di Barbara Crescimanno

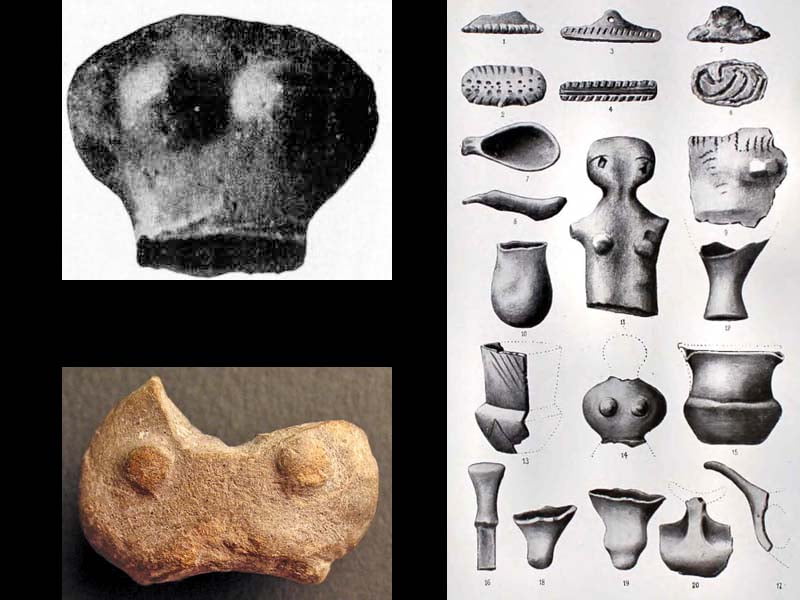

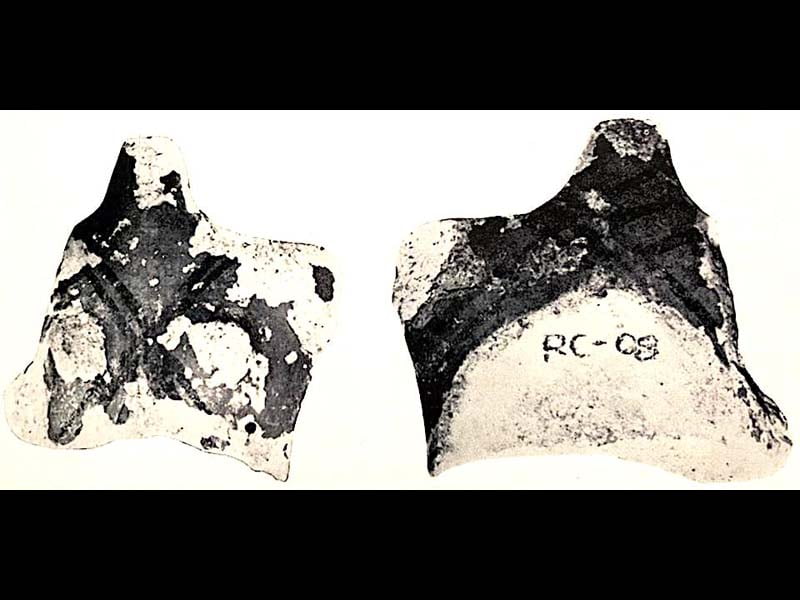

At the Salinas Archaeological Museum in Palermo are preserved two "lozenge" idols in dark clay, about 10 cm high, dating back to the Middle Eneolithic (mid-XNUMXrd millennium BC) and found in a tomb found in front of the gate of the Regia Favorita Park , in Piazza Leoni, in the plain surrounding Monte Pellegrino. The two finds, described in the "Lozenge-shaped idols of Palermo”, are compared by Angelo Mosso with “similar figures from the Aegean. The ground is speckled in black to give it the characteristic brindle appearance we found in the dress of the priestesses on the painted sarcophagus of Haghia Triada. This coincidence is instructive in explaining the relations of the Minoan cult with Sicily".

Mosso compares the Palermitan idols with other so-called "flat" idols: the first two, from Haghia Triada (Festos, Greece), have stumped arms as in the Palermitan specimens but with the breasts in evidence, unlike these; the other find in comparison, fragmentary, instead comes from cave of the Arene Candide in Liguria.

These are the very first comparisons, dating back to the beginning of the last century, between idols of different geographical origins: we are now proposing others, starting from Sicily itself.

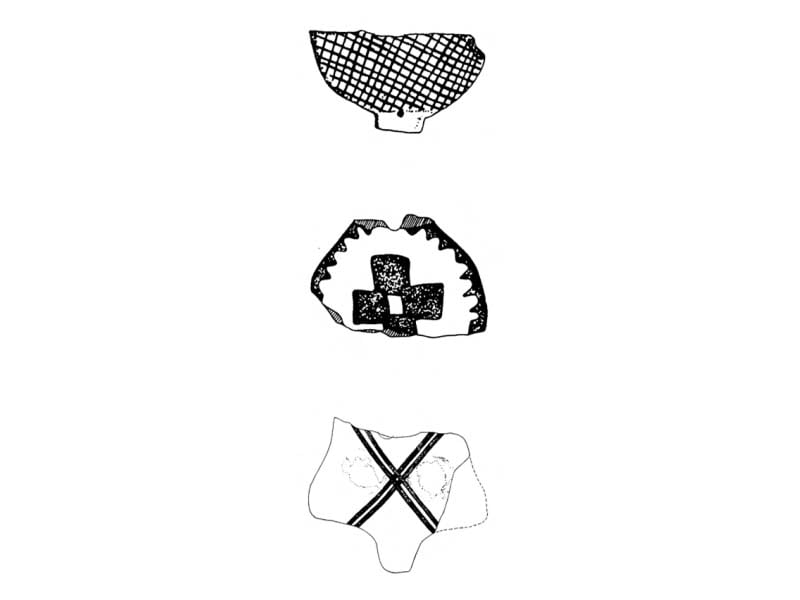

A female idol was found in the village of faces castellucciana della Torricella, near Ramacca (Catania), together with numerous other pottery fragments, in a deposit probably leached from the oven tombs of the necropolis above. While the rest of the pottery found seems to approach the Etna types, the idol, although mutilated, has notable affinities with those of Palermo. It is a female figure with breasts in relief, entirely covered by a glossy red varnish on which a decoration of black lines stands out: two of these, parallel, cross each other in diagonal bands on the chest and three, similarly, on the back, creating a design similar to the cross-shaped decoration of the Palermitan idol (also present on both the front and back sides of the find). Traces of at least one horizontal line remain on the neck. Numerous clay fragments of other types of objects found together with the statuette (such as seals, containers, oil lamps, spindle whorls, etc.) have the same type of decoration with crossed bands.

This X decoration, executed with parallel lines in the case of Ramacca and with filled bands in the case of the Favorita, is one of the elements that strongly unites - from a symbolic and stylistic point of view - the two finds. “It is an element of the widest diffusion both in time and in space, whose constant repetition [...] appears with a certain frequency since the fourth millennium on numerous terracotta, stone and bronze figurines from Mesopotamia to Central Europe”; in all cases they are more or less schematized female figures, whose gender is highlighted by the representation of the breasts or the vulva (GM Sluga, 1973).

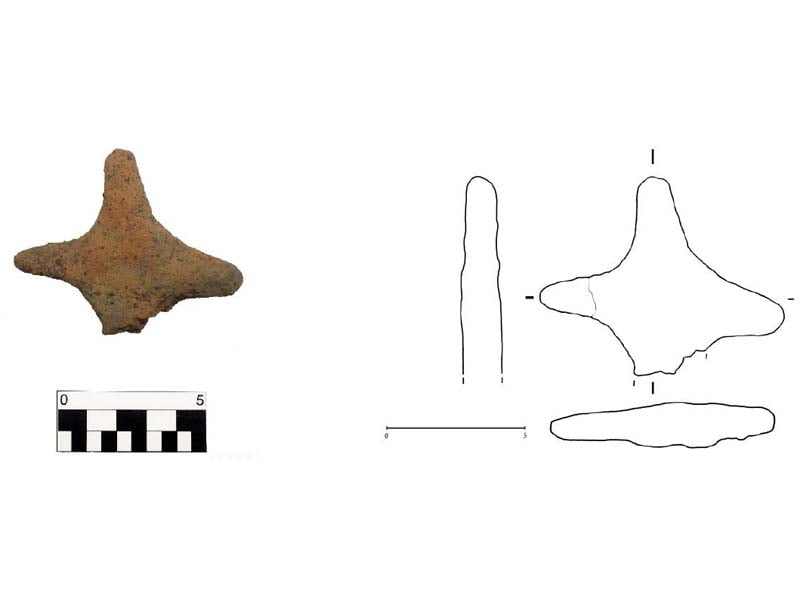

A second comparison is possible with a fragment of a figurine recently found in Valcorrente near Belpasso (Catania), on the south-eastern slopes of Etna, a site occupied since the end of the Neolithic where, in the Early Bronze Age, structures were built circular plan; on the floor level inside one of these enclosures ceramics of the Rodì-Tindari-Vallelunga style (RTV, Bronze Age), spindle whorls and fragments of clay horns/phalluses were found which characterize the space as an area of production and symbolic-ritual activity.

The figurine we are interested in, extremely coarse and unfortunately fragmentary, is made up of an orange colored impasto with black inclusions (probably volcanic), the head elongated in a conical shape, stumps of arms in a horizontal position and two small, slightly protruding breasts; the lower torso is broken; therefore, we do not know if it ended up with a flat base to place it vertically, as in the other specimens.

The analysis of this type of anthropomorphic figurine, in the manufacture of which there seems to be no descriptive but rather symbolic interest, appears particularly complex; moreover, the documentation that has come down to us, except in exceptional cases, is strictly limited to objects made with non-perishable materials: a very small part of these productions. However, Guarnera goes so far as to state: “That these figurines can be linked to rites of passage, for example from the condition of a young person to the status of an adult, is well known in the Aegean and Mediterranean world”. The contextual discovery of spindle whorls, clay horns/phalluses and fire pottery leads her to associate the figurine with a cult linked to the female sphere, and to hypothesize a female production of such artefacts which "could perform the most disparate functions: from dolls to 'pedagogical' representations used during initiation ceremonies, from votive in defense of the dead".

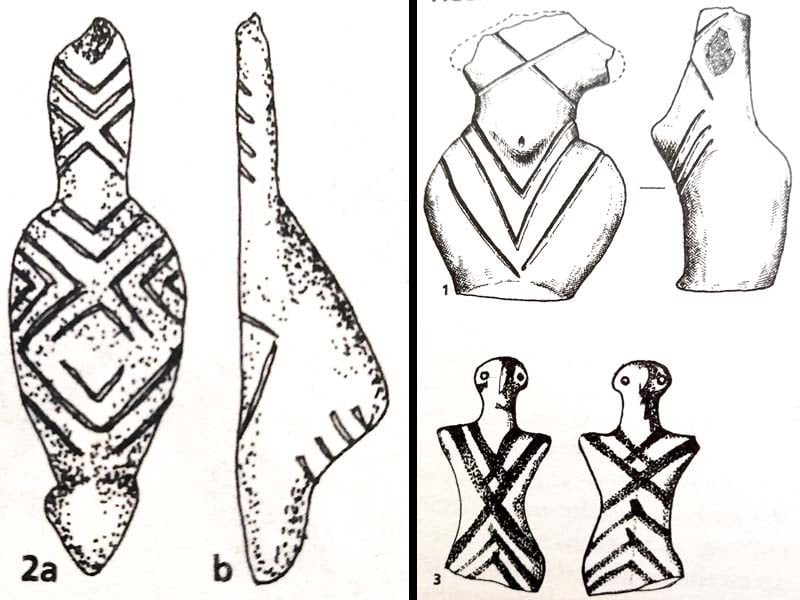

According to the researcher, some interesting morphological parallels can also be found with some statuettes from peninsular Italy: one dating back to the recent Bronze Age from Montebello Vicentino, and one datable to the Final Bronze Age from Frattesina, both cruciform in shape, stylized and asexual.

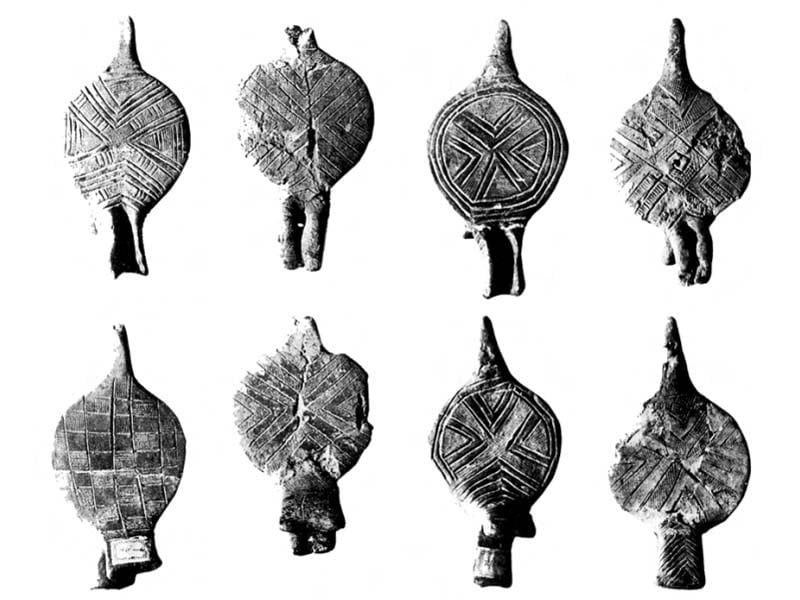

Giannitrapani, in one of his articles, reports other interesting elements for our comparison: the scholar compares some so-called "disk" idols, a typology attested by some fragmentary specimens from Manfria (L. Bernabò Brea 1976-77, pp. 57-58 and 73) and Barriera di Catania, and uses them to discuss contacts between Sicily and Malta in the early Bronze Age.

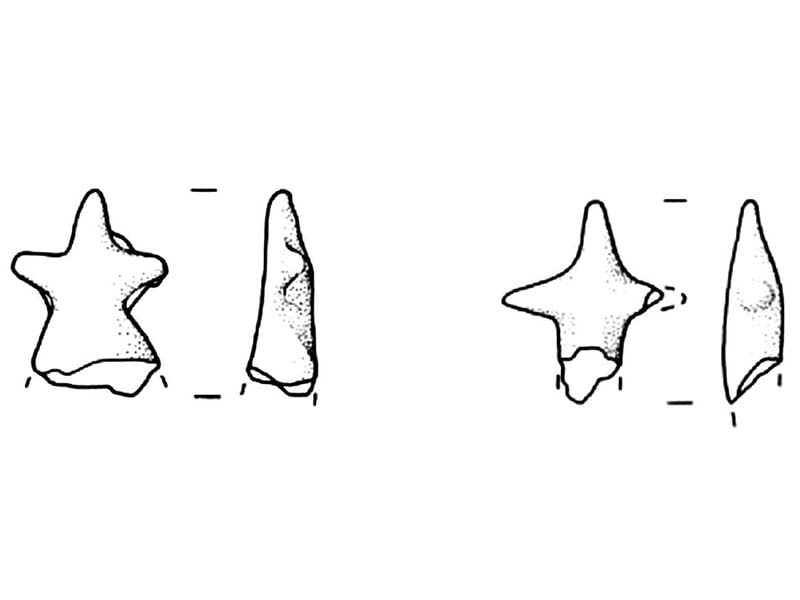

The surfaces of some of the statuettes reported by Procelli are in fact painted with the same motifs of crossed bands that we encountered in the Palermitan example and in that of Ramacca; these statuettes are interpreted as a “Sicilian variant of a type very common in Malta in faces of Tarxien Cemetery, where the decoration, instead of being painted, is engraved, taking up the techniques in use for the production of vases. The discoid part of these little idols has been interpreted [from Bernabò Brea] such as the stylization of rigid priestly hoods particularly ornate and completely covering the chest” (E. Giannitrapani, 1997).

Marija Gimbutas interprets this series of figurines from the Tarxien necropolis as ornithomorphic reproductions with human legs and tails, and the decorations we have called “X-cross bands” such as chevrons and Vs.”Graphically the most direct way of rendering the pubic triangle is to draw a V. This expression and its recognition are universal and immediate, but it is nevertheless surprising how soon this 'shorthand' trait crystallized to become, through countless ages, the hallmark badge of the Bird Goddess. [...] Some representations of waterfowl are clearly anthropomorphized".

According to the scholar, the association between these symbols (V, chevron or V interconnected or juxtaposed in X-shaped crossed bands formed by two Vs whose vertices touch) and the images of the ornithomorphic Goddess or Bird Goddess remains constant for millennia, from the Paleolithic up to the Bronze Age, and we have several iconographic examples, of which we report a brief rundown.

All examples show stumps of arms instead of wings and, in the Moldavian example, a rostrate (beaked) face.

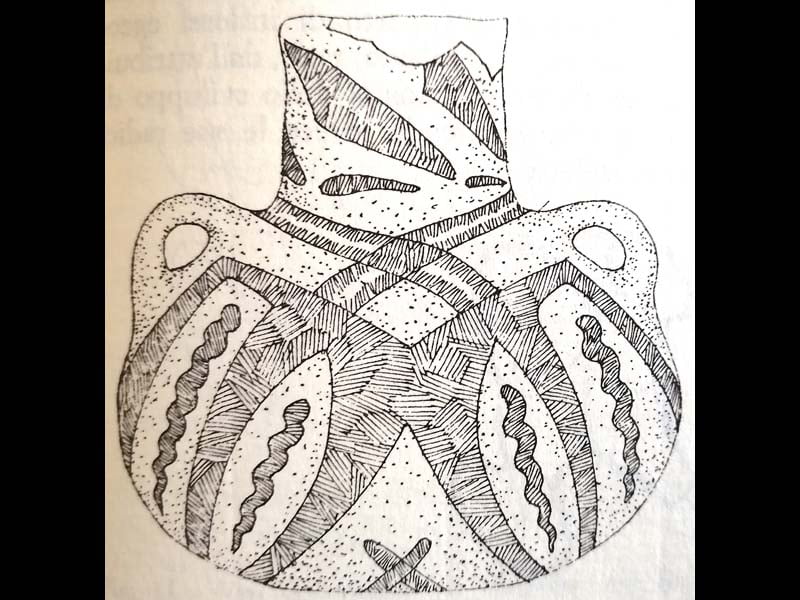

The Paleo-Elamite example seems to create an "iconographic bridge" between the different historical periods and geographical areas that we are comparing, confirming the hypothesis of Bernabò Brea, for these signs and engravings, of a stylization of specific symbolic elements necessary for the representation of ornate priestly robes; the statuette from Turkmenistan instead highlights and confirms the ornithomorphic symbolism of this iconographic typology. The V or X signs, multiplication of the vulvar symbology that characterizes the anthropo/ornitomorphic statuettes, are also found on other types of objects, as we have seen for the Ramacca finds; We also find a similar juxtaposition in Palermo: a painted vase of the horizon of Serraferlicchio (Copper Age), with similar symbology, was found in the Colli-Favorita district, not far from the place where the two Palermitan idols were found.

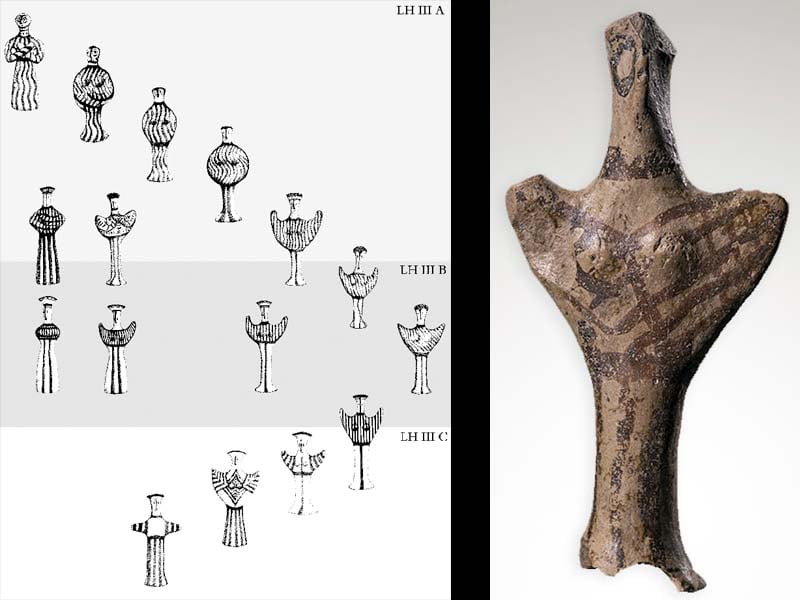

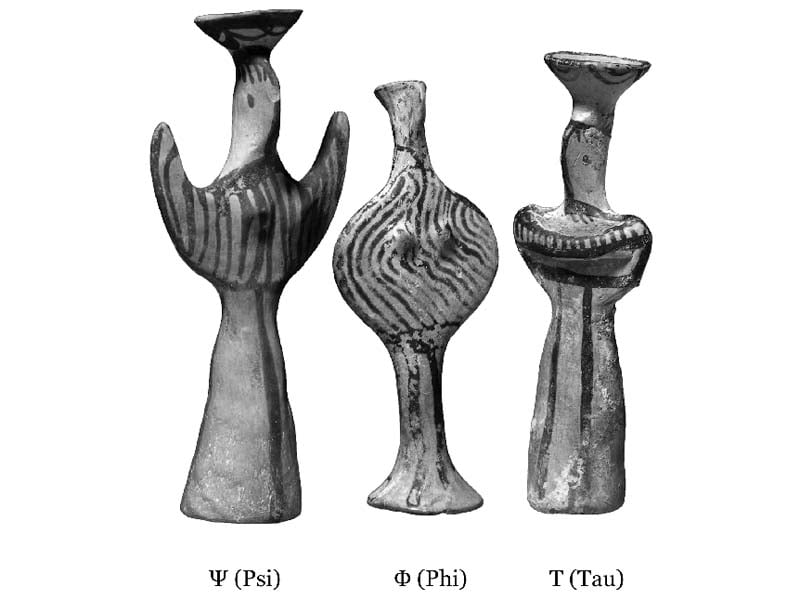

At this point we open a comparison with a wider range: to the examples from Sicily, from Malta, from various parts of Ancient Europe, we add the very numerous series of statuettes found in the Aegean-Cycladic area. In the images we report a diagram illustrating the stylistic development, during the Late Helladic ('LH', 1550-1000 BC), of this type of statuette, all female. Mycenaean idols have also been found in Italy, for example in Puglia: the Mycenaean emporiums on the Taranto coast are widely documented, as evidenced by the idol 'a psi' (ψ) found at Scoglio del Tonno and dating back to 1375-1350 BC

The three main types of Mycenaean terracotta figurines take their names from three letters of the Greek alphabet. The Sicilian statuettes of Salinas have elements coinciding both with the Mycenaean type called 'a phi' (φ) which also belongs to the first idol from Haghia Triada mentioned by Mosso, and with the last, late example of the “Psi” type.

In comparing the Helladic, Maltese and Sicilian productions it is necessary to point out that, as far as it is possible to establish morphological and iconographic comparisons, they can never be perfectly punctual: this is because "local productions, variously influenced, incorporate and rework iconographic models of wide circulation and sharing, with results that differ from site to site” (VR Guarnera, 2020).

An example of this circulation and variability, the last one we present, still comes from Sicily, in particular from the Aeolian Islands, which are also included in the Mycenaean exchange circuits.

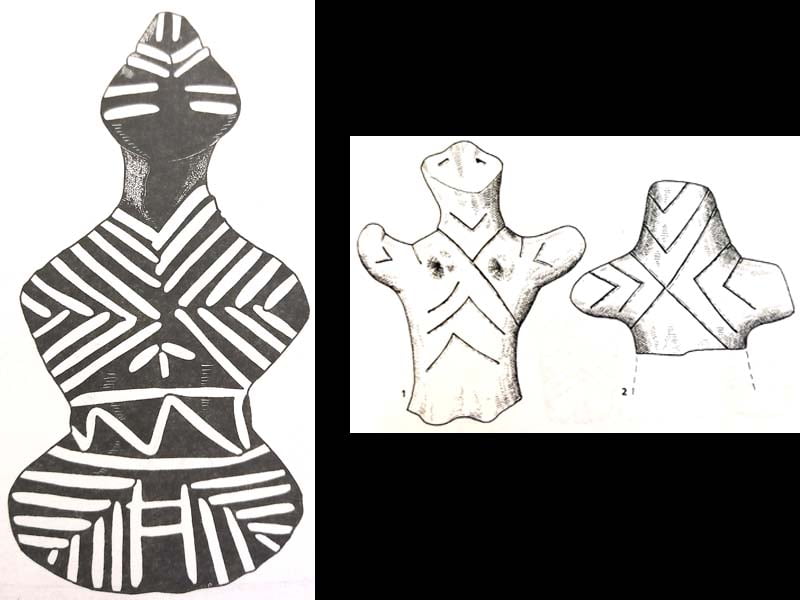

Inside the "gamma III" hut on the Rock of Lipari (Aeolian Islands), a site inhabited since the Neolithic period, two female idols were found, again dating back to the Bronze Age (faces Thapsos-Milazzese), similar in typology but different in style. The first, missing the head, has decorations of the robe rendered with red-brown wavy vertical bands, and a horizontal band that seems to indicate a wide belt; the idol is identified by French and Mastelloni as one kourotrophos of “proto-phi” type (Late Helladic III A, XNUMXth century BC).

Kourotrophos ("nurse of infants") is an epithet of divinity who has among the characteristic skills that of feeding, educating, protecting young people. Examples are Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Eileithyia and the Nymphs, figures who oversee the rites of passage and pose as educators and protectors of childhood. The deities kourotrophoi they are usually represented with an infant in their arms or with their arms gathered around the bust or under the breast, in the synthesized gesture of a hug. Their role is to help in birth (like Eileithyia, pre-Hellenic goddess protector of childbirth) or in the transition from childhood to adulthood (like Artemis and the Nymphs). The type of kourotrophos, well present in Sicily, it is less reproduced in Egypt and in the Minoan, Cypriot and Mycenaean areas. According to Lynn Budin, this rarity arises from the transformations of gender relationships and from the progressive affirmation of a society centered on succession through the paternal line.

The second idol is even more interesting for us: it seems to represent a local imitation of the Mycenaean type "a Psi", and is extremely similar to the other Sicilian examples: the head is schematically triangular, with a pronounced nose (or perhaps with a beaked face); the arms are stylized stumps; two protuberances signal the breast; the entire surface of the body is decorated with irregularly scattered impression holes; the underside is sadly missing.

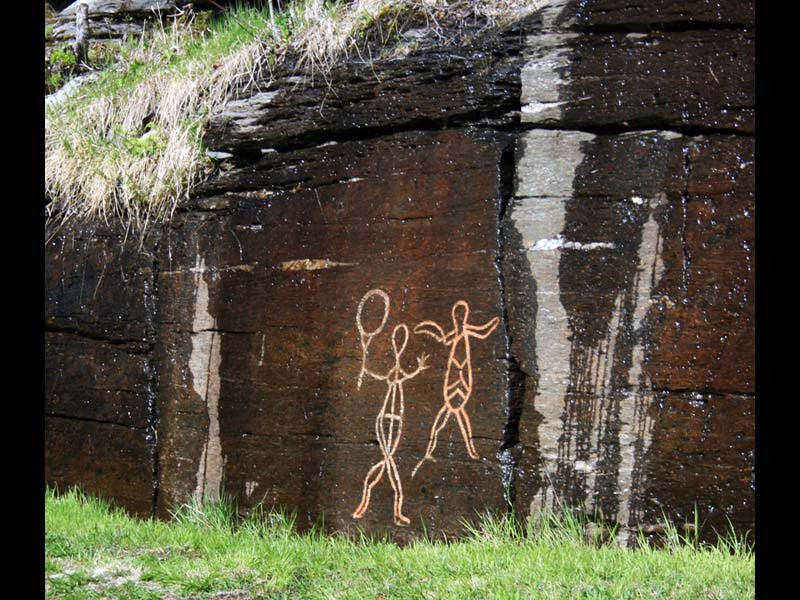

This ornithomorphic iconography, with outstretched arms resembling wings and a face with a beak nose, would instead seem to represent the opposite ritual passage to birth: that of death, physical or initiatory, over which the bird Goddess presides. An approach in this direction – highly risky due to geographical distance, but suggestive – is suggested by the rock engraving representing a shaman with a drum, from Kvaløya in Norway. Among some Mesolithic petroglyphs dating back to 4700 BC, two human figures (about 70 cm tall) have recently been interpreted as two women in a dance pose, one of whom is holding a drum; or as a shaman in trance with her spirit next to her body soaring into the air; the second figure is in fact engraved higher up than the first, with arms that seem to have the shape of wings: birds are a common metaphor of shamanic flight and the shamans, among their various tasks, had that of accompanying death (physical or initiatory).

Different cultures evidently met and perhaps coexisted in this Liparot hut.

Maria Amalia Mastelloni recalls how "the rounded huts of the villages [let them be] rich in materials both locally produced and imported from the Aegean, Mycenaean, Sicilian, Italian and Sardinian worlds. [...] These settlements change and from the Early and Middle Bronze Age (Capo Graziano and Milazzese culture) are characterized by Mycenaean frequentations, documented not only by imported Mycenaean ceramics and "Italomycenean" ceramics, but also by local imitations and other expressions to acquaintances and acquired ways”.

Recent research reveals a shared Mediterranean genetic continuity, a very ancient genetic flow which in the Neolithic era, with a subsequent important contribution during the Bronze Age, spread from Cyprus and the Anatolian islands to Calabria and Sicily, passing through Crete and for the Aegean islands. This common genetic substratum would be the result of several waves of migration, which began long before the Greek expansion that led to the birth of Magna Graecia[1].

The Mediterranean Sea has played a fundamental role in human migration processes from the Levant and the Near East to Europe during the main phases and cultural changes linked to the population of the continent.

Sicily and Southern Italy appear to belong to a broad and homogeneous genetic domain, shared by large portions of the current south-eastern Euro-Mediterranean area referred to as the "Mediterranean genetic continuum".

The iconographic comparisons proposed here, therefore, tell us about commercial and cultural exchanges that accompany traveling populations; similar statuettes but with notable stylistic differences, coming from extremely varied types of sites (religious buildings, tombs, homes), can suggest very different uses or a transversality of cult spaces that do not distinguish the sphere of the sacred and the profane as we are led to today Do. Are these images of priestesses or offerers? Ex-voto? Cult symbols? Objects for domestic rituals concerning birth and death? We can hypothesize that the people who have used these objects have taken care of accompanying the members of their community in the different ritual phases of the passage of life such as birth and death, but we don't have the certainty. Certainly we have the testimony that, beyond - perhaps superficial - stylistic and geographical differences, there was a sort of Koine culture between the various shores of the Mediterranean.

Barbara Crescemanno, February 2023

[1] The research, published in "Nature Scientific Reports” was carried out by researchers from the University of Bologna, in collaboration with the Max-Planck-Institut for the science of human history in Jena, the National Geographic Society and the University of Tirana. Ancient and recent mixture layers in Sicily and Southern Italy trace multiple migration routes along the Mediterranean

REFERENCES

- Arthur Issel – “Prehistoric Liguria” – in Proceedings of the Ligurian Society of Homeland History – volume XL – Genoa 1908;

- Luigi Bernabò Brea – The excavations in the Arene Candide cave – Part I – Institute of Ligurian Studies, Bordighera 1946;

- Luigi Bernabò Brea – Aeolian Sicily and Malta in the Bronze Age - 1976-77;

- Jole Bovio Marconi – Pyramids and other fictile objects from the Palermo Museum – Bulletin of Italian Paleoethnology II – Rome 1938;

- Stephanie Lynn Budin– Images of Woman and Child from the Bronze Age: Reconsidering Fertility, Maternity, and Gender in the Ancient World – Cambridge University Press 2014;

- Antoine De Gregorio – The iconography of the prehistoric collections of Sicily – Brancato Publisher 2003;

- Elizabeth French – “The Development of Mycenaean Terracotta Figurines” – in The Annual of the British School at Athens – vol. 66 (1971) - p. 101-187;

- Enrico Giannitrapani – “Relations between Sicily and Malta during the Bronze Age” – in First Sicily, at the origins of Sicilian civilization – Ediprint 1997;

- Marija Gimbutas – The language of the Goddess – Venice 2008;

- Valeria Rita Guarnera – “A fragment of an anthropomorphic figurine from the site of Valcorrente (Belpasso): typological study and interpretative proposal” – in Prehistory hypothesis - 13/2020;

- Maria Amalia Mastelloni – “Drawing the lines, dividing the territory: the divided space and the foundation of some western apoikiai” – in Thiasos Journal of archeology and ancient architecture 5.2 – Conferences – 2016 – pp. 7-32;

- Giuliana Messina Sluga – On a Castelluccian idol from Ramacca (Catania) – Archaeological Sicily 21-22 – 1973;

- Angelo Mosso – Origins of the Mediterranean civilization – Treves Brothers Publishers – 1912 – pp. 92-93 and 127-130;

- Enrico Procelli – “Religious aspects and transmarine contributions in the culture of Castelluccio" - In Journal of Mediterranean Studies –1991;

- Sebastian Tusa – Sicily in prehistoric times – Sellerio publisher – 1999;

- Andrea Vianello – “Problems of Identity for Mycenaean Figurines" - In Anthropomorphic and Zoomorphic Miniature Figures in Eurasia, Africa and Meso-America Morphology, Materiality, Technology, Function and Context - edited by Dragos Gheorghiu and Ann Cyphers – Archeopress – 2010.