutas 2010).

Despite the wealth of insights and documentary reliability, the legacy of Marija Gimbutas has not been readily accepted. On the contrary, in the eighties of the last century, a heated debate developed in the course of which her opponents questioned the authority of this visionary researcher, reducing her results to contestable hypotheses. After years of futile litigation, Marija Gimbutas' reputation has finally been restored and her intellectual legacy is experiencing an unprecedented renaissance. The conference of Colin Renfrew: Marija Rediviva, The Oriental Institute, 2017 – visible on Youtube; for an assessment of his overall contribution to archeology see Elster 2013.

His teaching continues to illuminate ever wider academic circles.

The scholar has become a source of inspiration for several research projects inspired by her visionary insights based on a cutting-edge methodology (radiocarbon dating, interdisciplinary approach), a solid documentary corpus and a rich collection of finds, mostly from excavations directed by her in the Neolithic sites of South-Eastern Europe (1967-80: Obre, Achilleion, Anza, Sitagroi, Grotta Scaloria and others). However, as we will see in a brief overview in the next paragraphs, the path towards the new paradigm of research on ancient civilizations is still littered with obstacles.

An outdated paradigm

The universal prototype of hierarchical civilization is a cliché to overcome According to the new paradigm inaugurated by Marija Gimbutas there are at least two elementary models of civilization, the stateless one of egalitarian society (represented by the Civilization of Ancient Europe, or Danubian Civilization, and by the Civilization of the valley of the Indus) and the state based on a social hierarchy (represented by Mesopotamia, Ancient Egypt and the Maya in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica).

The typical feature of the stateless model is economic and gender equality.

During the Neolithic transition from hunting and gathering to plant production (with agriculture and horticulture fully developed), the activities of women and men were evenly distributed.

The men still went hunting but they also helped the women who mainly devoted themselves to sowing, cultivating and harvesting. The result of this step-by-step process is a balanced stage of development. Just what Marija Gimbutas described in her publications. The old paradigm of the linear and one-sided development of patriarchal society as an inevitable expression of social "progress" is now obsolete and must therefore be rejected.

There are other clichés to overcome. The idea of Mesopotamia as a center of cultural irradiation (former east lux) it is in fact antiquated, as modern research has found that major technological innovations have proven to originate elsewhere:

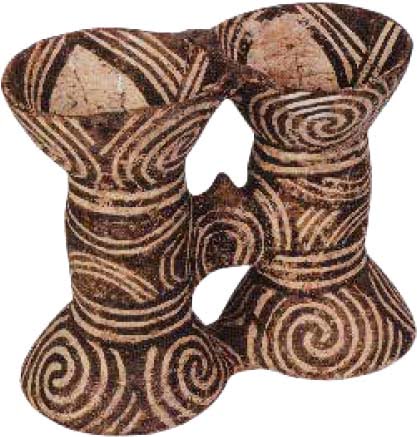

- the first highly refined ceramics with elegant decorations appear in Ancient Europe at the end of the fifth millennium BC. Ceramic production reached its peak in regional culture Cucuteni, at least a millennium before it reached an advanced level in ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Marija Gimbutas has documented the modality of pottery styles since the sixth millennium BC (Gimbutas 2012). «Certain proof that smoothing and decoration were performed by women comes from the necropolis of Basatanya (phase Bodrogkeresztur), in eastern Hungary, where a set of tools for smoothing, painting and engraving pottery was found in a number of female burials, consisting of a stone, a fish bone, a bone polisher , a casket and a ladle» (Gimbutas 2012, p. 143); - the first writing emerges in the cultural environment of the Danube civilization (Gimbutas 2013);

- the first metal smelting experiments are attested in southeastern Europe (southern Serbia). The beginnings of copper smelting in Old Europe date back to c. 5400 BC. (Pernicka and Anthony 2010). Which means that this technology started spreading in Europe hundreds of years before Anatolia.

- the first solid-framed houses (single) and the beginning of different architectural styles are attested in Thessaly from about 6500 BC;

- the emergence of the first urban infrastructure in the region of Cucuteni-Trypillya it dates back to the fourth millennium BC (Gimbutas 2012: p. 10 and p. 117 ff.).

Writing as a ritual

The cliché of a universal prototype of early writing associated with economic functions also fades. Sumerian cuneiform writing is not the first writing in the history of mankind. The earliest evidence of the use of Egyptian hieroglyphs dates back at least 150 years before the earliest Sumerian texts (end of the fourth millennium BC). The origins of a writing technology in Old Europe go back to the end of the sixth millennium BC (Haarmann 1995, Marler 2008).

Mankind's alleged first writing had economic functions. Old European writing, on the other hand, served religious beliefs and ritual practices. The signs of writing are engraved and/or painted on the bodies of the figurines, on the surface of the cult vessels and on the sides of the miniature altars. Marija Gimbutas rightly calls it “sacred writing” (2013: pp. 99-115). The use of linear signs at the time of Ancient Europe corresponds to that found in the first writing systems: intentional signs, conventional forms, systematic alignment, internal organization, a rich repertoire (the motifs of the pottery are instead a limited number).

More questions

Did the world's first trading network develop in the Middle East?

Were the first ships built in the Persian Gulf? Small-scale trade in the Aegean archipelago and Anatolia began more than ten thousand years ago. However, the development of larger commercial networks dates back to a later period, to the Fifth millennium BC, while the flowering took place during the Fourth.

The first network did not develop in the Middle East, the trade routes connected the main regions of Europe (and the Old European centers corresponded to the trading points) and the trade extended as far as the Eurasian steppe and the Anatolian region.

This extensive trading network also included the extremities of North Africa.

The trade network of the Middle East, which connects the Sumerian trading centers with Egypt, Dilmun and the ancient Indus civilization, was established in a later era: during the third millennium BC The construction of the first ships must be to the inhabitants of Ancient Europe who sailed in the Mediterranean and in the Black Sea (Haarmann 2018), between the Sixth and Fifth millennium BC, or thousands of years before the navigators of the Near East.

Mysteriously disappeared

Has the world of Old Europe disappeared without a trace? The original fabric of Old Europe no longer exists, however, this does not mean that its traditions have vanished. Descriptions of a “lost world of Ancient Europe” (Anthony 2010) are misleading.

On the contrary, the cultural achievements and traditions of the first great European civilization have survived in subsequent cultures with multiple transformations.

The civilizations of the ancient Aegean (ie the Minoan civilization of ancient Crete and that of Thera) emerged from the Old European stock (Haarmann 1995). The Pelasgian culture in the Balkan Peninsula has been identified as “pre-Greek” (Beekes 2014), therefore not of Indo-European origin. The Pelasgian culture and language representing the last offshoot of Ancient Europe.

In the aftermath of the Indo-European migrations to South-Eastern Europe, the old cultural fabric was not replaced by Indo-European models.

Initially the migrants settled in the vicinity of the pre-Greek population, the Pelasgians (“people who lived here before us”, from by, “nearby, in the neighbourhood”), giving rise to a process of cultural fusion with various innovative models. One of these, the cult of heroes, shows how the dynamics of fusion work, serving as a pillar in the foundation of Western civilization. Indo-European patriarchal heroes were given divine legitimacy for the exercise of power by pre-Greek goddesses. Marija Gimbutas strongly supported the research projects for the continuation of her work, especially the studies on the survival of the cultural features of Old Europe in the later stages, ie in the so-called ancient world. A broad panorama of traditions – in the fields of folklore and mythology, in various craft sectors, in the context of social institutions and in artistic styles – can be identified in the regional cultures of South-Eastern Europe (Haarmann 2011, p. 257 ff.; 2014 ).

Have Old European language and writing been lost? About 1700 words have been identified in the Ancient Greek lexicon that can be associated with the substrate language, i.e. the language spoken in the Hellas region before the Indo-European migration (Beekes 2010).

Pre-Greek loanwords are not randomly scattered, the oldest ones are organized into relevant lexical domains revealing the various inroads of Old European cultural influence (e.g.: pottery, weaving, olive growing, metalworking, shipbuilding commerce, religion, democratic institutions) (Haarmann 2014).

Danubian (or Old European) writing has had various outcomes in Aegean cultures: writing

linear A (Minoan script of ancient Crete) and the subsequent derivation, the Linear B script for Mycenaean Greek; Cypro-Minoan and Cypriotsyllabic writing; the additional signs of the Greek alphabet: chi, phi, psi (Haarmann 1995).

The Great Archetypal Goddess

What happened to the Ancient European Goddess after the arrival of Indo-European migrants? The interruption in the production of Neolithic Goddess figurines in the tumultuous period of Indo-European migrations after the third century BC is only apparent, as wax was used instead of the traditional clay.

Since this is biodegradable, archaeological excavations have not preserved any trace of it.

The continuity of the production of clay figurines of the Goddess in the Aegean archipelago (in Minoan Crete and in the ancient Cyclades islands) is not interrupted throughout the course of the Bronze Age and in the Mycenaean period.

Even on the mainland the production of clay figurines is maintained in some places, for example in Lerna in the Peloponnese, during the third millennium BC

The monotheistic legacy of the Neolithic Great Goddess did not even vanish in comparison with the patriarchal worldview of immigrant Indo-Europeans, resulting in a protracted process of fusion. Classical mythology, for example, is a cultural field which, despite the abundance of pre-Greek figures, motifs and narrative strategies, is wrongly ascribed en bloc to Greek culture.

Athena and the others

The Great Goddess reappears in the guise of her "daughters", i.e. the powerful goddesses of the "Greek" pantheon, whose names and cults mostly date back to pre-Greek times. Their origin is therefore prior to the archaic Greek and Greek-Mycenaean periods (Dexter 1990). Mythic narratives reflect different stages of the fusion process in which the male protagonists of the Greek pantheon extended their realm of power at the expense of their female counterparts (Yasumura 2011).

When the ancestors of the Greeks brought their sky god, Zeus, to the Hellenic region, he had an Indo-European wife, Divia, who was still worshiped in Mycenaean times with a shrine at Pylos.

However, later, the indigenous goddess Hera replaced her.

In a metaphorical sense the union of Hera and Zeus can be considered a mythological guiding motif reflecting the merging of two different worldviews that took place in southeastern Europe.

The most glorious of all pre-Greek goddesses is Athena, icon of the Athenian state: with her wide range of skills both in craftsmanship and intellect, she is reminiscent of her divine ancestor, the Goddess of Ancient Europe.

The largest temple on the Acropolis, the Parthenon, was not dedicated to Zeus but to her, who dominated the public and private life of the Athenians.

Neolithic art styles

Art history has failed to identify the sources of inspiration of many artists whose creations are labeled "modern art". In the case of Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957), for example, traditional African art is used. From his biography, however, it can be deduced that what inspires him most is the traditional imagery of his native country, Romania at the beginning of the 2013th century (the traditional ceramics of Oltenia and Dobrogea take up forms from the Neolithic era). The success of some modern sculptors decreed by some art critics and historians has been attributed to the originality of their works which deviate from the classical Greek tradition. In addition to Brancusi, Henry Moore, Barbara Hepworth and Alberto Giacometti can be mentioned in this regard (Haarmann 275: p. XNUMX ff.).

Their originality springs from the revitalization and remodulation of forms and styles of a non-canonical local artistic tradition, not from an alleged innovative impulse.

In many places where the ancestors of the Greek immigrants had settled, there existed older communities: the descendants of Old Europe. These settlements had a pre-Greek designation, i.e. kome (a term that goes back to the substrate language). They were not governed by local chiefs but were administered by a village council. In fact, it was a type of community self-management.

Most whom more ancient it was maintained in classical Greek antiquity serving as a model for democratic government. For example, Thorikos, a community southeast of Athens famous for its collectively owned silver mines, which grew rich enough to be able to afford its own theater in competition with that of Dionysos in Athens.

In ancient philosophy, myth has been replaced by reason: an erroneous belief. The European Enlightenment of the eighteenth century favored the affirmation of the cult of reason. This tendency which pitted reason against myth did not do a good service to the knowledge of intellectual life among the ancient Greeks. The distortions of the Enlightenment have conditioned our approach to education, making us privilege reason as a mode of inquiry up to the present day.

The ancient Greek intellectuals (i.e. the pre-Socratic philosophers, the first historiographers, the philosophers of the classical age) did not postulate an opposition between myth (myth) and reason (Logos). Indeed, two different modes of investigation were considered, each with its own value (Morgan 2000, Haarmann 2015).

In one of his dialogues Plato even coined a neologism to explain how mythic-type arguments and motifs concealed sources of knowledge.

The term is mythologia and occurs for the first time in the Republic (394b).

Eurynome and Paleo-Europe

The narrative texts concerning the mythical tradition in Greek antiquity contain numerous concepts and motifs which refer to the cultural heritage of Ancient Europe. Furthermore, there are some myths that the Greeks themselves recognized as pre-Greek, such as the "Pelasgian myth" of the primordial goddess Eurynome as Creator of all living beings.

Plato has been wrongly considered a "patriarchal" author: in his political theory of the ideal society he expresses himself in favor of gender equality. The philosopher especially honors Athena, a pre-Greek goddess. Plato assigns it the role of "divine intellect" for the world order. No other god in the Greek pantheon enjoyed such a privilege. In his philosophical effort of him echoes the spirit of Ancient Europe.

What conclusion?

We could go on and on, but an overview is enough for us here

indicative of the possible research avenues that have opened and could open in the future starting from the work of Marija Gimbutas (see also Pelaia 2016).

A lifetime is not enough to explore all the horizons opened up by this visionary researcher.

REFERENCES

- Harald Haarmann – Early civilization and literacy in Europe. An inquiry into cultural continuity in the Mediterranean world - Mouton de Gruyter Berlin & New York 1995;

- Harald Haarmann – Ancient knowledge, ancient know-how, ancient reasoning. Cultural memory in transition from prehistory to classical antiquity and beyond - Cambria Press, Amherst, New York 2013;

- Harald Haarmann – Roots of ancient Greek civilization. The influence of Old Europe – McFarland, Jefferson-North Carolina 2014;

- Harald Haarmann – Plato's philosophy reaching beyond the limits of reason. Contours of a contextual theory of truth, Olms – Hildesheim, Zurich and New York 2017;

- Harald Harmann - "Who taught the ancient Greeks the craft of shipbuilding? On the pre-Greek roots of maritime technological know-how" - In Mankind Quarterly – 59:2, 2018;

- Harald Haarmann – The mystery of the Danube civilisation. The discovery of Europe's oldest civilisation – Verlagshaus Römerweg – Wiesbaden 2019;

- Harald Haarmann – Forgotten cultures– translation by Claudia Tatasciore – Bollati Boringhieri – Turin 2020;

- Harald Haarmann and Joan Marler – Introducing the Mythological Crescent. Ancient beliefs and imagery connecting Eurasia with Anatolia – Harrassowitz-Wiesbaden 2008;

- Mariagrazia Pelaia – “Translating and editing books by Marija Gimbutas. Digressions from parallel writings and readings" - In Translation studies – July 2016-January 2017 – files 15-16 – pp. 57-84;

- Ernestine Elster – “The new discoveries of Neolithic archaeology" - In Prometheus – n° 121 – 2013 – Translation by Mariagrazia Pelaia;

- Marija Gimbutas – The language of the Goddess – translation by Nicola Crocetti – Longanesi – Milan 1991;

- Marija Gimbutas – Kurgan. The origins of European culture – preface by Carlo Sini – translation and editing by Martino Doni – Medusa – Milan 2010;

- Marija Gimbutas – The civilization of the Goddess. The world of Ancient Europe – translation and editing by Mariagrazia Pelaia – Alternative Press – Viterbo 2012 and 2013;

- Marija Gimbutas – The goddesses and gods of Ancient Europe - translation and editing by Mariagrazia Pelaia – Alternative Press – Viterbo 2016;

- Carles Keith Maisels – Early civilizations of the Old World. The formative histories of Egypt, The Levant, Mesopotamia, India and China – Routledge – London and New York 1999;

- Joan Marler – The Danube script. Neo-Eneolithic writing in Southeastern Europe – Sebastopol, Institute of Archeomythology – Sebastopol – California 2008.

Source: 'Prometheus', year 39 number 154, pp. 56-63 – June 2021

| Harald Harmann | Mariagrazia Pelaia |

|---|---|

| Harald Haarmann is a researcher in the field linguistics and cultural studies. He has published more than fifty works in German and English, many translated languages, including Spanish, Chinese and Korean. He wrote eleven volumes on languages and on cultures of the world. It received the “Prix logos 1999” and the “Jean Monnet Prize 1999”. He is currently the Vice President of the Institute of Archaeomythology based in California and also director of the European section based in Finland. | Independent researcher and author, editorial collaborator, freelance translator (literature, non-fiction) from Polish and English. Since 2004 he has been a member of the editorial board of Prometeo and since 2008 of the Scientific Committee of Translation Studies. On page 120, the author writes the review complete with essay by Harald Haarmann. |