The Grotta del Romito, near Papasidero (CS), represents one of the most interesting and important cave sites of the Italian Paleolithic, thanks also to the excavations conducted by Paolo Graziosi in the 60s which brought to light some engraved figures of a naturalistic nature (figures of bovids) and abstract (linear signs) as well as some multiple burials, continued since the 2000s with new excavation campaigns and discoveries.

The Romito site is located in the Pollino National Park, 275 meters above sea level at the foot of Mount Ciagola and near the Lao river - already active during the Paleolithic era and used as a communication route, for food and lithic resources - and constitutes one of the most important deposits in southern Italy. Its relevance in the context of prehistoric sites is linked to the impressive stratigraphy which, as Prof. Fabio Martini explains, covers a time span from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic, revealing important finds for the historical reconstruction of the activities of the human communities that inhabited the site, their living conditions and interactions with the surrounding environment and landscape, as well as information on the fauna and on the conditions suffered by the communities from the climate changes that occurred between the end of the Paleolithic and the Neolithic. In fact, traces of the presence in the cave of a stream have been identified, prior to 24.000 years ago, which had alternating phases of swelling over the centuries and, following drying up and reclamation interventions, allowed human attendance of the site for a very long time. In the lower levels of the cave it is thought that human occupation was sporadic, due to a greater presence of the waters of the small stream inside the cave itself: the data derived from sediment analyzes and chronostratigraphies highlight the beginning of a cold-humid climate. Subsequently, a cooling of the climate occurred, confirmed by the faunal remains found belonging to both wooded and mountainous environments (ungulates, such as wild boar, ibex, chamois, deer) and plains and open spaces (horse, aurochs). Human groups therefore had the possibility of frequenting different habitats, even far from the site, for their hunting activities, and in general the area remained favorable to the life of human communities, with an abundance of resources until the Neolithic. Precisely relating to this era are the obsidian finds that would identify this geographical area as an exchange and transit area, between the Tyrrhenian and Ionian sides, of volcanic glass coming from the Aeolian islands, thus confirming the importance of the Neolithic populations of Calabria in the trade and control of this resource. From the analysis of the remains of fauna and microfauna and vegetation it emerged that the area was particularly favorable to human settlements: presence of water, woods and meadows and above all a gradual transition to increasingly favorable climatic conditions (humid and temperate).

The site is made up of two parts: the actual cave which is approximately 20 meters long, and the shelter whose extension is approximately 34 metres, and also includes parts that have not been completely explored. In the Paleolithic era the cave and the shelter formed a single, very large living space, but in more recent times an artificial enclosure with a wall was built to use the cave as a hermitage (hence the current name); part of the wall was then further incorporated into the rock due to karst phenomena and limestone formations, so the internal spaces are now completely separated from the external shelter and only a narrow passage remains which constitutes the actual entrance to the cave.

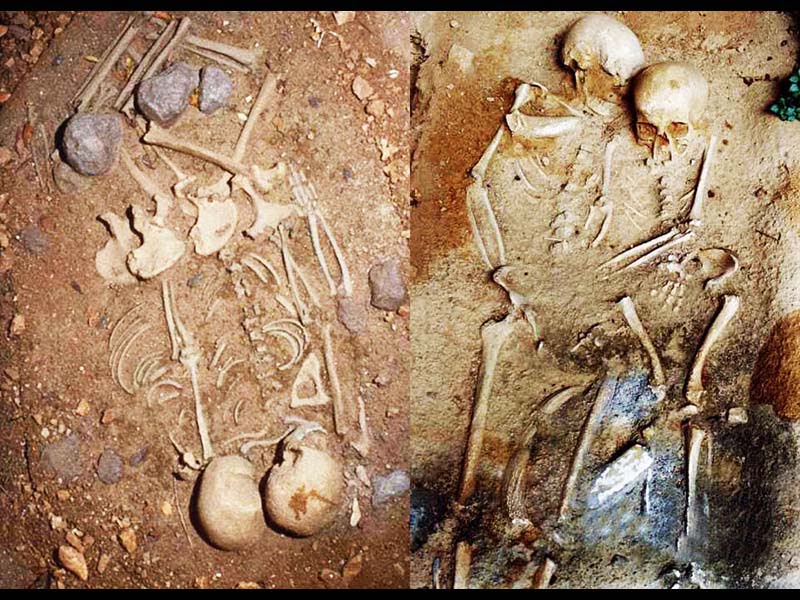

During the excavations, carried out from 1963 to 1967, conducted by the Superintendency for the Archaeological Heritage of Calabria and by the Italian Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory with the direction of Prof. Paolo Graziosi and the collaboration of Dr. Mara Guerri and Prof. Santo Tinè, burials and numerous lithic and bone finds came to light. Of great anthropological interest are the two rocky masses found at opposite ends of the shelter:

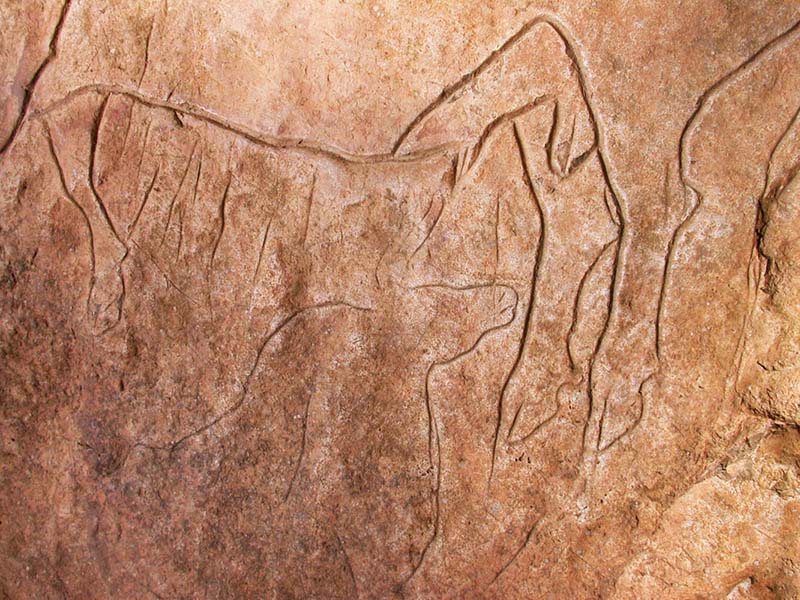

- the first, on the eastern side of the shelter, approximately 3,50 meters in size, is covered with numerous linear incisions (Fig.2), segments engraved more or less deeply, with different patterns (straight, curved), arranged in multiple directions without any organization in the composition and without any apparent meaning, whether in groups or scattered, and represent a recurring motif in European rock art, especially of the final Upper Paleolithic. There are also several testimonies of them in other Italian sites (Sicily, Puglia, Liguria) both as free-standing engravings and as signs that cover zoomorphic engravings.

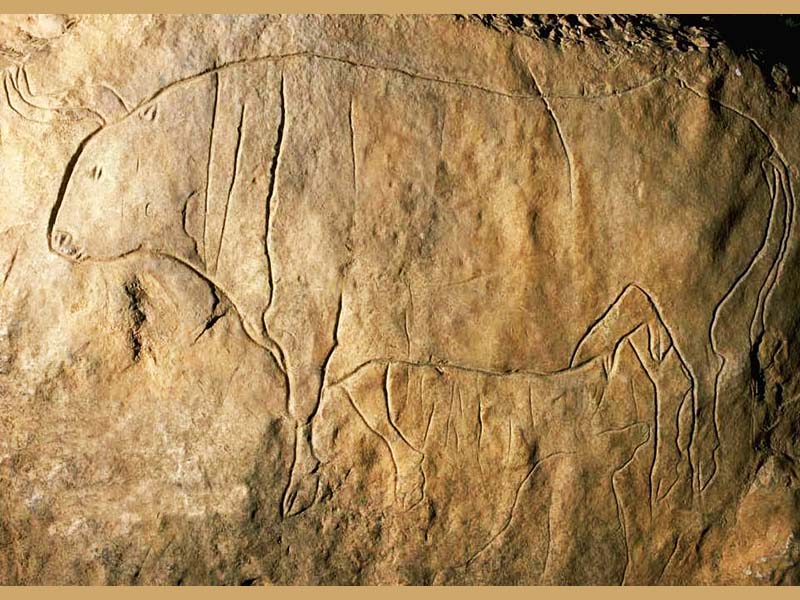

- On the second boulder, called "of the bulls", almost two and a half meters wide, located on the limit between the internal area of the cave and the external one of the shelter, the linear signs mentioned above were used to engrave a large aurochs (Bos primigenius), a wild bovine ancestor of domestic cattle (Fig.3), 120 cm long and with perfect proportions. In addition to the horns, both seen from the side, projected forward and with a closed profile, the nostrils, the mouth, the eye and the folds of the neck have been reproduced in detail.

Prof. Paolo Graziosi studied the site during the first excavation campaign, placing the rock engravings in the Mediterranean stylistic context, in which the reproduction of geometric and abstract themes is evident, and found in Franco-Cantabrian Paleolithic art and stated that "one gets the impression that at least part of these signs pre-existed the execution of the bull and that some were even used to create the large folds”. Analyzing in particular the figure of the largest bovid, so perfect in design and perspective, and also in the choice of the rock surface which guarantees three-dimensionality, he stated that he was faced with "the most majestic and happiest expression of Mediterranean Paleolithic realism, due to a Michelangelo of the time”. Between the hind legs of the aurochs there is engraved, much more subtly, almost sketchily, another image of a bovine of which only the head, the chest and a part of the back are executed (Fig.4). This too is represented with the horns projected forward, divided in two only in the second half, whereas in the first part there is only one horn, repeating a typical module of Mediterranean Paleolithic art. Finally, a third small bull's head is engraved on the lower part of the same boulder. Next to the boulder with the bull there is a stalagmite in the shape of a headless equid. Graziosi also argued that “the discovery of the burials in the area around and between the two large engraved boulders would suggest two steles or one stele (the one with the bull) delimiting a funerary area”; in fact the occurrence of aurochs remains together with skeletons refers to functions of funerary offerings, elements that provide information on the symbolic universe, Paleolithic ritual and funerary practices. Prof. Fabio Martini, who succeeded Graziosi in the subsequent and more recent excavation campaigns, assigns to this image a highly suggestive totemic value and gives the entire environment an indisputable link with the sacred. In fact, considering the position of the boulder at the entrance to the cave, it seems that the image of the bull was placed as a totem of the community, recalling its importance in propitiatory rites for hunting. It is also important to note that the style of the Grotta del Romito recalls that of the Levanzo, Addaura, Niscemi and Puntali caves. In addition to the environmental data that give the possibility of reconstructing the fauna, flora and landscape of the Paleolithic, the site of the Grotta del Romito is also very important for the finds relating to objects of daily life, artistic production and funerary rites and to burials.

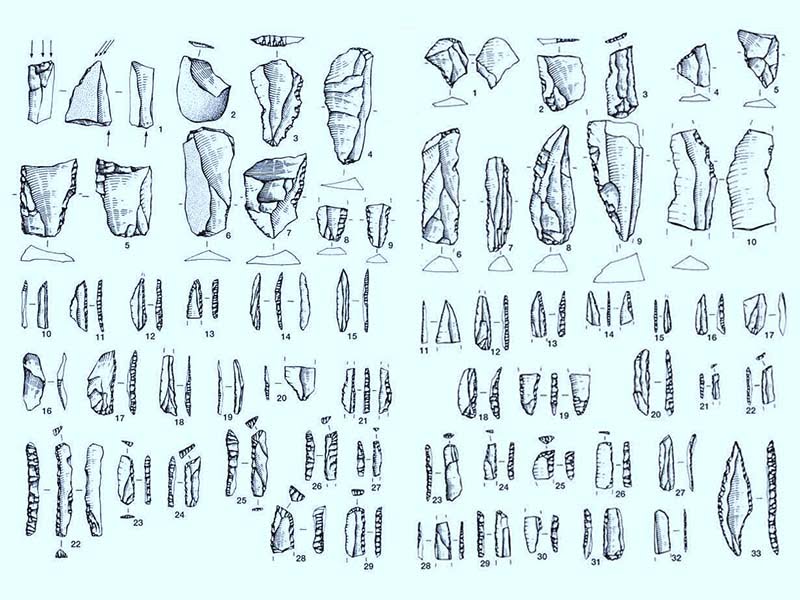

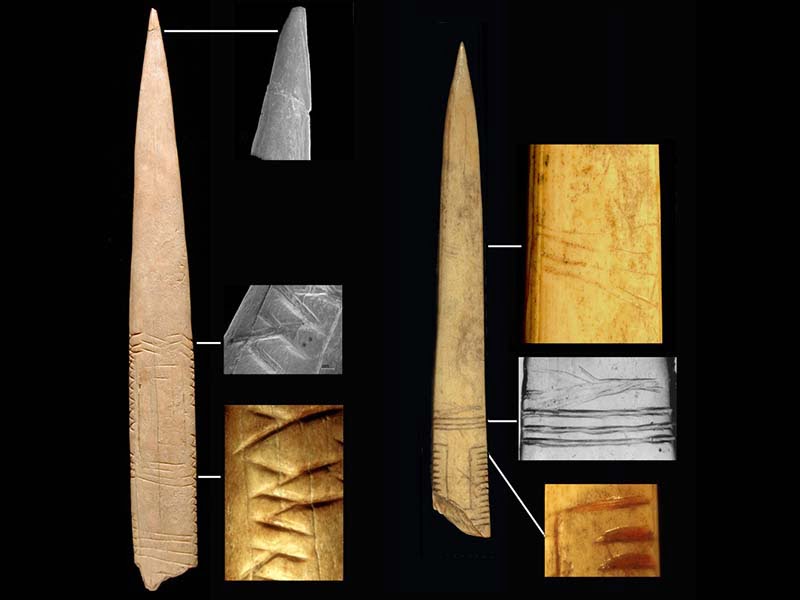

Regarding the objects (lithic and bone industry), we note the discovery, already from the first excavations of the 60s, of numerous so-called deep-backed points (Fig.6), certainly functional to hunting activities, and of two zagaglie made of bone, artefacts with a sharp point, also in this case intended for hunting, with geometric decorations (Fig. 6). These were found by Graziosi already in the first excavations and represent important evidence of the so-called Paleolithic furniture art; they were obtained from the diaphysis of the aurochs metatarsal and therefore, given the correspondence with the rock engravings, one is led to think that the bovid represented a great meaning, probably totemic. Both are fragmentary at the base and have slightly different dimensions, around 13 cm, and have an ogival shape. In the first, the geometric motif is formed by a rectangular figure that frames another, both surrounded by parallel, straight and zigzag lines and wolf's tooth marks at the edges of the object. In the second the decoration is made up of small parallel horizontal notches on the edges and other longer lines, always horizontal and grouped, whose compositional decoration scheme finds analogies with other European examples. Due to the fragmentation of the objects it is not possible to grasp the complete decoration, even if the tip part remains undecorated. The analyzes with the scanning electron microscope have shown that the engraved lines, made with a stone tool, present a good regularity, the tip was made by scraping again with a stone tool followed by rubbing with a soft material, perhaps skin. The most interesting fact is that there are no traces of wear on the objects, demonstrating that they were never used for hunting, and therefore it is likely to hypothesize that they were symbolic and/or cult objects, connected to funerary rites; hypothesis supported by the presence of traces of red ocher in the linear engravings of zagaglia n.2. We also remember that the lines that rise and fall, the zig-zags, symbolically recall the ripples of the water on the surface and therefore can be a symbol of movement, reconnecting to the energy of ascent and descent, of calm and strength, life force , rebirth.

Historical notes

The cave was discovered on the property of Mr. Agostino Cersosimo in 1961, by the director of the Municipal Museum of Castrovillari, following a report from two people from Papasidero, Gianni Grisolia and Rocco Oliva, during an agricultural census; it is located 14 km from the urban center of Papasidero in a valley to the left of the Lao river. In fact, already in 1954, an archeology enthusiast from the town of Laino Borgo had reported the shelter by highlighting the presence of the figure of a bull in what was the entrance to the cave. The studies were then entrusted to Paolo Graziosi, who directed the work until 1968. Since the 2000s, the care of the site has been entrusted to one of his disciples, Prof. Fabio Martini, who succeeded him in leading the Department of Palethnology of the University of Florence. The research continued through an interdisciplinary perspective involving paleethnologists, anthropologists, naturalists, also with the intention of obtaining new data from the old stratigraphic series, and expanding the area of research also in areas of the cave not previously analyzed. In fact, starting from 2011, the stratigraphic excavations also extended to the area of the external shelter, which confirmed a Mesolithic occupation dated to a period between 10.500 and 9.000 years from the present and which therefore documents a continuity in the presence of human communities in the area.

The Grotta del Romito is located 296 meters above sea level at the foot of Mount Ciavola in the locality of Nuppolara in the municipality of Papasidero, in the Lao river valley, in the province of Cosenza, and is therefore part of a naturalistic environment of great charm: they are typical geological characteristics of this landscape the karst caves, shelters and gorges. The name depends on the attendance of the monks of the monastery of Sant'Elia who used it as a hermitage since the year XNUMX. The site is currently accessible thanks to the collaboration between the University of Florence and the Florentine Museum and Institute of Prehistory with the Archaeological Superintendency of Calabria and the municipality of Papasidero. In fact, interventions have been carried out on the site that guarantee access to the cave, such as walkways, adequate lighting systems and the integrated use of the archaeological site, also providing guided tours and activities and educational aids for children. Furthermore, in the antiquarium located on site it is possible to see some exhibits on display.

CARD

LATEST PUBLISHED TEXTS

VISIT THE FACTSHEETS BY OBJECT