di Maria Laura Leone

write on Cave of the Deers of Porto Badisco in Salento is stimulating and arduous. The artistic complexity and the anthropological phenomenon that characterize it involve science, philosophy and neurology at the same time. It is a singular place and dealing with it, as with my excursus linked to it, leads us to rationalize emotions that have existed since I entered it the first time. It was February 1983, XNUMX thirteen years after its discovery and I knew nothing of this anniversary, as of what I would see inside. Everything about the special cave was unknown to me. I was in the first year of university studies in Lecce and had recently attended the lessons of Emmanuel Anati, then full professor of palethnology. The professor spoke to us about prehistoric art, millennia of conceptual evolution and Australian aborigines; parallel to his lessons, his assistant Elettra Ingravallo was responsible for instructing us on the material culture of flint and ceramics. It was Anati who organized a visit to the cave, he had recently held a lesson on the paintings in the cave but for a fortuitous reason I hadn't participated in it and when the day of the visit arrived, I barely managed to get on the vehicle risking losing one of the most touching experiences I would have had. Once we got there, total ignorance worked in my favor. The amazement of that first descent left a furrow in my future as an archaeologist, and beyond.

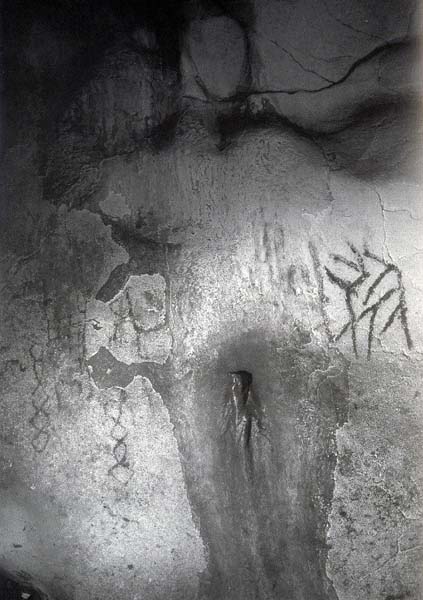

After a short descent on a pair of rusty ladders and a low, narrow tunnel thirty meters long, we found ourselves in a large hall in which we were shown the three entrances to the other painted corridors. The magic of the place was already felt in that sector, the same as in the book The phosphenic Grotta dei Cervi. Art, mythology and religion of the painters of Porto Badisco published in 2009, I would have named "the red hall”. In some places the darkness revealed some ocher scenes as beautiful as they were incomprehensible, but only in the rest of the cave would we have seen the typical brown abstraction painted with bat guano. In this abstraction very few figures were recognizable, for example slender characters frozen in the gesture of an unusual hunt, but the bizarre designs were everywhere; then they disappeared into the dark. Wherever the gaze rested, the walls housed glimpses and streaks of colour, swirls of material paint, beings with a bewildered body surrounded by imprecise geometries: spirals, concentric circles, dots, labyrinths and together with all this also deer, but designed as strange stark creatures in a string toy pose. They too were surrounded by geometric figures and the latter were often inside other strange hybrid creatures: a man in the shape of a labyrinth, a woman made up of spirals, another woman in the shape of an "ESS" and with coiled limbs like snakes .

Faced with so much bizarreness, I wondered who ever wanted such an unusual "museum", hidden from the eyes of the world. I asked this to the professor who invited me not to speak but to observe and reflect. His words justified my wanting to stay at the rear of the group to contemplate the suggestions of that unusual experience alone and as I looked at the paintings on the undulations of the rock, I thought how lucky I was; that place suited me. The silence, its darkness were not only enveloping and welcoming but instilled an incomparable charm. Slowly, almost fearful and cautious, we advanced with torches as far as the last room and before reaching it, under a passage that precedes one of the densest points of paint, I noticed that the wall formed a great monstrous face; it was at the top and seemed to be the "guardian" of the rooms that extended towards the end of the corridor.

I pointed out that face to Anati, but he smiled at me and didn't add anything: I shyly withdrew and photographed it. That photo was the first document that stimulated my interest in pareidolia in prehistory[1]. Years later the same professor discovered an anthropomorphic of incredible realism, incorporated into the natural form of the wall[2].

The new room, beyond the stone face, was narrow and long, with the wall to the right covered with brown designs, almost all impenetrable. In the center of the room, just in front of the painting of a giant insect, dominated a stalagmite. Then, further on, the paintings stopped and a section with stalagmites and stalactites began, near a pool of water. After that, the black-brown miracle of the drawings reappeared and this time they were among the most beautiful and preserved; a theory of geometrized characters ran on an imaginary papyrus roll, to arrive near the arch-shaped entrance of the penultimate room, the most sacred, the one called "the Sanctuary”. After going through this first corridor, almost two hundred meters long, we turned around and took a side branch also full of paintings; the most labyrinthine and the most faded. Even our path seemed labyrinthine to us and the dominant sensation was that without a guide we could never see the light of the sun again. The drawings on the rock seemed to reproduce this topographic status exactly, it was not clear where we were, which passages we had already crossed or where the exits were. At any rate, I don't think any of us had the desire to leave the cave anytime soon. That desire, still not weakened today, aroused in me the desire to undertake studies of prehistoric art and visit other similar places. Without knowing it, I had received my initiation into cognitive archeology in that cave.

A book for an etiology of the artistic phenomenon

After that time I entered the cave other times, but it was in the XNUMXs that I spent three days in a row from morning to night and formulated an etiological hypothesis about its strange art. In walking the wide corridors, crawling along the short bottlenecks, sensing the strengths, two entrances and a connection area between three branches, observing the undulating walls that recreated attractive faces and shapes; I understood that the cave was a revealing place, where pareidolia also played an important role. It was an ideal place to foster those ideational mechanisms of making "art". In the aforementioned book, I explain the psychedelic etiology of these mechanisms, as well as the semantic evolution of the paintings. These paintings, which at first glance seem childish scribbles, mere actions intent on smearing the milk-colored walls, hide sensory explosions experienced in the geological womb and are shown on the walls as evidence of a powerful neurological-cultural experience. This "belly" had to be understood both as a generator and as a custodian of the neuro-pictorial phenomenon. Within it arose a journey capable of letting emerge phosphenic apparitions and visions seen with one's own eyes, experienced on one's skin and felt in one's body. The paintings would also, but not only, be the description of what the artists felt during hypersensitive experiences and testify to their communication-interaction with a supernatural world, interpreted according to their own mythological and spiritual culture. The deer hunt, represented several times, seems to be the main metaphor of that psychedelic journey destined for the encounter with the phosphenic abstractions, with the creatures and energies of the Elsewhere of the Badischiani.

A contemporary reference to this metaphorical mechanism is in the shamanic art of the Mexican Huicholes, in which the deer and the peyote are closely matched and even identified with each other[3]. In fact, anthropomorphic, phosphenic and geometric-abstract figures such as those of Grotta dei Cervi are widespread throughout the world, occupy various chronological horizons and seem to derive from a common area: the psychoactive exercises practiced by shamans. In this regard, the neurological and anthropological studies carried out on the phosphenes in the seventies of the last century revealed that the tribal populations devoted to the use of psychoactive substances associated the phosphenic forms, like the same visions, with their artistic expressions and their interpretive thinking. The Tukano people of Colombia studied by Reichel-Dolmatoff[4], was a champion in these researches and, subsequently, also the paintings of the rock shelters of Chumash, in California, were understood as of phosphenic origin[5].

I arrived at the literature of phosphenes, also defined as entoptic phenomena seen in absolute darkness, thanks to Giorgio Samorini, who had contacted me for a review of my publication on the study of the opium poppy inherent in the Stele Daunie[6].

The knowledge of the phosphenes and the discovery of these mental mechanisms led me to formulate the presence of entoptic phenomena also in the art of Porto Badisco and, consequently, to identify those semantic and cognitive processes that can lead us to an understanding of certain graphemes . Semantics is the first and perhaps the only step to approach cognitive and spiritual behaviors in prehistory and the phosphenes are the building blocks of Badisco's pictorial semantics. The pitch dark of the cave may have contributed to generating the fascinating phosphenic forms, only in this way can those bodily transformations, those remotely realistic forms, be explained. There is no other procedure that can help us understand these graphic expressions which in the Badischiani culture must have been significant and symbolic for centuries and perhaps for millennia.

Along with darkness, a sure phosphene stimulant, the managers of the underground cult may have used psychoactive substances. In this regard, I believe that the abundant guano, present on the paleosoil, may have been exploited as a fertilizer for the cultivation of hallucinogenic agents such as psychoactive mushrooms and that, in theory, the tradition of such agents was in the ancient culture of cave-goers. Analyzes conducted on the organic residues of pottery found in a cult area in the village of Porto Russo, dating back to the Bronze Age 1500-1400 BC. C. and located just 400 m from Grotta dei Cervi, have shown traces of an alkaloid present in both castor and ergo. Excluding the widespread presence of castor oil, at that time, the authors of the study lean towards the matrix of ergot and hypothesize that alcoholic and psychoactive substances were used in the area of worship for sacramental purposes[7]. It is well known that ergotamine, the LSD alkaloid discovered by the chemist Albert Hofmann, is also the best psychoactive candidate in the recipe for ciceone, used in the Eleusinian mysteries together with opium. Ears of corn and opium poppy are, in fact, the two sacred plants that Demeter eludes holds in her hands, in a clear hiero-botanical symbology[8].

In the book indicated above, I also explain that the figures were painted as they appeared to the eyes of the experimenters, i.e. in motion. This is one of the reasons why they are tangled, multiplied and superimposed and, therefore, must be untangled as one does with a skein, if one wants to understand them. I also explain why the deer is an animal associated with a hunter accompanied by two dogs, or that in the same cave another animal is painted, perhaps more important than the deer, rendered through the grapheme of the "ESSE" and corresponding to a snake. It is also a hierophant animal, as it is associated with the phosphenes, but it is also connected to the sacred feminine, as it transpires in the representations of the Great Mother. In the Salento cave dwell symbols now female, now male and it is understood that the two animals, despite having specific roles, allude and participate together in metamorphic magic. It would not be improper to rename the site as: the "Cave of the Deer and the Serpent”. At the time of the Grotta dei Cervi paintings, between the Middle Neolithic and the beginning of the Copper Age, the underground was symbolically linked to the deer and the snake, but I also recognized traces or embryos of entities known as: the forked siren, Cernunnos, Hermes runner, the Androgen. Evidently the culture of the time already contained the matrixes of entities which, centuries later, would become canonical and, today, the cave reveals itself as a treasure chest of mythogenesis.

In Badisco's basement many ceramics were also found which testify to the performance of innumerable ritual practices, but the paintings remain the most emblematic datum of what took place in darkness, an important darkness, perhaps even hidden in the toponym of Badisco. My idea is that the word Badisco is the last "linguistic" memory of the existence of the underground and its profound darkness. It is deducible that the term I mind has a Greek matrix in βάθύσχόιος. The term is formed by a prefix βαθύς, adjective of deep and a suffix σχόιος (–ά -ον [ςχία] [ςχότος]), adjective of shady, dark, gloomy, and it would mean deeply shady: of deep darkness. But the interesting thing is that βάθύσχιος does not indicate a cavity as such, otherwise definable with άντρον (cave) or σπήλαιον (cavern) but defines an obviously mysterious, impenetrable and even disturbing place, because ςχία stands for shadow of people or things, But also deceased (ghost, ghost) and ςχότος stands for dark, gloom, darkness of death (in Aeschylus) e afterlife (in Sophocles)[9].

At the conclusion of this retracing, I would like to recall Isidoro Mattioli, a figure inseparable from Grotta dei Cervi. One of the discovering cavers. With him, moved by a great passion for the cave, I wove arguments on its possible meaning. And I won't be able to forget the last time I saw him during a descent in 2002. Traveling down the cavity together was almost ancestral; it seemed that Isidoro had lived down there for a lifetime. Four years later he disappeared, kidnapped by an incurable disease.

In all these years, many people have asked me why Grotta dei Cervi is not open to the public. I replied that everyone should see her in the right way, to learn from her singularity, to grasp the value of a past existence that belongs to us and must be understood, but I have always added that her safety is sacred and must be protected. Today, advanced reproduction systems could allow remote use, but fragility will remain its weak point. Fifty years after their discovery, the paintings are already deteriorating and if this process is not stopped or slowed down, the cave will lose the prodigy of its rarity. Even the so-called "Port of Aeneas", a popular name for Porto Badisco, must be protected. Every summer more and more bathers arrive and the traffic engulfs the road which, before reaching the sea, passes over one of the last painted rooms. And right below, in the most recondite space of the central corridor, one of the most emblematic "graphic phrases" is painted.

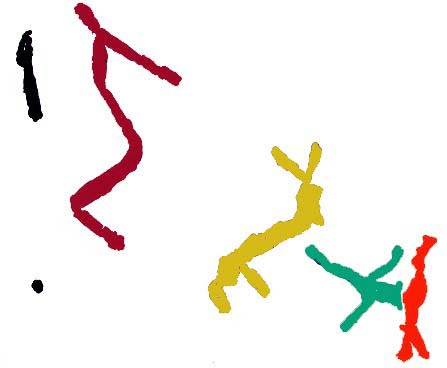

A hunter (right) aims a bow and arrow at an anthropomorphic deer and, symbolically, activates a psychoactive state in a character who flies away (left). The dot and dash are indicators of the action that is taking place.

The story of a metamorphosis in which a hunter aims a bow and arrow at an anthropomorphic deer and, symbolically, activates a psychoactive state in a character who flies away to elsewhere.

Maria Laura Leone – January 2021 (text extracted from a forthcoming volume by Giancarlo Sani)

Footnotes

[1] Maria Laura Leone – “Life in stones and images. Pareidolia and kinetics, two interpretative procedures in prehistoric art” – in Institute notebooks “M. Dell'Aquila" – San Ferdinando di Puglia 2014 – pp. 75-83;

[2]Emmanuel Anati - "The cave-sanctuary of Porto Badisco" - in utility bill Camuno Center St. Preist. - Vol. 34 - 2003 – p. 106-124;

[3]Maria Laura Leone The phosphenic Grotta dei Cervi. Art, mythology and religion of the painters of Porto Badisco – 2009 – p. 22-25;

[4]Gerard Reichel-Dolmatoff – The Shaman and the Jaguar. A Study of Narcotic Drugs Among the Indians of Colombia. – (Temple University Press) Philadelphia 1975;

[5]Ken Hedges – “Patterned Body Anthropomorphs and the Concept of Phosphenes in Rock Art” – in Rock Art Papers – Volume 4 – San Diego Museum Papers 23 – 1987 – pp. 17-32;

[6]by Giorgio Samorini review appeared on ELEUSIS Information periodical Italian Society for the study of States of Consciousness – n.3 – pp. 42-42 – December 1995 – for the article: “Opium. “Papaver Somniferum” the plant sacred to the Dauni of the stelae” – in bills. Camuno Center St. Preist. - vol. 28 – pp. 57-68 - 1995. See also the text

[7]Giorgia Aprile, Florinda Notarstefano and Ida Tiberi – “Indicators of cult practices in the Bronze Age fortified site of Porto Russo (Otranto-Le)” – in Antiquity Studies - 14 - 2016 - p. 5-25;

[8]For a comprehensive overview of this research, see the text;

[9]Franco Montanari – Vocabulary of the Greek language. (Loesher) Turin - 2004 - pp. 1931-1935.