di Maria Laura Leone

During the works for the reopening to the public of the Pulo di Molfetta (Bari), in 2020, two engraved pebbles emerged whose interest falls within the sphere of prehistoric art (source). The meaning of art, as we understand it today, is far from what we attribute to the mass of painted, incised and sculpted signs, on stone, bone and rocky walls, indoors and outdoors, practiced before the use of writing alphabetic. This production, present all over the world except at the Poles, gives us back a part of the abstract thought of a distant past and the term "art" is applied to it for a reference synthesis.

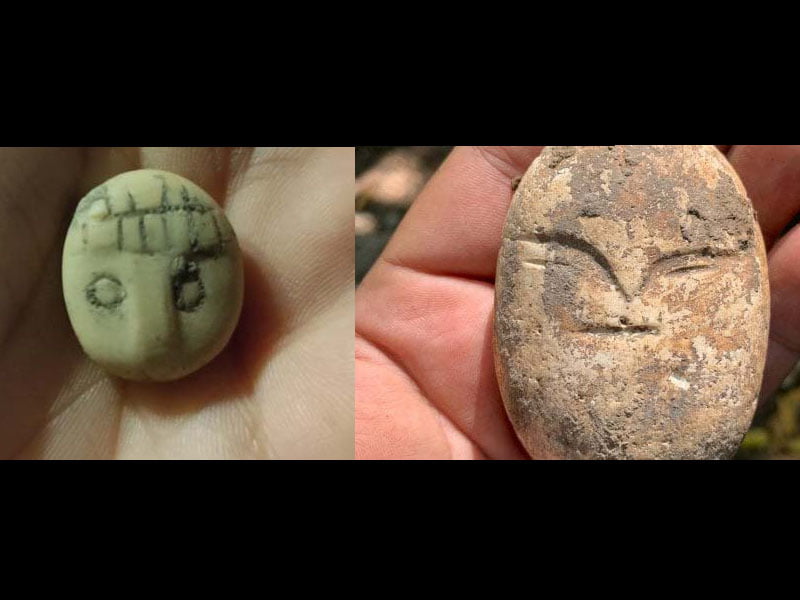

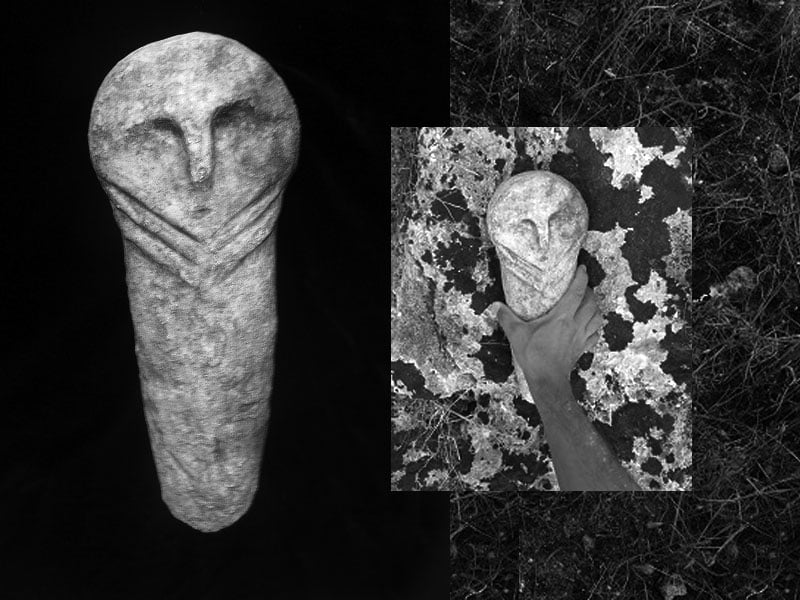

The first pebble recovered (A), larger than the second, is a whole head without the neck with the somatic features of a face engraved on the front, a zig-zag motif is engraved on the back; a symbolic factor whose value is often referred to water. The face is reduced to a continuous brow ridge, including the nose, while the eyes and mouth are rendered with a narrow slit. This pattern is called a T-face.

The second perfectly rounded pebble (B), found after a short time, is much smaller and represents only the eyes, the nose and a hairstyle on the head. The face is not complete, the mouth and chin are missing, the grid decoration on the head also continues on the back of the small stone.

The two smileys are very different in style and in the workmanship, they seem to belong to two different chronological horizons: the pebble A to the Neolithic, the smaller one (B) to the Paleolithic or its final phase.

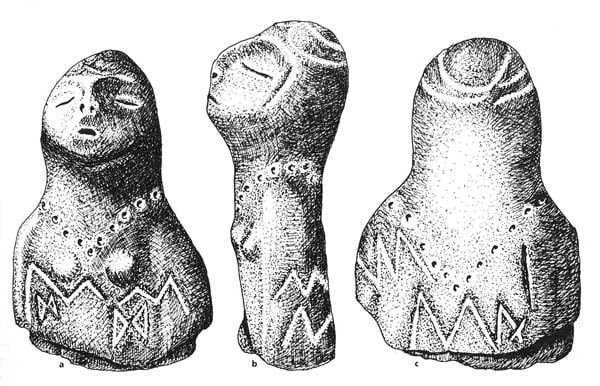

The representations with the facial T are placed between the Neolithic and Eneolithic and Puglia shows some examples with the small statuettes of Cala Scizzo (monopoly)[1] e Pacelli cave (Castellana Caves)[2] and the phallic-anthropomorphic Eneolithic idol[3] di Arnesano (Lecce)[4].

As far as the slit eyes are concerned, the comparisons are always in Puglia, with the female statuette of Canes of the Battle (Museum of Canne, Barletta), that of Raven Pass (Museum of Manfredonia)[5] and the female protome of Cave of the Deers in Porto Badisco (Museum of Taranto).

In each of these specimens the eyes are closed, as in subjects immersed in an ecstatic or meditative condition[6]. In the figurine of Passo di Corvo this immersion is even more effective because of the ajar mouth. A further comparison for the slit eyes can be made with the Neolithic figurines of the Yamurkian culture of Shaar Golan in Israel, where about a hundred engraved pebbles and clay statuettes have faces schematized with slit features. Some of these finds also reproduce sexual organs, male and female, and have been linked to some magical rite or fertility cult[7].

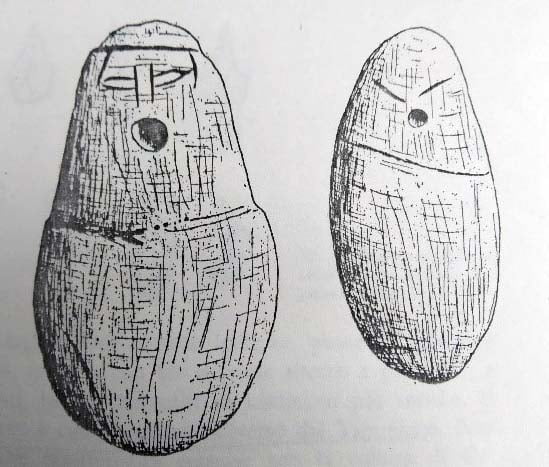

As far as the smaller pebble is concerned, the physiognomy with the pillar nose and circular eyes is quite singular, but not rare, instead we find the grid hairstyle in the Upper Paleolithic, especially in the Gravettian area (around 25.000 years ago). The most accurate comparison is with Brassempouy's head[8], known as the lady with the hood but also with a Venus found in 2019 in Renancourt (Amiens, France)[9].

On these figurines the head is decorated with a typical elaborate headdress, also identified on Paleolithic women buried in caves, such as the "mother of Ostuni"[10]. In these two cases it is a cap made with small sewn shells, covered with a thick blanket of red ocher; another analogy is with the famous Venus of Willendorf.

This hairstyle could be a properly female sign of distinction within a social structure or group, linked to the artistic-spiritual-sepulchral contingencies in the cave[11].

On both pebbles, the desire to represent a precise entity is very vague but both show a perhaps female or childish face, rather than a male one. In fact, we find the male face depicted in Paleolithic art and it always has a beard.

Molfetta's two facial expressions do not express a direct relationship with the sphere of fertility or fecundity, but could recall an anthropomorphic conceptuality, yet to be framed, which would not exclude that of apotropaic and/or votive gender. Dating is a crucial point on which to advance other deductions. The Pulo di Molfetta, or karst chasm not unlike those of Altamura and Gravina, was investigated at the beginning of the twentieth century by Maximilian Mayer, and more recently by Dr. Francesca Radina, from 1995 to 2003[12]. The testimonies collected during the excavations frame a frequentation that took place between the Mesolithic and the Middle and Lower Neolithic (VIII-IV millennium BC). It is hoped that the direct investigations on the objects will provide further elements to this stylistic analysis. They will be addressed to the origin of the materials, the details of the executive technique, the ergonomic parameters of the realization of the object and more. Therefore, we just have to wait for these results and insights into the recovery environment. The advanced preliminary dating falls within the archaeological context of Pulo.

Maria Laura Leone – 31 January 2021

Footnotes

[1]Geniola-Tunzi 1980.

[2]Striccoli 1988.

[3]Leo 2000, fig. 2; p. 139.

[4]Graziosi, Cocchi Genic 1996, vol. 2, p. 245.

[5]Gimbutas 2008, fig. 36.

[6]Leo 2009, p. 67, fig. 65.

[7]Anati 1963, vol. 2, pp. 307-9, figs. 8, 9, 10.

[10]Coppola 2013; Leo 2006.

[11]Leone 2015, de Nardis 2021.

[12]Mayer 1904; Radina 2007.

REFERENCES

- Emmanuel Anati – Palestine before the Jews – 2 volumes – Il Saggiatore (Milan) – 1963;

- Daniela Cocchi Genic– Prehistory Manual – 3 volumes – Ed. Octavo (Florence) – 1996;

- Donato Coppola – The shelter of Agnano in the Upper Paleolithic. The Ostuni burial and its symbols - Ed. Earth - 2013;

- Alfredo Geniola, Anna Maria Tunzi – “Cultural and artistic expressions in the Cave of Cala Scizzo, near Torre a Mare (Bari)” – 1980 – into Journal of Prehistoric Sciences – XXXV - 1-2 - pp. 125-146;

- Marija Gimbutas – The language of the Goddess – Ed. Venexia – 2008;

- Paolo Graziosi – Prehistory in Italy – 2 volumes – Sansoni (Florence) – 1973;

- Maria Laura Leone – “The ideology of the menhir-statues and stele-statues in Puglia, and the conceptuality of the phallic-anthropomorphic symbol” – 2000 – into Notebooks of the Lombard Archaeological Association – pp. 119-145. Milan;

- Maria Laura Leone – “Philosophy of the afterlife in the Apulian Paleolithic” – 2006 – into Hypogea – notebooks of the IISS “S. Staffa” of Trinitapoli – December 2006 – n.1 – pp. 83-92;

- Maria Laura Leone The Phosphenic Deer Cave. Art, Mythology and Religion of the painters of Porto Badisco – Ed. l'Espresso (Rome) – 2009;

- Maria Laura Leone – “Feminine messages from the prehistory of art. The artists of Grotta Chauvet and Grotta dei Cervi” – 2015 – into Proceedings of the Conference “Marija Gimbutas. Twenty Years of Goddess Studies" – Rome 9-10 May 2014 – pp. 145-157 – Italy;

- Maximilian Mayer – The prehistoric stations of Molfetta. Report on the excavations carried out in 1901 - Bari 1904;

- Frances Radina – Nature, archeology and history of Pulo di Molfetta – Adda (Bari) 2007;

- Catherine Schwab – The Piette Collection. National Archeological Museum of Saint Germain en Laye – Paris – 2008;

- Rodolfo Striccoli – Prehistoric cultures of Grotta Pacelli – Castellana-Grotte – Ed. Schena – 1988;

- Alessandra de Nardis – The Gravettian cap – Pescara, 2021.