di Giusi Di Crescenzo

It all started with the passion that the doctor of Corropoli, Concezio Rosa, put into looking for, in the area where he lived and worked, some more information on what the farmers of the area were finding while they were hoeing the fields: mostly worked stones called "lightning bolts" because they were considered lightning that fell from the sky and then resurfaced on the surface, which were kept as good luck charms and often hung around the necks of children.

Numerous arrows were then found in almost every farmhouse in the Vibrata valley; but as those who had collected them ascribed to them miraculous virtues, and several had inherited them and kept them as a life and property insurance policy, the owners could hardly be persuaded to give them up for the sake of science.

The belief that flint arrows are produced by lightning and from it preserve the houses that welcome them can be said to be common in the countryside and in small towns. Dr. Nicolucci narrates that “… in the towns of Abruzzo Ulteriore II which surround Lake Fucino, in the Marsica, the cusps of arrows and spears are called tongues of Saint Paul; and as he encounters some villager to find some, kneeling down he bends devoutly to the ground and with his own tongue he collects them and keeps them as a very powerful amulet. In the Vibrata valley the villagers indicate these weapons with the name of filth and they are sure that by possessing the celestial filth, their hut, the family and the oxen, together with seven other houses or huts around, are insured against divine punishment …” (John Capellini – The Stone Age in the Vibrata Valley - 1871).

The village of Ripoli is a significant prehistoric settlement, built on a river terrace to the left of the Vibrata river near Corropoli in the province of Teramo. Concezio Rosa made his first discoveries around 1865 and the first explorations around 1873. He defined the find as a station-workshop thinking that only in a manufacturing workshop could one find such an abundance of lithic finds (blades, arrowheads and scratchers). Everything else had seemed to him nothing more than "meal and kitchen remains" as we read in his essay "Studies of prehistory and history".

Opposed by institutions and intellectuals, however, he was also supported by scholars such as Giovanni Capellini, founder of a research institute called the Congress of International Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology. With his work he managed to collect 5163 objects – which after his death ended up in the Pigorini Prehistoric Museum in Rome – and to start a period of excavations which significantly contributed to the knowledge of the Neolithic as "the era of villages" and to indicate Ripoli as a unicum in the panorama of Italian archaeological sites.

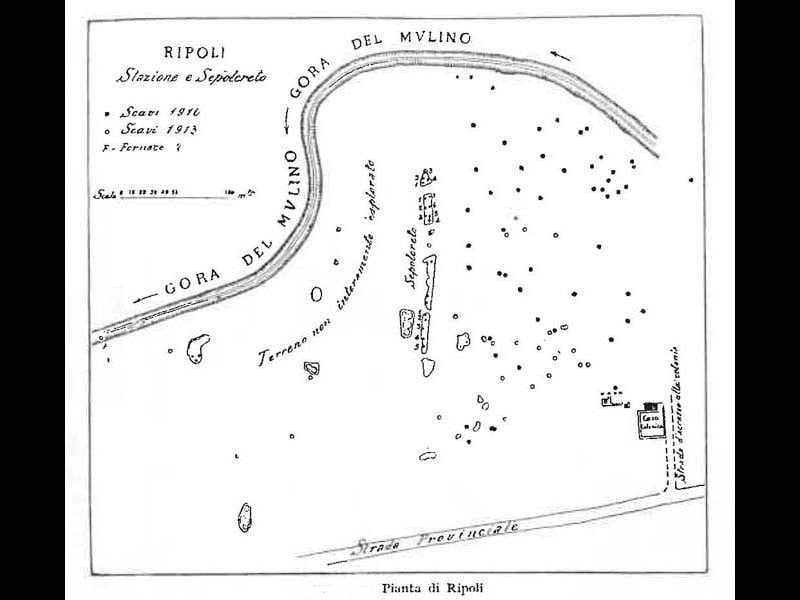

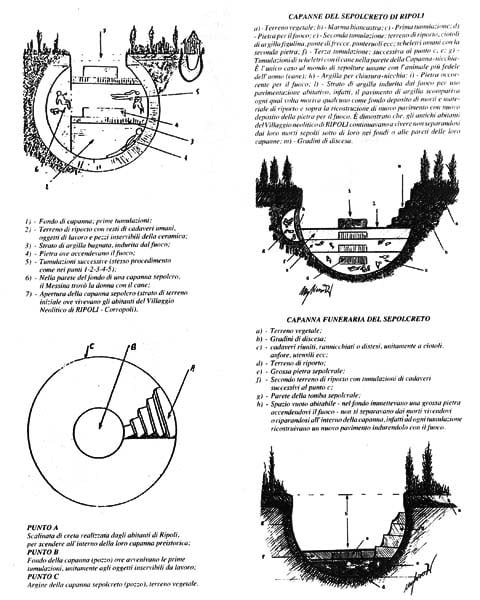

In 1910 Angelo Mosso made the first excavations but died before being able to publish a report on the work carried out. Other excavations were carried out in 1914 and 1915 by V. Messina who discovered 34 huts in the village, and a burial ground in the center of the village. Twenty years later his excavation journal was used by Rellini to write a monograph on the village of Ripoli which at that point of the excavations numbered 80 huts, as shown by a map conserved by the Museum of Ancona.

Ugo Rellini will trace a detailed picture of the culture of Ripoli and in particular a precise definition of the types of ceramic, in particular of painted pottery and of the characteristics of lithic production and will attribute the culture of Ripoli to the final phase of the stone age, i.e. to the Eneolithic. He considered the models of painted ceramics of oriental origin, but of local production and despite being very interested in Ripoli, "... he considers it just one of the groups of that substantially unitary cultural facies formed by painted pottery that we would now define as Neolithic... Rellini's opinion that has had the most influence on subsequent studies is that which makes the figuline pottery the guiding fossil of the culture of Ripoli, to which many stations were thus assigned, especially in the Marches, which lacked painted pottery and equally representative types ...” (Giuliano Cremonesi – The village of Ripoli in the light of recent excavations – Journal of Prehistoric Sciences – vol. XX 1965).

Pia Laviosa Zambotti (an internationally renowned self-taught scholar, with an extraordinary life, awarded by the Accademia dei Lincei for her main work "Origins and diffusion of civilization") in her 1943 text "The most ancient European agricultural cultures" reaffirms the attribution to the Eneolithic of Ripoli and makes it a particular facies of a "homogeneous" culture which would include in itself various techniques: from impressed ceramics to painted, to graffiti, to red monochrome. The author also insists in several points on the parallels between Ripoli and the Balkan sphere, in particular on contacts with Dimini. (Giuliano Cremonesi, 1965).

Only 50 years later, in the 60s, excavations resumed by the University of Pisa, under the guidance of Prof. Antonio Mario Radmilli and Prof. Giuliano Cremonesi, which led to the identification of 22 structures. With the numerous excavations conducted by Radmilli in Abruzzo it was overcome "… the excessive schematism of a periodization in clearly chronologically distinct facies and cultures and Rellini's opinion was still accepted, which considers the ceramic figulina acroma as a typical element of this culture. Again in 1959 Radmilli speaks of Ripoli-type achromatic figulina ceramics. From this derives the need to trace this culture back to a very ancient date whose most archaic moment would be documented by the villages of Fonti Rossi and Leopardi, the latter dated with 14C to 4600 BC, in which the acroma figulina pottery is associated with the pottery imprinted …” (Giuliano Cremonesi, 1965).

With the most recent excavations, the beginning of Ripoli moves even further back. In an article in the news of the Quaderni di Archeologia d'Abruzzo Andrea Pessina, Mauro Rottoli, Tiziana Caironi, Elena Natali state that on the basis of the 14C datings "… the beginnings of Ripoli are placed in the last centuries of the XNUMXth millennium BP, in a chronological space in which the Adriatic aspect of Impressed Ceramics fades to the North (as documented in Ripabianca of Monterado near Ancona), while this culture in the Abruzzo area appears to have already been largely precociously supplanted by the development, starting from 6.500-6.400 BP (Radi, Tozzi 2009), of the Catignano culture painted ceramic…”. Radmilli's profound interest in the village of Ripoli made a change in the vision that archeology had had up to then: in his oral communication at the VI Scientific Meeting of the Italian Institute of Prehistory and Protohistory held in Ancona in 1961 he gave a first definition of the culture, a definition that he will go on clarifying more and more, separating the culture of Ripoli from the uncolored ceramic figulina.

Radmilli had already introduced in his studies the concept of cultural current (already partially enunciated by Aldobrandino Mochi in 1915 but never actually taken into consideration), whereby prehistoric cultures were to be seen as concrete historical realities due to different communities which developed, on a common basis, different dynamics and durations with variable internal evolutions due to diversity of environmental and economic resources, contacts and exchanges.

Although Radmilli insists on its character of "culture", highlighting the many motifs of which it is composed, many scholars have insisted for a long time in defining that of Ripoli a "style", taking into consideration only the type of ceramic decorations.

Radmilli instead with five excavation campaigns - between 1960 and 1965 - clearly highlighted that it was a complex society, open to external influences, with motifs also coming from territories outside the Italian peninsula: a fusion of ancient and various cultural traditions with local elements, while others were the result of the evolution of indigenous types. Radmilli also owes the discovery that Ripoli had a very long history dating back to the Mesolithic: during the second excavation campaign, in fact, findings from the Upper Paleolithic came to light from the bottom of a Neolithic hut. Confirmation of a frequentation of the site dating back to 8000/7000 BC came with the more recent excavations of 2011, 2012, 2015 led by Andrea Pessina, Superintendent for Archaeological Heritage of Tuscany, with the discovery of a paleosurface referable to the Mesolithic, constituted from an intense concentration of Helix-type shells associated with lithic industry and faunal remains. A sign that they would exist”… Mesolithic camps of hunters-farmers who settled near a stream which, during its flooding, covered them with silt, sealing off a site of truly rare finds given its exceptional conservation. On this floor were found the remains of bones of hunted and stripped animals, shells and the remains of hunted and cooked turtles …” (Giuliano Cremonesi, 1965).

During one of Radmilli's campaigns a piece of a ditch was discovered: which is a peculiarity of some Neolithic villages of the central and southern Adriatic but whose purpose is not clear. “… On the basis of such scarce and incomplete data, any hypothesis on its function would be risky. On the other hand, this problem cannot be limited to the village of Ripoli, but must be framed in that wider complex which includes the trenches of the Matera and Sicilian villages and is therefore connected with the types of settlement due to particular needs common to a vast group of Neolithic peoples from central-southern Italy and the islands …” (Giuliano Cremonesi, 1965).

MATERIAL ASPECTS OF THE CULTURE OF RIPOLI

A fundamental work on the Culture of Ripoli was done by Giuliano Cremonesi, a pupil of Antonio Mario Radmilli. His first important work (specialization thesis at the Scuola Normale of Pisa), was the analysis of the culture of Ripoli based on the data of the excavations conducted from 1961 to 1964. He was able, by analyzing the materials of the individual structures, to define the evolution of a culture, traditionally enclosed within the Middle Neolithic with painted ceramics, highlighting its long duration and internal evolution which, from the classic painted ceramics of the initial phase, sees gradual changes up to the formation of an aspect that incorporates influences from Diana and Lagozza , elaborating them in what he later defined as the aspect of Fossacesia, which had in a certain way unified central Italy.

In his evolutionary scheme Cremonesi distinguished three different cultural phases characterized in fact by huts of different shapes in most cases of residential type.

Ripoli I it is characterized by kidney-shaped huts with an ellipsoidal profile while Ripoli II e Ripoli III they have circular huts, even double or multiple.

Each group of huts presents variations in the presence of the various types of ceramic, stone and bone artifacts. “… On the other hand it is extremely significant that in the first group many elements are absent which appear in the second and reach relatively high percentages in the third. Among these are the types that find comparison with specimens found in the Diana station or found in levels in which the culture of Ripoli is associated with that of Diana and Lagozza: the ollas, the ribbon handles with raised edges, the whole complex simple tubular handles or with various appendices. The truncated conical bowls with cylindrical necks, the careened vases and the ring-shaped internal handles also have a similar behavior. In the lithic industry there are no notable variations from one group to another as regards the percentage of each type; the only significant datum is offered by the very strong growth of obsidian in the third group. … Of the 34 huts described in the Messina report, 8 are upset, 18 are simple and of these 10 are circular, 7 oval and 1 has a defined “boiler” shape (i.e. with a narrow mouth and falling walls), 4 are double and another 4 are multiple … Ripoli was undoubtedly a center of considerable importance inhabited by a large nucleus and provided with economic resources such as to allow the execution of an imposing enterprise such as the moat – 7 meters wide and 5 deep – which required a rather evolved social organization and not indifferent collective work. The rather intense commercial relations with populations of other cultures seem to be another component that assumes a certain importance in the context of the economy of Ripoli ... further proof of the large commercial activity of the people of Ripoli is given by the widespread diffusion of their painted pottery ...” (Renata Grifoni Cremonesi – Ideological and funerary aspects in the culture of Ripoli and in central-southern Italy – Conference “The full development of the Neolithic in Italy” – Finale Ligure (SV) – 8-10 June 2009).

From the examinations of the faunal remains in the various huts, Cremonesi deduces that thanks above all to the positioning on river terraces favorable for crops: “… The economy of the civilization of Ripoli is mainly based on cattle breeding, while hunting represents a relatively marginal activity. The presence of millstones and sickles also attests to a large development of agriculture …” (Renata Grifoni Cremonesi, 2009).

The palaeobotanical studies on the remains found in the various sites have shown that in the village of Ripoli the following were cultivated: spelled or Triticum dicoccum, spelled wheat or Triticum monococcus (it is one of the first cultivated forms of wheat), soft wheat, Triticum aestivum and, as fundamental cereal, barley, Hordeum vulgare/distichum, but also lentils and peas.

Giusi Di Crescenzo - 2021

REFERENCES

- Giovanni Capellini – “The Stone Age in Val Vibrata” – excerpt from Memoirs of the Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna –1871;

- Giuliano Cremonesi – “The village of Ripoli in the light of recent excavations” – in Journal of Prehistoric Sciences – vol. XX 1965;

- Giuliano Cremonesi – The cave of the Pigeons of Bolognano in the context of cultures from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age in Abruzzo – Gardens 1976;

- Maria Antonietta Fugazzola Delpino and Vincenzo Tiné – “The clay female figurines of the Italian Neolithic. Iconography and cultural context” – in Bulletin of Italian palethnology – 2002-2003 – pp. 19-51;

- Marija Gimbutas – The civilization of the Goddess – edited by Mariagrazia Pelaia – alternative press/new balances 2012;

- Marija Gimbutas – The language of the Goddess – The Owls of Venexia – 2008;

- Renata Grifoni Cremonesi – “Ideological and funerary aspects in the culture of Ripoli and in central-southern Italy” – Conference The full development of the Neolithic in Italy – Finale Ligure (SV), 8-10 June 2009;

- Renata Grifoni Cremonesi and Anna Maria Tosatti – Rock art of the Metal Age in the Italian peninsula Location of sites in relation to the territory, symbols and interpretative possibilities – Access Archeology 2017;

- Renata Grifoni Cremonesi and Annaluisa Pedrotti – “Neolithic art in Italy: state of research and new acquisitions” – in XLII scientific meeting of the IIPP Prehistoric art in Italy. – Trento – Riva del Garda – Val Camonica 9-13 October 2007;

- Vicki Noble – The Double Goddess – The Owls of Venexia – 2005;

- Andrea Pessina, Mauro Rottoli, Tiziana Caironi and Elena Natali - "Ripoli Research in the Neolithic village" - in Newsletter of the Archeology Papers of Abruzzo 3/2011 ;

- Concezio Rosa – Studies of prehistory and history;

- Mario Improved – The prehistoric village of Ripoli –1990;

- John Robb – The early Mediterranean Village. Agency, Material Culture, and Social Change in Neolithic Italy – Cambridge University Press, 2007;

- Italico, Research center for making, conserving and enhancing art – “Ripoli, Culture, art and tradition of a civilization” – in Study papers, research and documentation - 1/2013;

- Pia Laviosa Zambotti – The oldest European agricultural cultures – Giuseppe Principato publishing house, 1943.