di Arianna Carta

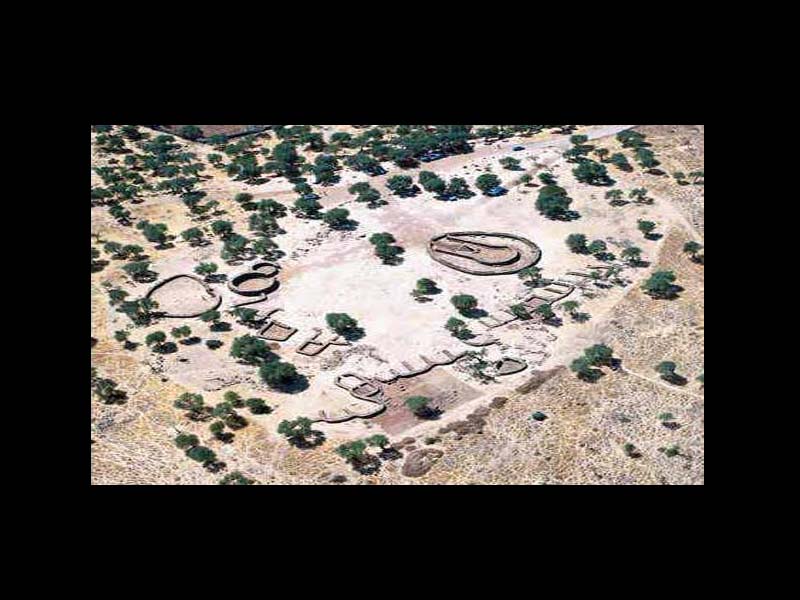

Sardinia is an open-air temple dotted with sacred events or, to quote Eliade, hierophanies: nuraghes, domus de janas, giants' tombs, menhirs and sacred wells that blend with zoo and anthropomorphic rocks (moon valley, elephant, bear rock etc.) caves, earth, sky, water, fire and the stars. Ancient land and landscape of the soul dotted with symbols, archetypes, constructions and artefacts on which scholars still rack their brains.

Much has been written about the well of Santa Cristina, both at an archaeological, architectural and even astronomical level, but few scholars have tried to tackle the terrain of the sacred, by its nature elusive and full of pitfalls.

In this brief research I will try to bring to light some aspects concerning the sacred feminine, focusing on the symbolic elements (for the basic characteristics of the structure, please refer to the relevant file).

Obviously the possible reconstruction of cults and rites of prehistoric times, while making use of the findings and precise stratigraphic excavations, can only remain within the ambit of hypotheses. But if, as Marija Gimbutas wrote, the stones speak, let's see what those of Santa Cristina have to say.

The "father" of Sardinian archeology and the well of Santa Cristina

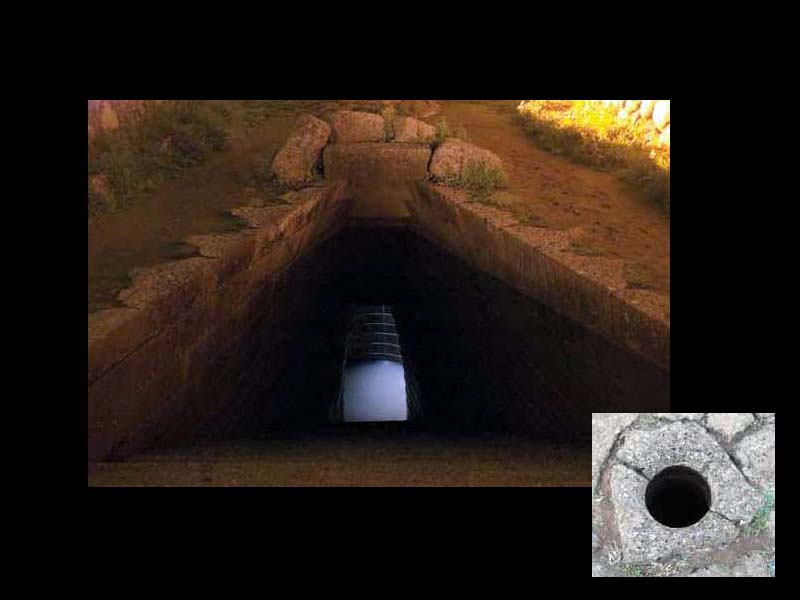

One of the archaeologists who has contributed most to Sardinian archeology is certainly Giovanni Lilliu, a prolific archaeologist awarded the honor of "Sardus Pater". In his monumental text entitled "The civilization of the Sardinians from the Paleolithic to the age of the nuraghi" the scholar also deals with the sacred wells, stating that "the most important monuments of sacred architecture of the Nuragic age are the well temples or sacred wells.” According to the archaeologist, the sacred ceremony officiated by a priest or priestess took place in the vestibule and the staircase had the sacred value of connection with the underground kingdom. In his essay Lilliu analyzes several wells on the island and when he describes the well of Santa Cristina he asserts that this temple "represents the pinnacle of water temple architecture."

The main elements

To begin to understand how much this well is linked both to the (symbolic) sphere of the sacred and to that of the feminine, we can start from the name: Well of Santa Cristina. What a structure of the eleventh century. BC is officially associated with a saint (where officially means both the sphere of the Christian religion and the archaeological academic one), it is not an element to be underestimated.[1] And if the superficial explanation is the presence of a small country church located in the vicinity of the structure, whoever studies the traces of the past knows how to recognize a clear indication of appropriation typical of the dominant (or rather, incoming) religions, i.e. the practice of incorporating elements of the previous cult (in this case "pagan" or pre-Christian) which on the one hand guarantee continuity and on the other avoid dangerous tears in the socio-cultural fabric.

The other important elements are: the vulvar representation, the theme of the descent into the afterlife, the purifying element of water, the theme of the double and that of the ladder (which lead to the double ladder), that of the upside down (the world above like the one below), the chthonic symbology linked to the cave, the sun, often identified with the masculine principle, and the moon, considered by most of the sources more as a feminine principle.[2]

The vulva

The perimeter of the sacred well, which using an unfortunate archaeological terminology is defined as "key lock", represents a gigantic and I would say rather detailed reproduction of the vulva which, like the hundreds of Neolithic finds, statuettes in primis, signals possible cults linked to female divinities or at least a sacralization of the female body.

The associations with the female genital organ do not end here: the staircase enters the ground and reaches the circular body of water, surmounted by a tholos which the architect Larner defines as having a peculiar "uterine neck" shape. The hypothesis of the connection with the female deity Tanit comes from the same scholar[3], also considered the discovery of the statuettes of the Phoenician era.

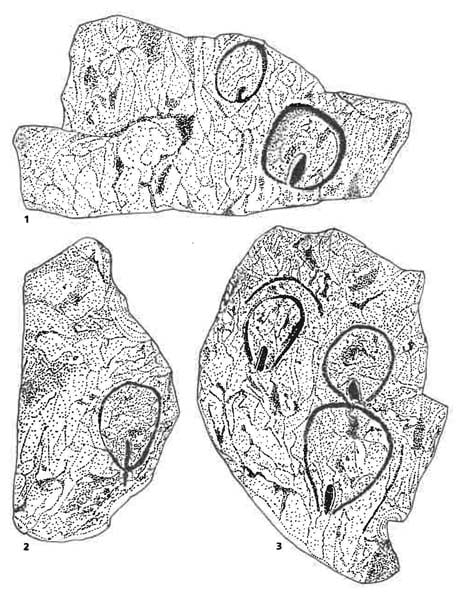

The archaeologist Marija Gimbutas investigated the theme of the vulva linked to birth and rebirth and, in one of her best-known essays, talks about vulvar representations that span most of prehistory, and begin well before the birth of agriculture. According to the scholar, the first petroglyphs begin to be found in the Aurignacian period or about 32.0000 years ago. These are rather schematic but clear images which, through the metonymic figure of the “part for the whole”, would represent the Great Goddess, often connected, in later times, with the aquatic element.

The representations of the vulva and female belly therefore characterize a large part of the prehistoric era, both alone and associated with aquatic elements, shells, seeds and buds, fruits, symbols of fertility and the creation of life.[4]

The cult of the waters

There are many symbols linked to water, and widely discussed by scholars such as Gimbutas, Eliade, who speak of (re)generation, birth and rebirth. In his dictionary of symbols, Chevalier devotes several pages to the complex symbolism of water in various cultures and codifies water on the basis of three fundamental themes, such as "source of life, means of purification and center of regeneration”. According to scholars this element is also linked to initiatory themes pertaining to the feminine sphere and is associated with the moon.

Neumann, bringing the woman back to the archetype of the container/vase, considers water symbolically linked to the feminine "understood as the primordial womb of life”. In this scholar's vision, the well becomes the means that allows access to the underworld, the realm of mother earth.

Gimbutas shows how the sacredness of water, as a life-giving element, dates back to prehistoric times and reaches the present day, manifesting itself and materializing in the cults linked to springs, water sources and sacred wells. The association of female divinities and nymphs is demonstrated by innumerable historical and folkloric sources supported by archaeological data, for example the discovery of female statuettes, vases with aquatic motifs, etc.[5]

According to Eliade the waters symbolize death and rebirth being "fons and origo". "contact with water always involves regeneration because on the one hand dissolution is followed by a 'new birth', on the other hand immersion makes life fertile and multiplies the potential.” Immersion in the waters therefore means new life because the waters are “purifiers and regenerators”. Furthermore, according to the scholar, the church has appropriated the soteriological values of the waters and the death-rebirth symbolism connected to baptism.

Even the archaeologist Maria Grazia Melis agrees that the cult of water in Sardinia is closely linked to the female sphere, indicating "the feminine character of the cult” while emphasizing a male co-presence represented by the bull. The scholar confirms the preponderance of this cult in the Neolithic period and its attestations which also persist during the Bronze and Iron Ages.

The association of the bull with the male element, taken for granted in the archaeological field and beyond, seems to be a patriarchal cultural legacy, also refuted by the association between the animal's horns and the lunar quarter which, according to Eliade, is a symbolism of very ancient origins[6]. The connection between the horns of the bull/cow (in the Egyptian context[7]) and the crescent moon after all, is much more relevant to monuments such as the Well of Santa Cristina, in which a clear link can be found between feminine symbology, the moon and the aquatic element.[8]

The historian of religions Vittorio Lanternari wrote about the cult of water in Sardinia, who in his essay combines archaeological data with ethnographic research, historical sources, iconography and popular traditions. The scholar, while linking the cult to the male divinity of the Sardus Pater, defines the paleo-Sardinian cult of the waters as "indigenous and universal” as justified by the enormous diffusion of sacred wells on the island. The scholar also confirms the sacred function of the wells, whose structure is too complex and elaborate to have a practical function. Lanternari, following Pettazzoni's footsteps, compares the water cult of the indigenous Australian and Sardinian populations, however, highlighting a major difference: while the Australian hunter-gatherers celebrated rainwater (giving rise to uranic myths), for the proto-Sardinians the cult turns to spring waters. Lanternari disconnects the wells from the cult of the ancestors to connect it, on the basis of archaeological finds such as breast stones, doves, the bronze statuette of a mother with ithyphallic son and numerous statuettes of animals (rams, deer, oxen)[9], to fertility/fecundity. Lanternari also points out the “pagan-Catholic syncretism”, referring to the appropriation of the holy wells by the Church which “he skilfully incorporated an archaic pagan element into Christian sacred mythology."[10] The interesting element is that the people, together with the priests who blessed the water, celebrated the cult on the day of March 1771, coinciding with the opening of the agricultural season, a discrepancy too evident for it not to be noticed by the Church which in fact he abolished the cult of the well in XNUMX. As regards the symbolic link between water and women in Sardinia, Lanternari mentions the tradition of Ghilarza, clearly of agricultural origin, in which a litter is built with ferula branches and grass which is carried procession through the town, while the women from the windows spray jets of water on it. The symbolic value of this rite is clearly linked to fecundity/fertility where it is precisely the female element that favors (pro)creation. In another place dedicated to Saint Lucia, in Bonorva, the archaeologist Taramelli has found a sort of amphitheater that surrounds the pools of medicinal water. This was the space where the community gathered to witness the ordeal according to Taramelli and Lanternari. Since the reference to this practice is not supported by any archaeological or other evidence, I find it more pertinent to hypothesize healing ceremonies. It should be noted that, due to the same syncretic process, the structure in the Christian era took on the name of a saint who, precisely, cures ophthalmic diseases.

The Moon as a "star" of the rhythms of life

There are several scholars who connect the moon to the cycles of life and to the feminine sphere. According to Chevalier and Gheerbrant, the moon represents the feminine principle and is a symbol of transformation and growth, while according to Eliade the moon is par excellence the star that symbolizes the cycle of life. According to Neumann "the privileged spiritual symbol in the matriarchal sphere is the moon, which is related to the night and to the Great Mother of the nocturnal sky", while in general the scholar observes how "from an archetypal point of view luminous bodies always constitute symbols of the conscious and spiritual aspect of human life”. According to the scholar, the moon is connected to the theme of rebirth.

According to Durand, water is an element with a feminine value, also for the liquid element of menstruation, and he adds that "on the one hand the waters are subjected to the lunar flow and on the other, having a germinative character, they join the great agricultural symbol that is the moon.”[11] After all, most of the myths associate the moon and water with the same divinity (for example the Iroquois, the Babylonians, the Persians – with the Persian goddess Anahita Ardvisura -, for the Mexicans the moon is the daughter of Tlaloc, the divinity of the waters).[12] The moon is inextricably linked with death and femininity, and it is through femininity that it unites with aquatic symbolism.

According to Eliade: “the moon is the universal measuring instrument…the same symbolism connects the Moon, the Waters, the Rain, the Fertility of women, that of animals, vegetation, the destiny of man after death and the initiation ceremonies."

Moon and waters: the moon by its very nature is closely linked to the cycle of life: it is born, grows andmuore” to then be reborn and this makes it the star that par excellence symbolizes cyclicality, becoming, fertility. For Eliade, the moon, biologically linked to the menstrual cycle and therefore to fertility, was also used in all ancient populations as a means of measurement. The connection between water and the moon, expressed by the tides, has been noted since the most remote times by many populations, from the Greeks to the Celts, the Maoris and up to the Eskimos.

The moon is a symbol of the transition from life to death, which is why many lunar deities, such as Persephone, are also chthonic and funerary. According to Chevalier in fact, “the moon is both the door of heaven and the door of hell, Diana and Hecate, the sky in question is the culmination of the cosmic edifice. The exit from the cosmos will be effected only through the solar door. Diana will be the favorable aspect, Hecate the fearful aspect of the moon”. Isis, Istar, Artemis or Diana, Hecate, are all female divinities linked to the moon: the connection with the Neolithic Great Goddess is inevitable.[13]

Even if we didn't want to consider all the symbolic aspects, according to the archaeologist Lebeuf, the well represents one of the best examples of an astronomical observatory in the Mediterranean area. The tholos of the well, thanks to the particular arrangement of the set back ashlars, in fact makes it possible to measure the lunar movements and predict their eclipses. It should be noted that every 18,61 years the moon is reflected on the surface of the water at the bottom of the well, reaching its maximum height on the occasion of the lunistice. Furthermore, from a scenographic (and symbolic) point of view, the scale of light that is created during the full moon is particularly relevant.

The upside-down double ladder

The symbology of the staircase as an element of relationship and connection between heaven and earth "almost universal”, concerns the spiritual (gradual) ascension, and in its verticality indicates the ascent. The world tree can be connected to it and in the Bible it is represented by Jacob's ladder, on which the angels went up and down. The ladder is present in many cultures and philosophies such as Buddhism, and it is an element that we also find in Siberian shamanic rites with the 7 rung birch ladder, in the mysteries of Mithras it becomes a symbol of the degrees of mystical ascension, etc. In Egypt, various ladder-shaped amulets have been found in archaic or medieval dynasties. Durand also describes the ladder as a symbol of ascension (of immortality), linking it both to the cult of Mithras and to shamanism and Jacob's ladder.

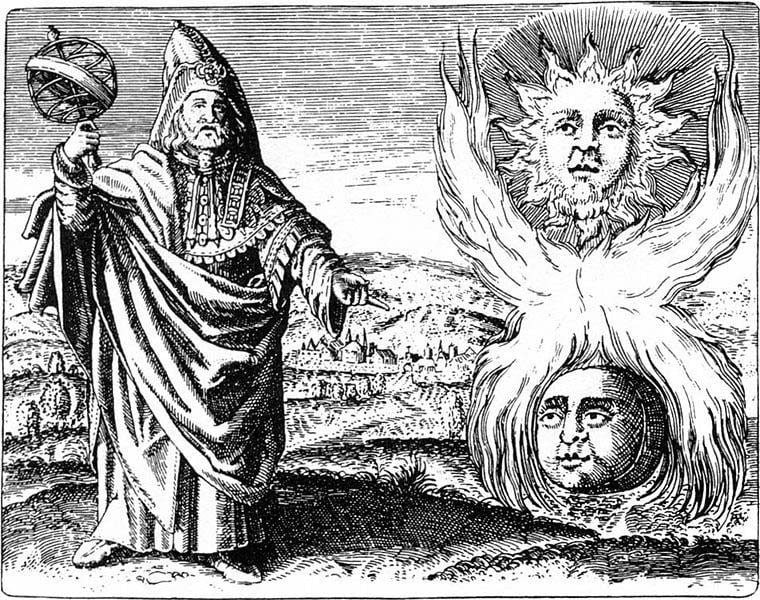

René Guénon, an expert in sacred symbolism, has written a lot about axial and passage symbology. The inverted double staircase of the well of Santa Cristina, in its descent towards the lustral source, is certainly a splendid material realization of this concept. The axial symbols par excellence, which represent the passage between the worlds (earthly and afterlife), are: the world tree on which one can climb, the bridge, the connecting element par excellence and the double staircase, whose symbolic is particularly strong, allowing both the movement of descent and ascent through the steps, material and concrete expression of the "levels or degrees of universal existence” and as such linked to initiatory rites. Also Coomaraswamy in his investigation of the symbolism of the inverted tree, reflects that “the Axis of the Universe is like a ladder on which a perpetual ascending and descending movement takes place.” Metaphor and analogy taken from hermetic philosophy and the alchemists who decreed the association between above and below, what is above is like below.

The discourse of the upside down is equally rich in symbolic elements and has to do with the passage towards death, just think of the representation of Dante's hell (in which we also find the element of water when crossing the river). The surface of the water, which in the well of Santa Cristina allows the vision of the upside-down shadow, according to Guénon, should be considered as an analogical plane of reflection in which what is above is mirrored, i.e. the "supra-cosmic sphere" , with what is below, or the "cosmic sphere."

From a purely archaeological point of view, although the sacred well is not a structure for funerary use, we can suggest a connection with the upside-down anthropomorphic petroglyphs of the tomb of Sa concas (Oniferi) or of the Branca-Cheremule tomb of which write Lilliu and P. Melis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the symbology of lustral water in direct association with the two "stars” par excellence, sun and moon, the theme of the upside down/world above-world below, the staircase as axis mundi, the steps as degrees of existence, the representation “cyclopean” of a vulva whose entrance allows you to immerse yourself in the earth to touch the water, allows us to hypothesize the practice of cults linked to the sacred feminine. Although not certain about it, it is very probable that priestesses officiated the rites linked to the cycle of life, death and rebirth. Since there are no direct written sources in this regard, clearly we must remain within the ambit of hypotheses but, in the case of the well of Santa Cristina, the clues are such and many as to lead in the direction of a cult of the Great Goddess on which Marija Gimbutas has written so much .

Footnotes

[1] Regarding the association between female saints and holy wells, see also the sanctuaries of Santa Vittoria of Serri e Saint Anastasia of Sardara

[2] According to Chevalier and Gheerbrant, in all ancient Indo-European languages the sun was feminine. Scholars also cite the Dogon of Mali whose cosmogony is lunar and the sun represents the female element; see Luciana Percovich (2007) for an interesting analysis on the feminine roots of the sacred and a critique of the dualistic polarization of knowledge

[3] Female divinity of Phoenician origin, connected to the goddess Astarte; her symbolic elements are the dove, the palm and the pomegranate

[4] Please also refer to the fact sheet female figurine (Venus-vulva) of the shelter Gaban

[5] In this regard, please refer to the article by Barbara Crescimanno Nymphs and waters in Sicily. A sacred relationship

[6] Eliade (2008) associates the symbolism of the horns as a double representation of the new moon

[7] On the Vedic cow goddess, see Eliade (2008)

[8] In the Egyptian context, moreover, the cow/bull was the animal consecrated to Isis and Hathor, female divinities who embody the Universal Mother and nature. The even more significant element is that it is the sun and the moon that represent the goddesses, as demonstrated by the iconography of the cow's growing horns and the solar disk. According to EO James, Anat "lady of the mountain" or "lady of the sky" is also associated with a wild cow, a symbol of the Great Mother in Western Asia and Egypt

[9] In the well temple of Santa Anastasia di Sardara there is a taurine protome

[10] Referring to the wells in general but to the one near Bosa called "De sos tre res, that is, of the three wise men.”

[11] In support of this thesis, the scholar cites various mythologies that unite the moon and water, (see also Eliade 2008)

[12] Eliade (2008)

[13] On the woman-moon association, or rather phases of the moon and menstruation, admirably clarified by the Lady of Laussel, see the contribution by Luciana Percovich on Sacred Feminine

Ariadne Carta – 2021

REFERENCES

- Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrant – Dictionary of symbols: myths, dreams, customs, gestures, shapes, figures, colors, numbers – Milan Rizzoli 1992;

- Ananda Kentish Coomaraswamy – “The Inverted Tree” – in Quarterly Journal of the Mythic Society of Bangalore – 29, p. 1–38–1938;

- Gilbert Durand – The anthropological structures of the imaginary. Introduction to general archetypology – Daedalus editions – Bari 2013;

- Mircea Eliade – Images and symbols – Jaca Book – Milan 2018;

- Mircea Eliade – Treatise on the history of religions – Bollati Boringhieri – Turin 2008;

- Marija Gimbutas – The language of the goddess – Rome 2008;

- René Guénon – Symbols of sacred science – Adelphi – Milan 2000;

- Oliver James Edwin – Ancient Mediterranean gods – The Assayer – Milan 1963;

- Vittorio Lanternari – Prehistory and folklore: ethnographic and religious traditions of Sardinia –The Asphodel – Sassari 1984;

- Frank Larner – History, technology, architecture and astronomy – Editions Flap – Mestre 2008;

- Arnold Lebeuf – The well of Santa Cristina is a lunar observatory – TlilanTlapalan – 2011;

- Arnold Lebeuf – “Nuraghic Well of Santa Cristina, Paulilatino, Oristano, Sardinia” – in Handbook of Archaeoastronomy and Ethnoastronomy – Springer Science+ Business Media – New York 2015 – pp. 1413-1420;

- Simona Ledda – “Demetra: reasons and places of worship in Sardinia” – in Insula: Notebook of Sardinian culture – no. 6 - 2009 - p. 5-24;

- Giovanni Lilliu – The civilization of the Sardinians from the Paleolithic to the age of the nuraghi – The Mistral – Nuoro 2017;

- Maria Grazia Melis – “Observations on the role of water in the rituals of prehistoric Sardinia” – in Journal of prehistoric science – LVIII – 2008 – pp. 111-124;

- Paul Melis – “Pre-nuragic religiosity” – in Prehistoric Sardinia, history, materials, monuments – Carlo Delfino Publisher – Sassari 2017;

- Alberto Moravetti – The Nuragic Sanctuary of Santa Cristina – Guides and Itineraries – Archaeological Sardinia – Carlo Delfino publisher – 2003;

- Erich Neumann – The great mother: phenomenology of female configurations of the unconscious – Astrolabe – Rome 1981;

- Luciana Percovich – Dark shining mothers: the roots of the sacred and of religions – Venexia Publishing – Rome 2007;

- Julien Ries – Man and the Sacred in the History of Humanity – Jaca Book – Milan 2007;

- Giuseppa Tanda – “Funerary Hypogeism in Sardinia” – in Prehistoric Sardinia, history, materials, monuments - Carlo Delfino Publisher - Sassari 2017 - pp. 111-135.