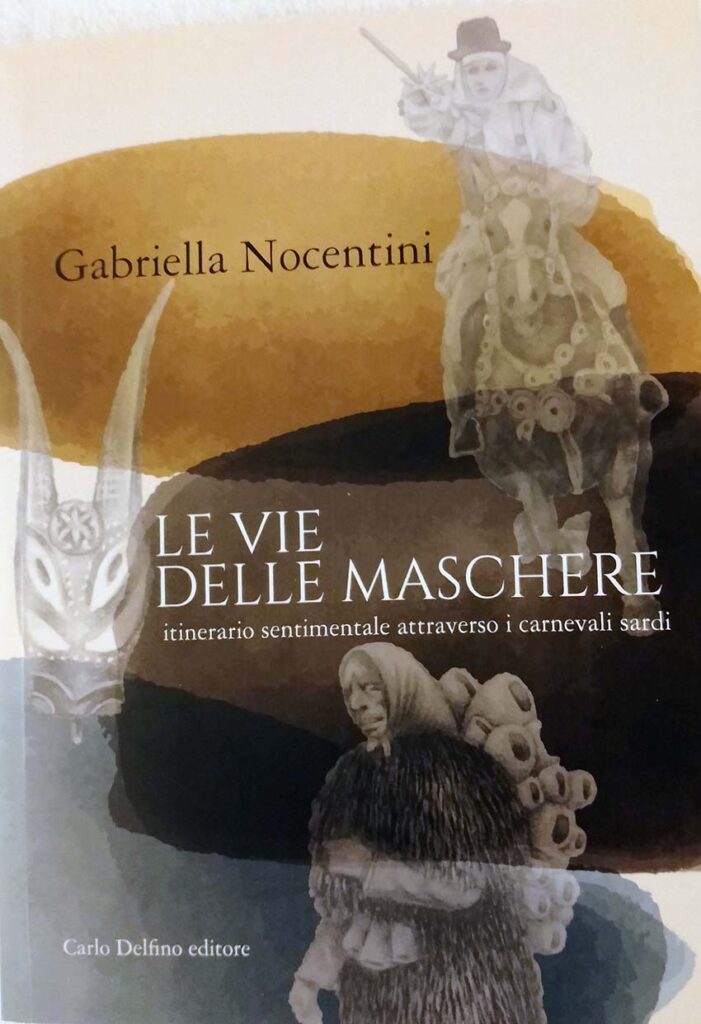

The ways of the masks. Sentimental itinerary through the Sardinian carnivals of Gabriella Nocentini

Carlo Delfino Publisher - Sassari 2021

In Sardinia you can still see traditional carnivals, which reveal a very complex world that is lost in the mists of time, bringing us back to the very ancient rites of fecundation, of passage from winter to spring, experienced throughout the Mediterranean basin.

I delved into 11 carnivals[1] among the best known, described chronologically as I have seen them over the years. But I don't limit myself to this, on the contrary, the strong emotions that gave rise to a reflection on myself, on my experiences, were born from this study. They were first of all a real inner journey. Digging up the ancient and magical roots of Sardinian civilization was also an existential quest for me, a retracing of my life. I wondered what prompted me to write about these violent, irrational and primitive carnivals. I thank them for everything I discovered through them and for what I recognized in myself. These representations impacted my reflections on death. It seems to me that I can say that they have allowed me to bear the losses that have struck me and that have forcibly changed me.

A book that reveals many faces.

Sardinia has an archaic quality that still today indicates it as one of the most conservative Italian regions: it is extraordinary how these real ceremonies have reached us, which cross the theme of the sacred, sometimes primitive and violent even in fiction. We are not faced with amusement, with Bacchic transgression, to understand each other they do not refer to the Roman Saturnalia or the Middle Ages and, even where it is possible to find traces of them, they are stratifications on something much more primitive. They are often gloomy, mournful ceremonies. The same term carresaw "carnival" means meat to be cut into pieces, to be dismembered. Square it is not the meat of the butcher's shop, but the human "living flesh" (Turchi 2011 [1990], 103).

These manifestations are very different from town to town, but the matrix is always the same and not always perceptible: the cult of Dionysus (Ivi,10), the god of vegetation, fertility, death and rebirth. In the ancient winter festivals commemorating the god's passion and death, followers of Dionysus tore alive young kids and young bulls because the myth said that he had been torn to pieces by the Titans while he was transformed into a bull (Graves 1977 [1955], 128). Primitive peoples created myths to solve mysteries to which they had no answers. The sacrifice and dismemberment of the god were necessary for many peoples for the earth to cease its state of winter death and for the seeds to germinate again.

Traditional Sardinian carnivals capture the tragic aspect of mourning. Rites which however in Sardinia were grafted on to something pre-existing which concerned the cult of the Great Mother, whose archaeological evidence abounds.

Dionysus, presumably arrived with the Mycenaeans in the centuries 1500-1200 BC (Lilliu 1977 [1967], 160), a multifaceted god with many names, is a complex and ambivalent divinity, male and female, adult and child, man and god. He represents strength and life energy. The gifts of nature, fertility and even culture depended on him, just think of the theater. The aspect that interests us here is that of the god of rain, vegetation, death and rebirth, known in Crete as Zagreus (Graves 1977 [1955], 147)[2].

One of his appellations was Mainoles, the madman, the one who wishes to be possessed by the god (ibid., 128). This word explains the etymology of Maimone[3] name with numerous variations of the Sardinian mask dressed in skins and with horns.

The Dionysus/Maimone Sardinian is above all a rain god, it was the water that was asked for in a land that has always struggled with drought. It is significant that certain prayers were used until the thirties of the last century.

In Dionysus it seems to me that I can identify a bridge between the matriarchal and the patriarchal world, the former destined to be set aside, stemmed and controlled by the latter. There is no lack of points of reflection on this in the masks, such as the indispensable female element that we find in all masks, that is on cowherd, the woman's handkerchief on the head, necessary for men (the masks were always male) to take upon themselves the fertility that women have by nature. Or even as in the Sartiglia of Oristano: three women/magicians sew in silence on the on Componidori (the hero, the god of the day) women's clothes: a shirt of lace and ribbons, a bridal mantilla, a camellia on his chest and finally they put on him the hieratic mask with a feminine expression. A very complex preparation and reference to the studies of Tilde Giani Gallino (1986) on female archetypes in male culture as regards the figure of the fertilizing hero.

In these ceremonies, it is necessary for the hero to be cloaked in that true fertility that only women have and that only an accentuated female image can validate. One question is spontaneous: isn't this where the very great power that men have taken over women comes from? From there to being submissive the step is short.

The masks are full of symbols, some of which are very difficult to read, others less so. Certainly today gestures are repeated without understanding their meaning. Yet what little has arrived is capable of still resonating. In Ollolai, sos Turcos or Truccos, they have on their shoulders the embroidered red shawl that was used for the baptism of the newborn, on their faces the white veil used to cover the dead on the bed. Death and birth: the signs have been maintained. At Sarule, sas Mascheras in Gattu they have on their heads a white blanket from the cradles of children, on their faces a black veil that represents death. In Fonni, sas masks limpias, today they have many doilies on their heads, but once upon a time they used baby linen.

Several carnivals, however changed and become folklore, continued until the Great War. Then in part they began to get lost, even if they resist in the internal localities, even in Mamoiada and Ottana uninterruptedly up to today. The First World War interrupted the life of the agro-pastoral world which never confronted itself with the outside world. With the strong emigration from the second post-war period to the seventies and the mass schooling, people moved away from the language, from the shepherd's dress... and from traditional carnivals. Television completed the picture. Tradition is condemned to disappear, considered a product of ignorance and misery.

A millennial isolation ceases. Here it is interesting to say that a homogenization begins which has changed daily life in a very significant way too (Gallini 1977, 127-133). However, in this specific case, cultural associations have also recently recovered ancient masks, aided by interviews with the elderly, documents and studies on the subject, right hand in hand with the end of the agro-pastoral world. It is significant that it was often young people who rediscovered them and not for a mere commercial discourse, I can assure you, given that almost always, if you take away the best-known carnivals, I was the only one not in the country, but for a much more complex discourse than identity research and construction. A "genuine need" as Gallini noted since the seventies (Ivi 1977, 135). This aspect alone deserves a separate study, the most delicate point of which becomes the recovery of the past and the contradictions of a globalized present.

Gabriella Nocentini

The ways of the masks. Sentimental itinerary through the Sardinian carnivals, Carlo Delfino Publisher, Sassari, 2021

[1] I saw the carnivals mentioned in the following places and dates: Aidomaggiore (Ash Wednesday 2018), Ardauli (last Sunday 2016, masks recovered from the youth group S'Intibidu in 2014), Austis (Sant'Antonio 2016, masks recovered from the cultural association SOS Colonganos in 2006), Bosa (shrove Tuesday in 2009 and 2011), Fonni (last Carnival Sunday 2016), Gavoi (shrove Thursday 2011), Lula (last Sunday 2016, masks recovered from the spontaneous Group SOS Cumpanzos de Su Battileddu in 2001), Mamoiada (Sant'Antonio 2012), Ollolai (Saturday of the pot 2009), Orani (Sant'Antonio 2017, recovered from the Group Association On Bondhu at the end of the nineties), Oristano (shrove Tuesday 2009, last Sunday of carnival 2011), Ottana (last Sunday of carnival 2016).

[2] Crete, in the XIII century. BC, Dionysus was considered the son of Zeus who had united with Persephone in the form of a snake. Persephone was his daughter having been born of him and Demeter. Two very archaic elements are therefore found in the most ancient myth of palatial culture: the snake and incest. One of the many names attributed to Dionysus was Chthonios, the subterranean, linked to the cult of the dead because his mother was the queen of the Underworld (Graves 1977 [1955], 66).

[3] Originally Mamutones indicated the masks of the Sardinian popular carnival while Maimones were more properly the masks reproducing diabolical features (Moretti 1954, 179). Maimone was a diabolical being (Alziator 1956, 49). Maimone or mamussone was a puppet used to frighten children, even a worthless man (Wagner 1962, 61-62). Maimone was a demonic being who brought rain (Lilliu 1980 [1967], 161). Maimone corresponds to a rain deity of proto-Sardinian origin, reinterpreted by the Phoenicians (Ligia 2002, 71-75). Maimone and Mainoles have the same origin as maimasso or maimatto, furious, violent (Turchi 2011 [1990], 21).