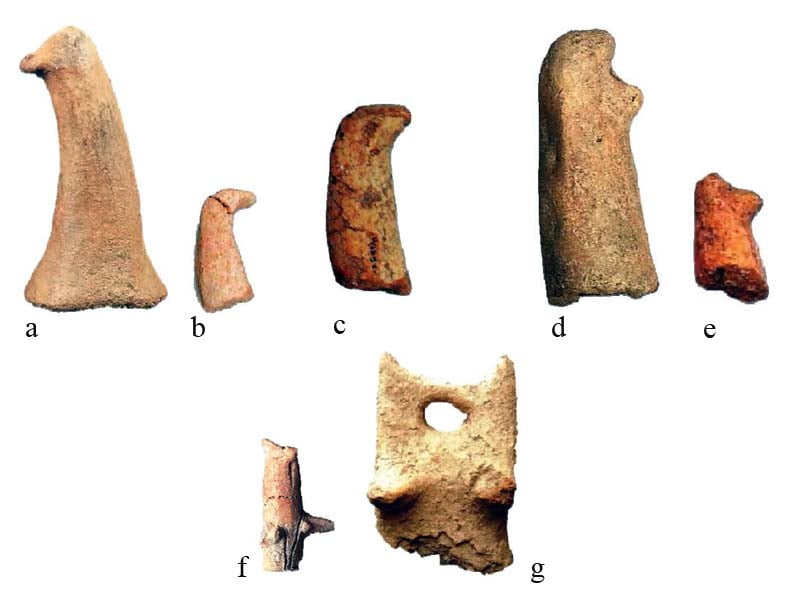

Referring to the cultural context of the megalithic complex of Monte Grande are the clay horns, or bird's beak, commonly interpreted as phallic symbols (Fig. 1a-bc) and which constitute, as highlighted by Cultraro (2010), one of the types of artefacts among those most present in Castelluccian sites, both in necropolises and in inhabited areas. Cultraro himself highlights how the places where these types of finds were found - usually a pit containing animal bone remains, as also in the case of the Monte Grande site - and the presence of other artifacts such as anthropomorphic figurines and clay models, leads us to believe that they may be objects for ritual actions or social practices. However, the high concentration of these finds also in residential contexts and their discovery near the remains of hearths leads us to hypothesize a more commonly domestic use, that is, with the function of a fire support to support pots or other cooking containers; however, this does not mean that, apart from the probable functionality of the objects, they also had a symbolic value, a hypothesis that is even more probable in the case of discovery in sites, such as that of Monte Grande or Poggio dell'Aquila di Adrano, which had a cultic and non-domestic function.

This iconography also appears in association with marked female sexual traits, as in the finding in Fig. 1f, and in this case it could represent the masculine force that causes the vital energy to burst forth and activate; in any case, as Judy Foster recalls, “the phallus symbol is significant, but not commonly associated with the goddess; when present, it is always secondary and symbolizes the female deity's partner or consort”. Among other things, it is worth remembering the attestation of this iconography already in the Stentinello I phase (5700-5500 BC) and its diffusion both in ceramic artefacts or worked in bone or ivory, more or less decorated, throughout the Neolithic, both in the figures with masks or bird's beak in the Addaura caves need Cala dei Genoese, in the case of cave paintings, a combination that prompted the scholar Sebastiano Tusa to highlight a direct link with the Mesolithic rock art tradition. These artifacts were defined as "aniconic" by the first scholars, but by now the interpretation that sees in these clay horns, including the hybrid one in figure 1f, representations of "bird's beak" or the head of a animal with an open beak (Fig. 1d-e), as references to the ornithomorphic features of the goddess. Another interesting find found in the same site is that of Fig. 1g with a flat tablet with a hole, perhaps to use the object as an amulet or votive offering, in which, in addition to the breasts, there are bull's horns. This typology was also found in other sites in Sicily and in much larger dimensions than those of the find presented here, as in the case of the trapezoidal plate mounted on a large basin on a foot, which has the shape of bovine horns and a pair of ashlars in relief in imitation of the breast, found in the town of Thapsos and also mentioned by Cultraro (2010). The scholar points out that "this element of the vase is not practical and functional, considering the imposing proportions of the basins, but must be interpreted as the abstract representation of a complex of significant connections that link the image of the woman, in her reproductive and breastfeeding power, with the animal and taurine element”. And therefore in this typology the cultic and symbolic function would be much more evident.

Dorothy Cameron, while working with James Mellart at Çatal Hüyük, has highlighted how the often widespread opinion among scholars who see in the bull and its attributes a symbol of virility and the male attribute of the Goddess, cannot fully satisfy but on the contrary, she highlighted how the bulls' heads, found numerous in sites such as that of Çatal Hüyük, can be connected more appropriately with the birth, fertility and vitality of the Feminine: we owe the intuition relating to the possible discovery to her, during the stripping process in the burials, of the extraordinary similarity between the bucranium and the female reproductive system (as well as the correspondence of the duration of 9 months of pregnancy for both species, human and bovine) which led her to interpret precisely the symbol as an attribute of the Great Mother. Maria Gimbutas will also take up this reading, confirming the profound value of the symbol of the bull, often symbolically exemplified in the form of the horns alone, as the most important sacrificial-totemic animal, "explained by its identification with the uterine organ and with the regenerative waters. From the bucranium or body of the sacrificed bull emerges new life in an epiphany of the Goddess as flower, tree, column or water substance, bee or butterfly”. Furthermore, Gimbutas highlights how the symbolic meaning attributed to the horns of a large bison was already present well before the Neolithic and Çatal Hüyük (e.g. Lady of Laussel, or Paleolithic depictions of bison heads associated with plants and seeds). The importance of this symbol is also highlighted by its diffusion in ancient Europe, in Anatolia and in the Near East, represented both in pictorial rock art and in ceramic-sculptural art: the bucrania are associated with symbols of regeneration and energy ; covered by a layer of clay they are found in the Vinca temples and, also in Sardinia, bull heads are present at the entrance to the underground tombs or next to them. To get to the underground temple, one symbolically passes through the sacred womb. There is also a symbolic link with the waters of life, sculptures of cattle from the Neolithic and Minoan and Mycenaean cultures are decorated with nets or eggs and covered by a net design, which symbolizes the water of life or the amniotic fluid .

Therefore for Gimbutas”the bull is not a god, but is essentially a symbol of becoming…a personification of the generative force of the Goddess”, often combined with energy symbols such as snake coils, concentric circles, eggs. As regards the use of the artefact, a probable hypothesis seems to be taken from the custom of decorating bovine sculptures with plants and flowers in the context of the Cucuteni culture, or the custom of Mycenaean art of making flowers sprout from the columns of life or between two bull horns, or to erect the so-called "horns of consecration", the shape of which is often reproduced by the position of some statuettes with their arms raised. In fact, the connection with the rites of seasonal regeneration could be achieved through the insertion of "perishable material such as flowers and foliage, symbolic of new life” in the hole between the horns.

CARD

LATEST PUBLISHED TEXTS

VISIT THE FACTSHEETS BY OBJECT