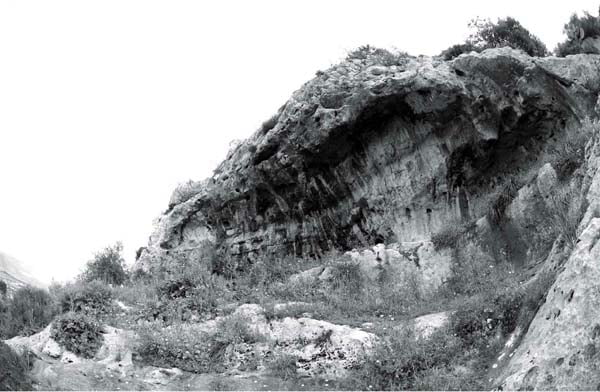

The vast rock shelter of San Giovanni takes its name from a district where a small church dedicated to the saint stands, a few kilometers south of Sambuca di Sicilia. The set of cavities is located at the foot of a rocky ridge - onto which several ravines and a cave open - on the south-western slopes of Cozzo Don Paolo. The entrance is exposed to the west in the direction of Lake Arancio, which is about a kilometer away.

The most interesting shelter is the second one on the ridge wall (starting from left to right, shelter A/Riportella), of considerable size (about 5 meters high and about 12,50 meters wide), whose back wall, slightly arched and polished by the fleece of animals for a height of about one meter, it is affected by a very rich series of over 400 vertical and geometric linear incisions, different from each other both in length (the dimensions vary between 48 and 2 cm) and for engraving marking.

The linear element is one of the most recurring graphemes in the context of Mediterranean wall manifestations between the late Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The groupings of engraved lines, generally vertical, are found in numerous Sicilian caves, and are widespread both in Europe and in the Mediterranean and in North Africa. “Particularly interesting are the comparisons with the so-called traits capsiens engraved on stones or on the walls of North African shelters dated to the Neolithic of the Capsian tradition. This last comparison assumes particular importance if it is related to the possible existence of contacts between Algerian-Tunisian northern Africa and Sicily during the Mesolithic" (Buccellato et al.)

The Sambuca complex is the richest so far found in Italy and perhaps in the entire Mediterranean; given its characteristics, it does not seem to have had a residential function, rather it seems a place used for symbolic functions of a sacral type, a meeting place for the community of the area, in the period between the Epigravettian and the Mesolithic. The linear elements, while not showing an order,"sometimes they give the impression of being grouped into groups characterized by similarities in the incidence of the sulcus" and clearly show that they are a strongly unitary whole (Tusa).

At the base of the rock wall on which the linear incisions insist, on a slight horizontal overhang that is located a few centimeters above the walking surface to form a sort of seat along the entire wall, "we find an anomaly with respect to the majority of Sicilian linear engravings, namely the presence of isosceles triangles and above all, more than elsewhere, pairs of lines converging downwards which sometimes come to intersect forming triangular figures”, considered vulvar figures (Mannino, 2017).

Symbolic representations of the female pubis in the shape of a V, a triangle or chevron they have crystallized since the upper Paleolithic, engraved in caves or carved on objects in bone or ivory.

In shelter B/Riportella, flanked to the previous one, at human height, the rock is covered by a layer of "orange peel" calcareous concretion on which, in a vertical direction, a reddish halo with brown and brighter red features can be observed. It is probably a two-tone image, brown and red ocher, made evanescent due to exposure to atmospheric agents: alongside anthropomorphic figures stylized in red, we find "tree-like figures in chains" of dubious meaning.

The figurative manifestations of shelters A and B seem to date back to different periods and have different purposes.

A couple of meters below we find the cave of San Giovanni, whose entrance is closed off by a dry stone wall. The internal environment has an almost circular shape (about 12 meters in diameter and 4 meters in height), with luxuriant vegetation fed by a small pool of water gushing from the bottom of the cave. According to Mannino, some small niches are carved out of the wall, probably used for votives or oil lamps. The humid environment prevented stable residential use, but probably not ritual use.

In the area surrounding the shelters, abundant lithic industry seems to have been recovered including burins, disc-shaped scrapers, back blades, geometrics and micro-burins which refer to aspects of the evolved-final Epigravettian, and several pebbles with engraved zoomorphic representations (equids, bovids, cervids, swine, goats, sheep and perhaps a rabbit), in some cases in scenes perhaps referable to hunting; in one of the graffitied pebbles there would be incisions "that can be cataloged in the context of vulvar symbology" (Riportella).

A short distance from the site, to the south, the remains of huts and scattered Neolithic pottery have been found. This data is of great importance above all from the point of view of the topographical organization: the rock complex, on the hydrographic left of the valley, could be considered not only a community meeting place of a sacral type (Buccellato et al. hypothesize that the shelter could have been a "pilgrimage" destination, in which part of the ritual could include drawing a line on the "sacred" wall), but also the site of an important atelier for the production of lithic industry, such as the enormous quantity of nuclei flint seems to indicate.

The linear incisions, found in numerous archaeological sites, still have an enigmatic meaning today: they have been interpreted as a method of calculation or reminder in a form analogous to the marques de chasse (signs of hunting), or as a product of propitiation rituals for hunting; as marks for a calendar; as an extreme symbolic stylization of the human figure: the hypotheses are still open.

According to Leroi-Gourhan, engraved series of this type could also represent the intention of a repetition and, consequently, a rhythm: these first human evidences of rhythmic expression are found in fragments of bone or stone, with incisions at intervals regular and equidistant bearing witness to the very origin of the figuration. They would be evidence of the most ancient rhythmic manifestations that have been expressed, even before the forms, which appeared at the same time as the dyes (ochre and manganese) and the first ornamental objects.

A rhythmic gesture is both the performative gesture (danced or percussive), and the gesture for the production of tools (handkerchiefs, choppers or other objects that arise from beating, sawing, hammering or scraping stone or wood to transform their shape) or – in this case – for the production of signs.

"From the outset, the manufacturing techniques were placed in an environment of rhythms, at once muscular, auditory and visual, derived from the repetition of gestures […]. To the shuffling, which constitutes the rhythmic framework of the march, is added, in the human being, the rhythmic animation of the arm; while the patter regulates the spatiotemporal integration and is at the origin of animation in the social field, the rhythmic movement of the arm opens up another outlet, that of an integration of the individual into a system that no longer creates space and time, but of shapes” such as linear incisions or calendar signs (Leroi-Gourhan, 1977: 362). According to the scholar, since their first appearance, the series of traits have been associated with female symbols. The rhythmic signs seem to precede the clear-cut figures, which integrate with them by superimposition, as if it were a single context made gradually clearer by the visual symbols. The explicit forms found in archaeological research are initially female ovals or vulvar symbols (the women represented in a complete way will come later) which can be associated with the heads or front parts of shapeless animals. In all the well-preserved ensembles the figures are systematically grouped: rhythmic-vulva-animal signs.

However, the presence of the water resurgence and the niches on the wall of the cave of San Giovanni leads us to add further considerations. The cult linked to the sacredness of the waters is among the oldest ever, and is always associated with sacred female entities; Gimbutas believes that the association between the sacred feminine and waters has existed since the Paleolithic; many Paleolithic and Neolithic sanctuaries were located in caves where there were sources of water (both mineral and thermal). “Streams in the shape of comets, or diagonal parallel lines, vertical or in bands of meanders, are frequent motifs in the furnishings and in the art of the Paleolithic and Mesolithic”. According to the researcher, these shapes would indicate the presence of a water current: watercourses in the form of lines and groups of parallel lines would recur very frequently in prehistoric art up to the Neolithic.

The coexistence of the water source with the votive niches and the vulvar symbolism of the shelter next to the cave make this hypothesis plausible. On the other hand, the cult of the sacred feminine linked to the waters has a very long persistence in Sicily.

"Sicily is also a karst and volcanic land, that is, it has an enormous quantity of underground cavities dug out by the water (springs and resurgences, scrambled or underground rivers, gorges) but also shaped by volcanic fire. At the points where the two elements (Nesti and Aidoneo) meet, their union gives rise to hot or sulphurous water springs with different properties, or other extra-ordinary phenomena such as mud volcanoes, maccalube etc.; the properties of hot or sulphurous waters were known since ancient times: curative properties but also psychotropic, when not toxic, which gave them a sacred character. The openings towards the subsoil from which vapors or thermal and sulphurous waters emerge, and all the real volcanic emergencies such as Etna, Vulcano, Stromboli, are all considered direct access doors to a world otherwise forbidden to the living: Hades.

Equally powerful places are the caves from which springs of perennial waters arise, chthonic essence that comes from the belly of Gea, and the places from which they flow are also points of contact between ours and the underworld. Water is a sacred element, and is linked to life, death, birth and ritual re-birth.

All of us, before birth, spend the nine liminal months of gestation in water. Just as the menstrual cycle is concretely and symbolically linked to the cycle of the moon, the 'breaking of the waters' at the time of childbirth has symbolically connected the female body with the body of the Earth, giving rise to the cult linked to the waters gushing out of the cave: the Nymphs, as beings who inhabit – and who guard – this aqueous border between the Worlds, they are patroness of springs and fountains (even of warm waters); the nymphal deities therefore preside over the births, they are similar to the Maie, the midwives, and at the same time they act as guides in the female rites of passage which foresee a real or ritual death and rebirth (menarche, wedding, pregnancy, childbirth, death). If the observation and study of the rhythms of menstruation, pregnancy and childbirth have been at the root of our ability to abstract and symbolize (as the Palaeolithic and Neolithic archaeological finds seem to testify), it is not surprising to find this increasingly complex symbology – index of long-lasting reflections and semanticizations – within uterine metaphors (caves, doors, passages between Worlds) even in the historical age” (Crescimanno, 2020).

Historical notes

The discovery of the site was carried out in 1986 by Rocco Riportella, on the recommendation of Vito Gandolfo, a scholar of the area, and was presented at the XI UISPP congress in Mainz (Germany) in 1987 by Gerlando Bianchini, president of the Sicilian Center for Prehistoric and Protohistoric Studies of Agrigento. In the file, to distinguish the various cavities of the site, the criterion of the discoverers was used: shelter A is considered the one with graffiti, shelter B the one with paintings and the letter C the adjacent cave.

CARD

LATEST PUBLISHED TEXTS

VISIT THE FACTSHEETS BY OBJECT