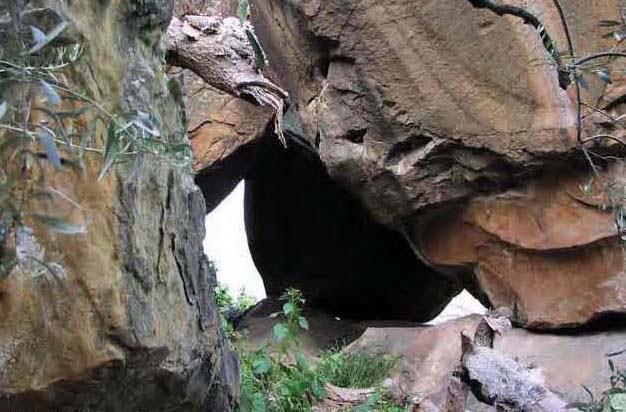

The "shelter under the rock" is located in the Centuripe area (Enna), in the Picone district, on the right bank of the Simeto river, just 2 km from the Stentinellian necropolis of Fontanazza, on the opposite bank of the river (see fig. 1).

The definition of "shelter" is inaccurate: the place, in fact, does not protect against atmospheric agents; the upper part has an opening large enough to allow observation of the sky, and is exposed to the winds from three sides; due to the characteristics of the place and the findings it seems to suggest, rather, a place of worship.

The walls of the shelter are massive sandstone boulders, collapsed and leaning against each other to form various ravines, which would almost seem, due to their dolmenic appearance, arranged by human hands; for the floor - partially - another block of sandstone flattened and smoothed by the erosion of the river in ancient times; along one wall of the shelter (the one in front of the pictorial complex we are about to describe) there is a natural quay.

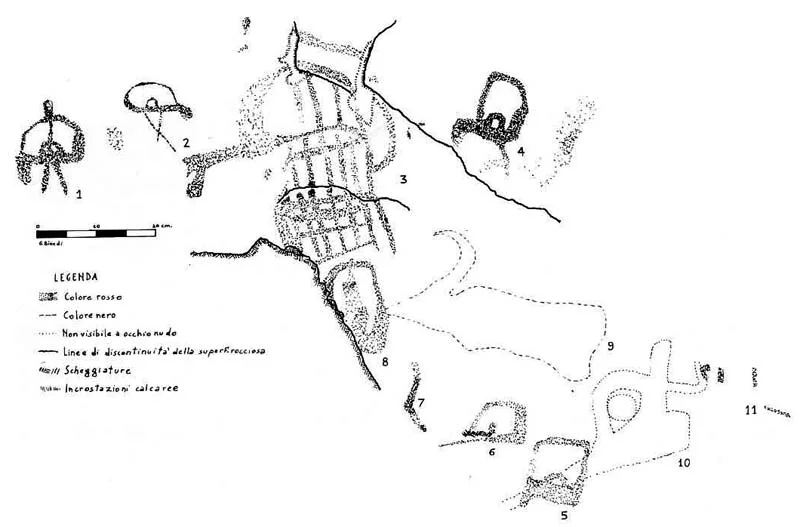

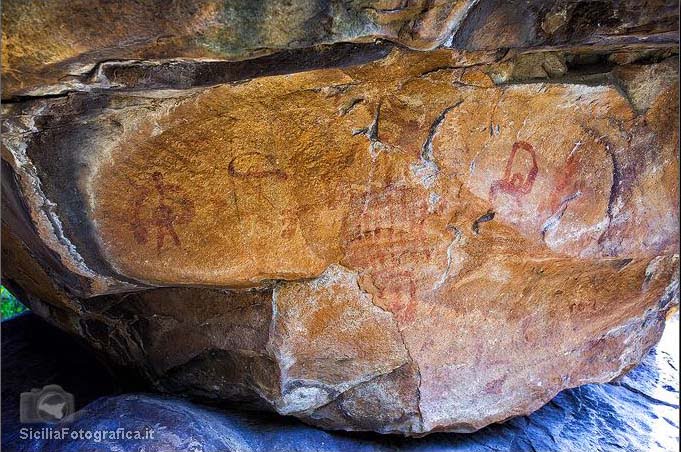

On the main wall numerous paintings can be distinguished, the only ones so far documented in eastern Sicily. Being practically outdoors and a few meters from that natural communication route which was the Simeto, the paintings "they had to be accessible to all communities scattered along the river, and a central point of reference for them” (G. Biondi, 2017). The pictorial complex is made up of two distinct groups (see fig. 2).

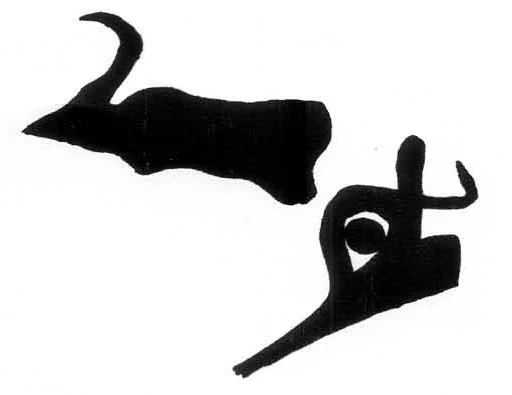

The first group, which appears to be the oldest, is made up of two figures in black paint, now almost evanescent and made visible only by infrared photography (see fig. 3).

The first is a bovid with a long curved horn, which recalls - in terms of style and chronology - the bovids of theAddaura, expressions of the art of the Late Paleolithic, or those of the Cave of Cala dei Genovesi in Levanzo, or again the Bovidian-style rock paintings of northern Africa (G. Biondi, 2002). The Cassataro ox can be generically classified in a stylistic phase of the end of the Paleolithic.

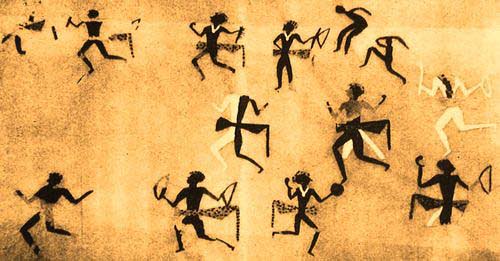

The second is an anthropomorphic figure that seems to be in a dance position, with a small round object held by its side under one arm, probably a drum; this figure, and the proposed identification, have been compared with a similar round object, portrayed in the hand of one of the characters in the "frescoes" of Çatal Hüyük, in Anatolia (see Fig. 4).

"The accentuated schematism, to which is added a strong sense of dynamism, makes this element distinctly different, from a stylistic point of view, from the previous one and brings it closer to post-Paleolithic figurative expressions” (G. Biondi, 2002).

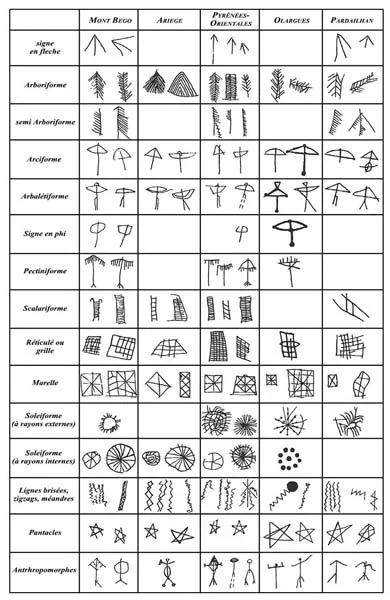

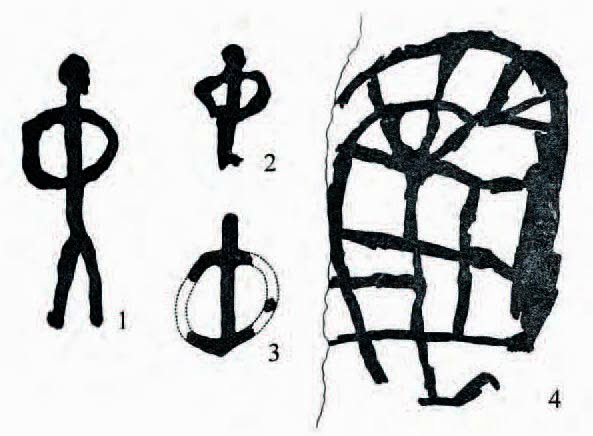

The second group (see fig. 5), which partially covers the first and is therefore probably later, is made up of numerous figures in red ocher (hematite and other minerals, rich in iron oxide), which we can stylistically date to the Neolithic; in a fairly central position in the composition there is a "reticular" figure (figure no. 3 of the second image) with vertical and horizontal lines, which can be compared with similar examples of other recurring reticles in prehistoric art, interpreted in various ways: the schematic representation of a flock, or of the "idoliforms" (see fig. 6).

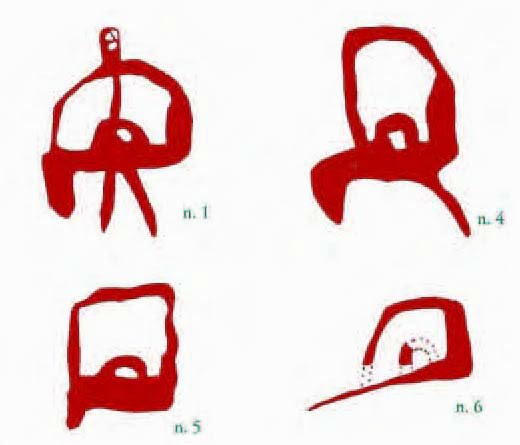

Around this appear a series of figures of uncertain reading, but which have been interpreted as anthropomorphic (see fig. 7); in reality only the first from the left (n. 1 of the images) is immediately recognizable as a human being, albeit schematically rendered, in a style that can be compared with some cave paintings found in Spain (see fig. 8) and in France (see fig. 6), with the "Φ" shape that characterizes numerous anthropomorphic types of the same historical period; the horizontal band on the top of the legs of figure no. 1 has been interpreted as a kilt and the appendage on the left side (for the viewer) could be an accessory to the robe or an object held by the character. The small semicircle drawn immediately above the horizontal bar could be interpreted as the pelvis, or as a device to symbolically render the female sex. Also in this case a comparison with the wall paintings of Çatal Hüyük in Anatolia has been proposed (see fig. 4 and 4.1); even if executed in a less schematic style they can help to give an iconographic interpretation of this first figure in red.

"The key to understanding the other ocher images, which do not find precise comparisons in other rocky figurative complexes, must be sought within the "scene" itself. Comparing figures nos. 4, 5, 6 with the anthropomorphic n. 1 [image 7], in fact, it is evident that they are all composed of a single basic element: a closed geometric shape, tending towards the quadrangular, with an extension on the left side and a semicircle inside” (G. Biondi, 2017); this leads us to hypothesize ALL the elements of the scene as anthropomorphic, including figure 2, which seems to have, like figure 1, its legs open perhaps to represent movement. “Moreover, in post-Paleolithic rock art, in addition to the generic tendency towards abstraction, the tendency to represent the human figure devoid of one or more parts of the body is well documented” (G. Biondi, 2002). The anthropomorphic figures, interpreted as female, seem to be represented in a position of movement, perhaps dancing, perhaps praying.

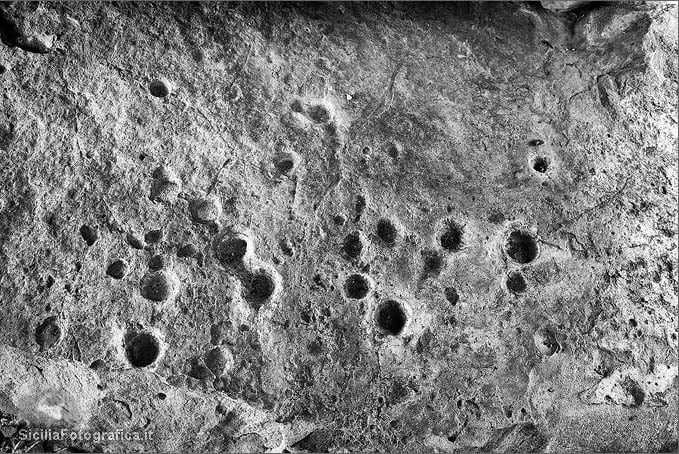

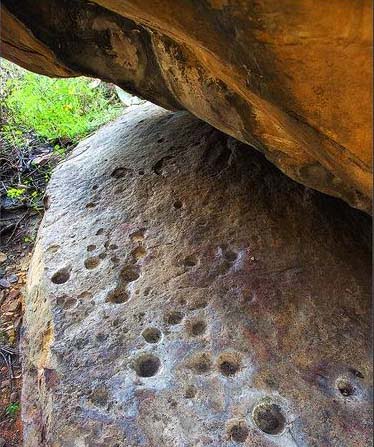

On the floor of the refuge we also find around twenty small cup marks (hemispherical conical or concave incisions, see figs. 9 and 10) of uncertain dating; among these, four are connected in pairs by a channel dug between them. The cup marks are a type of engraving that has been documented from the Middle Paleolithic up to historical times; their meaning is still controversial: perhaps designed to contain offers of liquids, perhaps astronomical representations. They are however connected to the sphere of the sacred.

Near the shelter, artifacts ranging from probable Lower Palaeolithic and Neolithic industry (obsidian blades and other stone tools) to geometric or imprinted pottery of the early or middle Neolithic have been observed; from fragments of Castelluccio material from the Early Bronze Age (including a clay horn, found a few meters from the entrance to the shelter, see fig. 11) to Greek earthenware, up to a late ancient – Byzantine phase (XNUMXth-XNUMXth century AD). These finds do not suggest a permanent human presence, but an occasional attendance.

We can hypothesize that the easily accessible site was used as a place of worship by the groups and communities of the plain of Catania and the area at the foot of Etna which, during the Neolithic, settled along the main waterways , due to the development of agricultural and livestock practices.

The location of the refuge is in fact on the western edge of the Catania plain where there were communities with livestock and agricultural practices, in an area bordering the inner and more "wild" part of the island: the site is significantly located in the plain formed by rivers Salso and Dittaino, near their confluence with the Simeto, strategic riverways used by Neolithic groups to penetrate towards central Sicily.

The data collected from the Erei area, together with those from the rest of the island and from the prehistoric caves of central-southern Italy, suggest that even in Sicily it is possible to recognize the aspects of an underground prehistoric religiosity in which the caves, and also the shelters or shelters, take on a marked ideological value: a ritual structure that includes elements such as the cult of the ancestors, the consumption of ritual meals and the cult of water; structure also highlighted by archaeological finds, but which will have to be defined with ever greater accuracy (also in its social and political aspects) in future studies.

The transformation of social relations into hierarchical structures, from the first Copper Age in the fourth millennium BC, is explicitly revealed by a growing religious and ritual activity carried out by the Sicilian communities both within the various rocky necropolises and in the caves and shelters, with a social and cultural parable that also develops in the following phases, up to the historical period.

Historical notes

The shelter takes its name from Giuseppe Cassataro, an archeology enthusiast from Acireale, who discovered it in the XNUMXs.

CARD

LATEST PUBLISHED TEXTS

VISIT THE FACTSHEETS BY OBJECT