di Alessandra de Nardis

Prehistory is certainly an inexhaustible place of questions that are unlikely to ever find answers. When we try to reconstruct our origins, intuition remains perhaps the only useful faculty since it draws on the deepest and most recondite ancestral memories.

Despite the scarcity of artifacts created by our ancestors left intact by time, there is one that has been found recognizable on several occasions thanks to the materials of which it is made.

We are talking about a particular object present in several gravettian burials (upper Paleolithic around 29.000 to 20.000 years ago), almost always belonging to female individuals; a kind of "cap" composed of small intertwined shells of the genres Nassa neritea, Trivia or Columbella, to which red deer canines are sometimes inserted; the whole is finely knotted to form a sort of headgear covered in red ocher and found to cover the skull of the buried person; we do not know if this object was also brought to life but we also find similar representations on the heads of many statuettes belonging to the same era, the so-called Venuses, for the rest of the body naked.

The object itself may appear as a simple recurring particularity, an embellishment of the person, a sign of lineage or a ritual to be associated with specific individuals of the community at the time of their passing away; What if it represents something more significant?

We are used to thinking that precious objects belong to certain classes and denote the social superiority of the person who wears them; is it therefore possible that 29,000 years ago there was already a categorization of classes within human groups? Some academic studies such as that of Dr. Francesco d'Errico of the CNRS the Scientific Research National Center – Social inequality in the Upper Paleolithic: personal ornaments of Saint-Germain-la-Riviere (Gironde, France) – they claim just that.

Here we are unable to imagine anything different from our past that is other than what we are today.

The film Signs out of time by Donna Read and Starhawk, a tribute to Marija Gimbutas who reconstructs her vision of a civilization prior to the historical ones asks us: “What image do we have of our past and how does it influence who we are and how we live? Are we capable of imagining a peaceful culture in harmony with nature? Was there ever one?"

Asking these questions allows us to change the approach to the study of our origins and with it the possibility of seeing other possibilities.

Why not imagine that this coif was a symbol of what these women (and men) represented to the community that buried them with such honor? A sign not necessarily linked to power as we understand it but to the sacredness of its meaning. And proof of this in my opinion is the fact that these objects were found almost exclusively worn by women and often mothers.

Does it seem so absurd to us today?

In Italy we can compare at least four of these objects in as many burials belonging to three women and a man; let's talk about Woman of Paglicci, Woman of Caviglione, Woman of Ostuni and the so-called Prince of Arene Candide. In common these human beings had the same period and the same culture: the Gravettian and, of course, also the "headset".

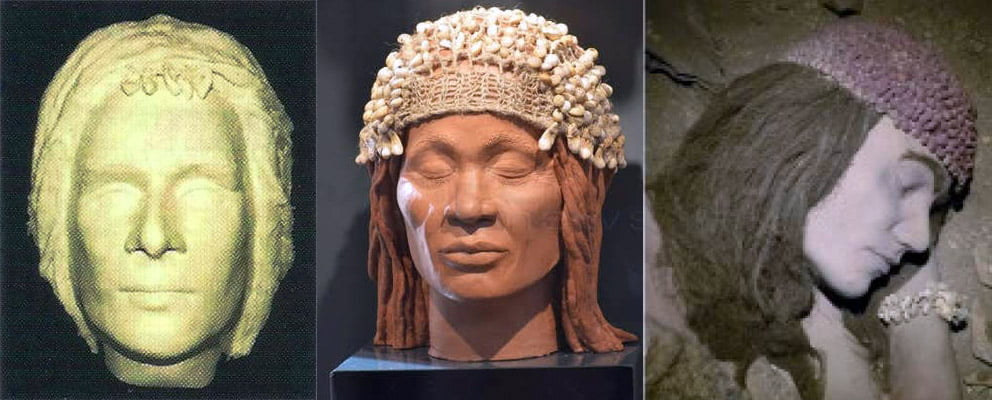

[Pictured, from left:

La Woman of Paglicci, in the Paglicci Cave Museum in Rignano Garganico (FG), Puglia, dating: 23 years ago

La Woman of Caviglione, (until recently called the man of Mentone then following the DNA test attributed to a female individual) at the Balzi Rossi Prehistoric Museum (IM), Liguria, dated 24 thousand years ago;

La Woman of Ostuni, called Delia by its discoverer, in the archaeological and naturalistic park of Santa Maria D'Agnano, a few kilometers from Ostuni (LE), Puglia, dated about 25.000 years.]

[Pictured: the Prince of Arene Candide it is the skeleton of a 15-year-old boy discovered in Arene Candide, he owes the nickname "Prince" to the extraordinary equipment with which he was buried; his head is surrounded by the "bonnet" made up of hundreds of perforated shells. Discovered in the Arene Candide Cave in Finale Ligure (SV), Liguria, dating back to about 26000 years ago.

1.70 m tall, he has very strong arms and legs trained by continuous and prolonged efforts.

The analyzes done on his bones tell us that he ate a lot of wild animal meat, but also fish and molluscs.

The body lying down and covered in red ocher, the kit is very rich with objects in shell and mammoth ivory, as can be seen on the first floor of the museum.]

La Woman of Paglicci it was unearthed in 1989; the remains of this young woman became the most archaic human testimony in Europe. The cave discovered in the 50s is located in Puglia and is the most important in the Gargano and among the most important in Europe for the quantity and type of finds found: over forty thousand lithic tools, human skeletons, paintings, graffiti, flori-faunistic remains referring to the three phases of the Paleolithic - lower, middle and upper - currently exhibited in the Museum of Rignano Garganico. The cave also contains some Paleolithic wall paintings depicting horses, goats, cows, a snake, a nest with eggs, handprints and a hunting scene engraved on bone. Archaeologists also uncovered evidence of Paleolithic oat harvesting dating back to 30.600 BC from a pestle recovered inside the cave concluding that our ancestors ate oatmeal long before the advent of agriculture.

La Woman of Caviglione she is a mother who lived approx 24 thousand years ago. It was found on March 26, 1872 during the excavations led by Emile Riviere in the Caviglione cave, part of the Balzi Rossi archaeological site, on the Italian-French border of Ventimiglia; the excavations unearthed a burial of what until recently was called "the Man of Menton". It was only following the DNA examination that the skeleton was revealed to belong to a 37-year-old woman of very tall stature and who must have borne her children; The find was transferred to Paris where it is kept in theInstitut de Paleontologie Humaine, the mold remains at the Balzi Rossi. The burial in the description is characterized by a cap formed by shells and deer teeth and a set of horse bones.

In 1991 in a cave in the archaeological and naturalistic park a few kilometers from Ostuni, Delia was discovered, the woman of Ostuni; a skeleton, dating from approx 28.000 years ago of a twenty-year-old pregnant woman, found with her right hand resting on her belly. The find is kept in the Museum of Pre-Classical Civilizations of Southern Murgia.

The woman, in the terminal state of her pregnancy, had been laid inside the chasm that opens up on the slopes of the hill overlooking Ostuni. The cave, later renamed "of motherhood", shows traces of stratified uses and cults that lasted from the upper Paleolithic until the seventeenth century. It was found that the woman lived between 27.810 and 27.430 years ago.

The body composed with great care was adorned with jewels and some pierced shells were found near the right wrist, certainly what remains of a bracelet and a set of stone tools. The head was adorned with a cap dyed red ocher and composed of shells, probably of the same type Columbella rustica and deer teeth. Other teeth, this time from horses and cattle, were found near the body.

Also in France we find documented the same type of burial; the skull of a woman with traces of a "bonnet" made with shell weaving and covered with ocher; the photo shows the reconstruction of the face of a female human skeleton found a Cap Blanc shelter in the municipality of Marquay east of Les Eyzies, discovered in 1909; it is a prehistoric rock shelter from the Magdalenian era between 17.000 and 12.000 years ago, therefore more recent than the Italian ones; the skeleton was exhumed at the base of the shelter wall. He was lying on his left side in a fetal position, one hand on his face. The body was placed under three stone slabs: today it has been replaced by a copy of the original which has been in the Field Museum of Chicago since 1926. The shelter is characterized by its enormous bas-relief sculpture depicting various animals: bison, ibex , bears, reindeer, other animals sometimes difficult to identify and lots of horses.

Also many figurines of which many from France seem to wear the same type of cap; the period is the same as for the burials.

[Pictured, from left:

The Lady of Amiens, found in Renancourt, near Amiens, in northern France – Upper Upper Paleolithic (about 23.000 years old).

The Lady of Willendorf, Austria (23.000-19.000 years);

The Lady of Brassempouy (27000 years old) called precisely "dame a la capuche".]

An astonishing peculiarity of these statuettes is represented precisely by the grid of thin incisions that we find and which seem to represent the same type of woven headdress found in the burials; can we therefore imagine that such an object was a sort of symbol and, above all referring to the statuettes, a sign of the Goddess? Can we imagine that whoever wore that cap covered the role of priestess (or priest) and that used for her burial a propitiatory object for her rebirth?

In short, we wonder if this "cap" more than a simple ornament can represent the origin of what in less remote times was attributed to sacred objects, artifacts capable of putting a human being in communion with the divine and thus becoming the protector of the whole community.

Masks, hats, disguises become "magical" objects, symbols of intercession with "another world" and their origin is lost in the mists of time; artifacts capable of making the wearer mediators thanks to which the community came into contact with "the ground below". The person was what in all cultures is defined as shaman, the one (or the one) capable of moving and being in contact in otherwise inaccessible spaces.

We have in our era an element similar to the one just described and which, like everything that is visible to all, becomes invisible; the saints, whose protection for people and places we invoke and who are represented with the symbol on the head of their "communion" with god, play the same role.

Finding the image of our patron saint with a halo around his head, an archaeologist of the future would undoubtedly assume that the individual buried with such honor had been some prince or king.

And that would be a completely erroneous point of view.

Alessandra de Nardis – 25 January 2021