di Francesca Principi

The spiritual world of our most ancient predecessors is one of the most debated topics in the field of prehistoric studies: the sense of the sacred is a theme with elusive contours and the difficulties increase if prehistory is taken into consideration, a period where we have available only images, signs and, more rarely, artifacts, created in a time very distant from ours. As F. Facchini writes “homo religiosus it is not only that of burials or of the magical-religious art of the upper Paleolithic, but it is man as capable of symbolization, the'Homo symbolicus, which is not identified in a particular phase of hominization, but in being a man, capable of thinking, of reflected psychism, the man capable of grasping the manifestations of the sacred in the elements of nature, in what Mircea Eliade calls hierophanies, from the celestial vault to the elements of nature, everywhere man perceives something or someone that transcends him”. Nature itself, therefore, is a manifestation of the sacred and it is certainly from this perception that the idea, in prehistoric man, of a primordial female divine entity is born, the one we today call the "Mother Goddess" or "Great Mother". At an archaeological level, this is already confirmed starting from the Upper Paleolithic (40.000-10.000 years ago) and arises in relation to particular finds, the so-called Paleolithic "venuses", of representations of the female body in stone, mammoth bone, ivory and rarely clay, which since remote phases of the upper Paleolithic developed in almost all of Europe. Some have realistic shapes, others are just sketched and schematized, but almost all have similar and unmistakable characters: they usually appear naked and have the characteristic of having breasts, belly, buttocks and hips of accentuated dimensions. Usually the pubic region is also marked, while the head, arms and hands are only slightly visible; the feet are absent.

In many cases the dating of the statuettes remains uncertain as they are fortuitous discoveries, therefore occurring outside a stratigraphic context, but the chronological span they cover seems to be very broad: the oldest example that is known to date is represented by the Venus of Hohle Fels, found in Germany, and dated between 35-40.000 years ago; most of the Venuses, on the other hand, seem to come from the Gravettian culture (29.000-20.000 years ago).

Over time, numerous interpretations have been given regarding their meaning: from representations of steatopygian ethnic groups to the Paleolithic female ideal, up to idols connected to fertility cults. Today, the idea that these representations were related to a fertility or life-exaltation cult seems the most probable. This interpretation becomes even more evident if we think of how difficult it must have been for Paleolithic man to guarantee the continuity of his own species, in a world constantly threatened by the most varied pitfalls and crossed by the climatic rigors of the final phase of the last glacial period. Furthermore, from a historical-biological point of view, it is very probable that man, not having yet understood the process of reproduction and that is mating as the cause of pregnancy, should have attributed special, perhaps magical properties to the female being . Therefore those significant organs such as the belly, the breasts and in general the whole body which tended to grow and become prosperous in conjunction with pregnancy, ended up acquiring a sacred value, becoming the symbol par excellence of the regenerative capacity of nature itself.

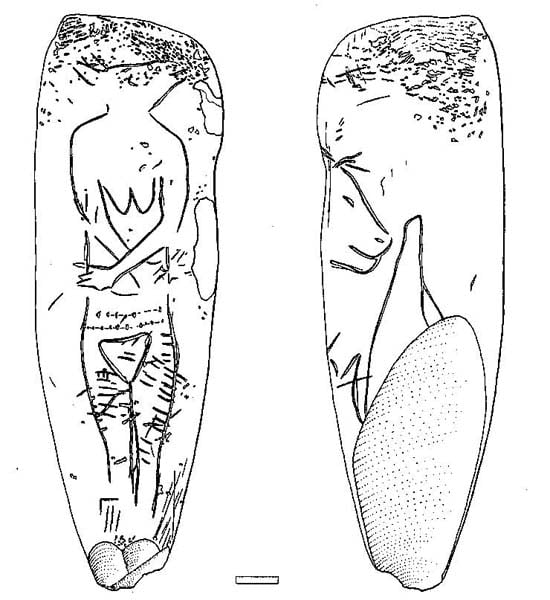

Also in the Marche area we have evidence of this type: one of the best known is the pebble of the Venus of Tolentino, found near Tolentino (MC) and dated to the Epigravettian (12.000/10.000 years ago). It looks like an elongated pebble of phthanite and has engravings on both faces: the front face is engraved with a female figure, in a frontal position, with the head of a herbivore placed in profile, probably a deer; on the back face of the pebble, on the other hand, the profile of a herbivore, probably a bovid, is engraved. As for the female figure, despite having been defined as a Paleolithic Venus, we see that in reality she does not present the typical exuberance of female traits: the only exceptions that refer to the iconography of Venuses are the marked pubic triangle and the hands resting on the belly .

Therianthropic figures, i.e. anthropomorphic with animal heads, have been known in the form of statuettes, paintings and engravings since the Upper Paleolithic but explicitly female figures are actually very rare. What could their meaning be? Perhaps they were mythological figures but the most accredited interpretation is the shamanistic hypothesis: by resorting to the ethnographic analogy it is possible to hypothesize that there was a corpus of spiritual and religious practices of a shamanic type, which also included ritual masking.

The Venus of Tolentino has a further peculiarity: on the belly of the figure there are two engraved horizontal lines crossed by a series of dashes, 6 and 10 respectively, the so-called "barbed wire" motif. It has been interpreted as a system of annotation, perhaps of counting, and it is entirely probable, given its arrangement on the belly of the figure, that they were instructions relating to female fertility cycles.

The second Venus found in the Marche area is the Venus of Frasassi, acquired in 2009 even if it is the result of a donation. This find comes from the Grotta della Beata Vergine di Frasassi (AN) and the raw material used is calcite, obtained from a stalactite, given that it would seem to confirm the autochthonous origin of the find; it has been dated to about 20.000 years ago.

The iconographic theme represented falls within the realm of Paleolithic Venuses, albeit with some distinctive notes: while presenting the typical accentuation of the sexual characteristics, the figure is rendered through a few schematic masses, furrowed by deep incisions. The back of the statuette is rendered in a very summary way and the detail of the buttocks is completely absent: perhaps the frontal view was the privileged one. On the head there are two lateral furrows and a horizontal posterior furrow, which separate the face from the mass of hair or, perhaps, from a headdress. A distinctive element is given by the unusual position of the arms, extended forward, which seems to refer to an attitude of prayer or offering.

As with other cases, the fact that it was found in a cave is significant. These places enjoyed a particular symbolic value: the fact of being isolated, obscure as well as their peculiar conformation that connects the outside world with the depths of the Earth, will have contributed to making them perceived as special. Gimbutas has proposed a correspondence between the peculiar conformation of the cave and the maternal womb, symbolically transforming the cave into the "womb of the Goddess", the place from which everything is born and to which everything returns: not surprisingly, the cave will also become a burial place .

Following the thread of time, in the Neolithic we have the flourishing and maximum diffusion of a very large variety of figurative and symbolic motifs which attest even more explicitly the veneration of a divine figure with feminine features. The transition from the cultural model of the Paleolithic to that of the Neolithic was not a break but rather a reworking of the old ideological and figurative forms that were incorporated into the new ones: in general, underlying expressive themes such as female fertility connected to the survival of the group survive , to which is added, with the new agricultural productive economy, an accentuation of the relationship with the fertility of nature. Furthermore, various animals, natural elements, signs, symbols are associated with the Goddess which create a truly varied iconographic and stylistic apparatus. As carefully documented by the work of the archaeologist Gimbutas “the central theme of the symbolism of the Goddess unfolds in the mystery of birth and death and in the renewal of life, not only human but of the whole earth and indeed of the entire cosmos. Symbols and images are grouped around the parthenogenetic Goddess and her fundamental functions of Giver of Life, Ruler of Death and, no less important, of Regeneratrix, and around Mother Earth, who is born and dies with plant life” (from the introduction of “The Language of the Goddess”, M. Gimbutas).

The so-called is inserted in the wake of the figurative heritage of the Paleolithic Venuses Venus of Fano, find that was donated to the National Archaeological Museum of the Marche without the discovery coordinates. Its authenticity still remains uncertain even if the formal canons of this statuette seem to place it in the Neolithic context.

The statuette, in grey-green stone, overall appears rather harmonious and proportionate with the exception of the hips and the upper part of the legs which are of accentuated dimensions: the belly, slightly prominent, also has the navel and is surmounted by two small breasts rounded under which are represented, barely perceptible, folded forearms. A novelty, in the back of the figure, is a disc-shaped element in relief on the back: it is difficult to say whether it could have a simple functional or rather symbolic value. The statuette has no head, instead of which there is a sort of appendix, where it is possible to suppose that the head could have been hooked.

Also to the Neolithic period belong the three clay figurines from Ripabianca di Monterado (AN), dated to about 6.200 years ago. They reproduce the schematized type of the naked female figure, according to the stylistic and iconographic canons proper to the art of the early Neolithic: the representation of the body is limited to the trunk and the neck, the head, the upper limbs are completely missing (reduced to two small prominences ) and the lower limbs. The only anatomical detail to be represented is that of the breasts, plastically rendered with two small protuberances. This typology of statuettes appears to be particularly widespread in the areas of the ancient Eastern Italian Neolithic and in the Balkan area, with different typologies although all attributable to a very simple and schematized iconography of the female figure.

According to many authors, these statuettes symbolize both the idea of female fertility of Paleolithic derivation, and that of mother earth's own fertility: what is highlighted is the breast, which embodies the female potential to be a source of nourishment and therefore, symbolically, divine source. It is interesting to note that the context of the discovery of this kind of statuettes is normally connected to residential contexts, sometimes they are even found intentionally placed under the floors of the houses, as a foundation rite: it is therefore probable that they also had a protective function towards the home and the domestic productive context.

At the end of the Neolithic there were significant changes in the economic and social system, which also led to a change in the spiritual/religious system: at an archaeological level we are witnessing a progressive disappearance of female figures which are supplanted by representations of men in arms, scenes of life collective, solar symbols, to which a new ideology corresponds. The Goddess will be gradually ousted but despite this she will continue to be venerated, albeit in a different form: in later times she will take on different denominations, according to the ethnic group or the place in which she will be venerated, and her many aspects will be dismembered and attributed to single female divinities, each with its own peculiarities. The divine essence of the prehistoric Mother Goddess, therefore, will continue to live in the guise of other later female divinities, through a phenomenon of religious syncretism.

And of this, as far as the protohistoric period is concerned, the goddess Cupra, the only known female deity of the pantheon piceno, where by Piceni we mean that set of populations that inhabited part of the Marches and Abruzzo approximately between the XNUMXth and XNUMXrd centuries. BC As evidence of the existence of the goddess Cupra we have both written and material sources and various classical authors tell us of an important sanctuary dedicated to this deity, along the Adriatic coast: although its possible location still remains controversial, there is unanimous opinion that the sanctuary of Cupra should be of considerable importance in central Italy and beyond. An important emporium probably stood near it which became a place of meeting and exchange, both economically and culturally, for the populations arriving from the Adriatic and the trans-Apennine routes.

As far as the identity of this divinity is concerned, important evidences are the four engraved small plates coming from Colfiorito di Foligno, as well as an inscription, again on a bronze plate, coming from Fossato di Vico, on the Umbria-Marche border, where the name of Cupra is associated with the eloquent epithet of mater. Another interesting element is that these plates seem to have originally been applied to water containers (those of Colfiorito to water containers, that of Fossato di Vico to a curb of a cistern), thus highlighting the of goddess worship with water.

Various other interpretations have been given on the definition of the identity of the goddess Cupra: there are those who have compared her to the Latin Bona goddess, an ancient mother goddess of Lazio origin, on the basis of the indications given by Varrone, who explains that the term Sabine cyprus corresponded to the Latin bonus, thus basing the juxtaposition between the two goddesses on an onomastic correspondence. Strabone instead reports that Cupra was the name given by the Etruscans to the Greek goddess Hera, mother of all gods. A further combination was made with the Greek goddess Aphrodite who, with the name Cypria, we know had a well-known sanctuary on the island of Cyprus: in this sense, a possible Cypriot origin of the goddess Cupra cannot be excluded, which may have been introduced on the Picene coasts by traders or Cypriot exiles, present in the Adriatic since the XNUMXnd millennium BC Finally, there is also a passage by Asinius Pollio where Cupra is defined Venus antistita that is, "priestess of Venus", the Roman counterpart of the Greek Aphrodite, a description that once again establishes the close correlation of the two goddesses. Cupra, therefore, fits fully among the heirs of the divine essence of the prehistoric Mother Goddess, demonstrating the survival in the protohistoric field of some peculiar aspects of her, first of all that of goddess of fertility.

Taking a long leap forward over the centuries, one of the most recent examples of this process of religious syncretism is that of Black Madonna of Loreto, whose sanctuary rises precisely in Loreto (AN) and whose cult is very popular in Italy and beyond.

The diffusion of images of Black Madonnas in the West is very ancient: it is often associated with the East and in Europe, in particular, they seem to appear between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries. although the cult seems to be much older than the documentation that has come down to us. According to some authors, the origin of the Black Madonnas must be sought in the ancient pre-Christian religions, in particular in the cults of ancient Middle Eastern and Asian black deities, such as for example Cybele, the Magna Mater Anatolian who was venerated in the form of a black conical stone, and Isis, mother divinity of the Egyptian area. Also in Greece several goddesses had appellations connected to darkness, for example Venus was called "the black one", Artemis was "the dark one": in short, the sacred use of black to represent divine images was widespread. The darkness embodied by these divinities could have a double meaning: if on the one hand black is the symbol of dissolution linked to the deadly aspect of the divinity, on the other hand this color has always had a positive meaning in numerous cultures, becoming a symbol of life. According to ancient cosmogonies it was the color of universal synthesis, since it contains within itself the double aspect of absence and presence of everything and, as such, it embodied the archetype of the Principle, the matrix color from which everything originates: black, as chaos and beginning, it therefore contains a generative and fruitful potential.

Surely it is no coincidence that the Black Madonnas have always been highly venerated and invoked in the popular sphere for events concerning life, death, healing, protection, as evidenced by the numerous ex voto which can still be found today in the sanctuaries dedicated to them. In this regard, the custom is very interesting, which spread in the Marche from the seventeenth century. until the beginning of the last century, to place a small statuette depicting the Madonna of Loreto with the child outside the house: this custom was found to be widespread mainly in rural areas, but some examples are also present on city buildings. The statuettes were placed above the entrance to the house or in any case on the main front, always in places where they could be well noticed by everyone. This particular arrangement of theirs implies that different meanings were attributed to the object: in fact, although they represented the Madonna, the statuettes ended up having more of a magical and exorcistic meaning than a Christian one, as if to protect the family environment from the evil that could come from the outside world. external. Their function, therefore, could in part echo the one that prehistoric female statuettes also had: in this way, through a sort of underground current, the spiritual world of our more remote past is reunited with that of our present.

Francesca Principi

Adapted from "In the footsteps of the great mother” – cycle of meetings of the Margaret Fuller Women's Culture Center in Pescara – January-June 2005.