di Julia Goggi

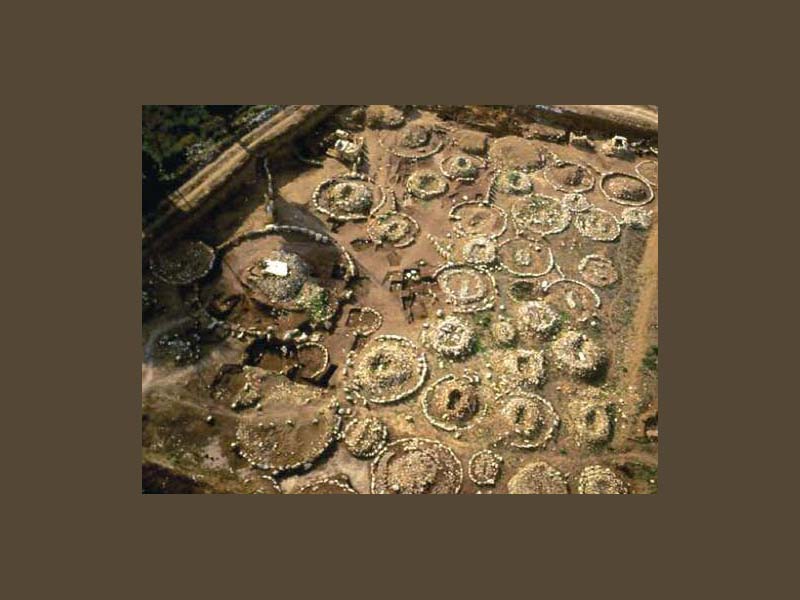

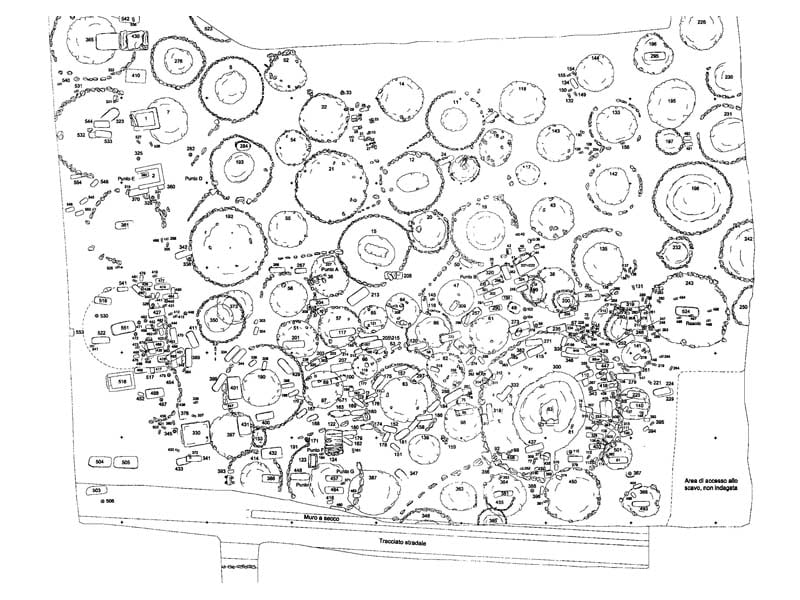

Fossa is a site in the province of L'Aquila, generally referring to the Sabellic population of the Vestini, whose first evidence dates back to the mid-XNUMXrd century BC. C. thanks to a coin legend in which VES appears in a series of aes grave also adopted in other centers on the Adriatic side[1]. The necropolis is located in the L'Aquila basin on the northern banks of the Aterno river, an alluvial plain which has led, over the years, to the formation of an underground more than three meters thick such as to allow perfect maintenance of the burials. The first traces of attendance date back to the Bronze Age (1700-1350): several fragments of clay pottery found sporadically in the excavation area are attributed to this period.

The settlement to which the necropolis refers, in use during the Iron Age, is located in Monte del Cerro[2]. Different types of tombs have been found: circle tombs with crepidine (i.e. bases) of stones; stone mound tombs without delimitation or only sketched out; shallow graves with or without stones; children's pit tombs with wooden protection, with deposition of the deceased in tiles; simple pits, pits bordered by stones, or with a caisson.

To understand the costume of the women of Fossa in the so-called Orientalizing period (between the end of the eighth century and the beginning of the sixth century BC), the grave goods from the burials are important testimonies: being the tombs of "closed" contexts (the grave goods they are no longer handled once the burial chamber is closed) unless there are any and (unfortunately) rather frequent violations in later times, thanks to these objects we are able to understand or at least imagine what could be the way to decorate women's bodies middle-upper or very high class of Fossa in that period.

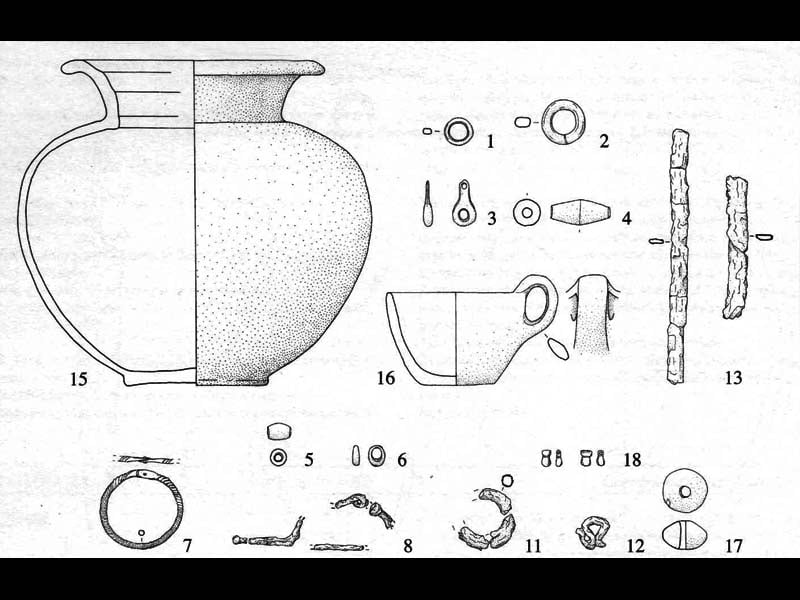

Beads (beads) and pendants are indicators of the presence of necklaces, often in bronze but also examples in amber (tombs 198, 36, 47), in glass paste (tomb 141), in iron (tomb 373); in some cases, iron nails have also been found, attributed to the fastening or decoration of the pendant (tomb 47). Observing the dating (late 198th century for tombs 141 and 36; first half of the 47th and late 373th-early XNUMXth century respectively for tombs XNUMX and XNUMX and XNUMX), one might think of a preference for simpler materials for the more recent ones, but the possibility of personal choices cannot be overlooked.

These burials are quite rich in materials, with the exception of tomb 36 which, however, has a certain amount of bronze and amber vagues of different shapes[3]; moreover here, under the skull of the deceased, an iron braid-holding spiral and an iron element with a flattened section were found: the latter could be interpreted as what remains of a diadem, according to a custom recognized for tomb 9 from nearby Loreto Aprutino dated between the end of the XNUMXth and the beginning of the XNUMXth century BC. c.[4].

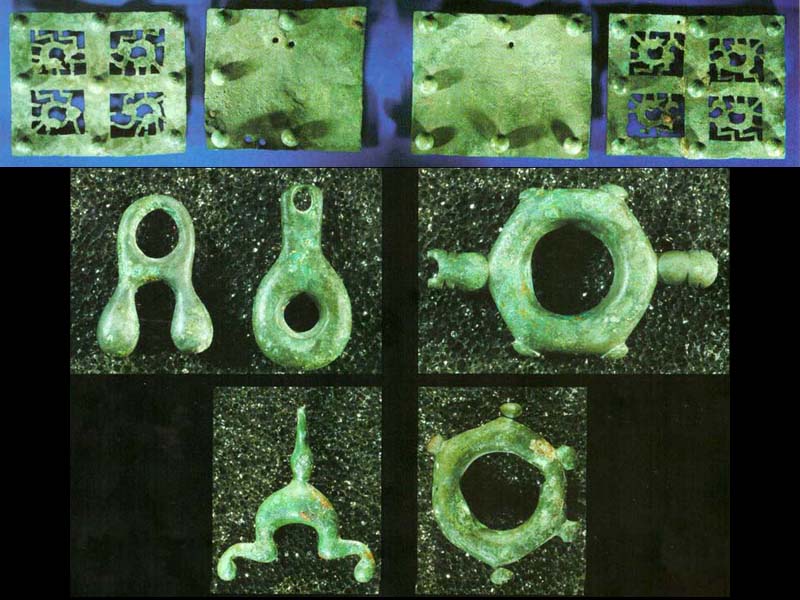

A certain variety is also attested in the fibulae: those found at the height of the femur or between the lumbars could perhaps drape or fix the skirt or its decoration to the dress, those found at the shoulders probably fixed a cloak, those found on the chest in addition to closing the dress and the neckline, they could support a jewel (as demonstrated by the remains of the bronze damascening of the specimen from tomb 36).

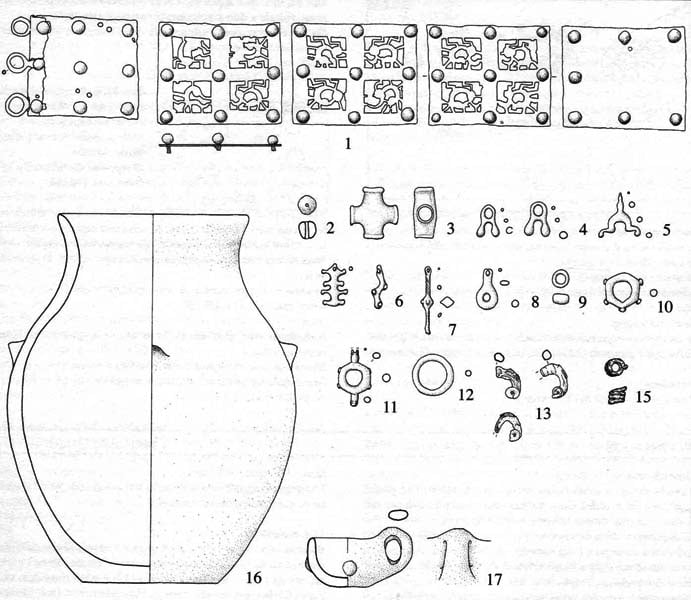

And also the remains of belts and belts: generally bullet plates or omega hooks: the latter (together with small nails) were functional for fastening the leather or fabric which formed the basis of the accessory. From tombs 47, 139, 334, 373 come belts with inserted bullets; in the case of tomb 198 there is a belt with embossed-decorated rectangular foil, while in tomb 387 there is a belt with embossed-decorated foil[5]. According to researches[6] the use of belts in Fossa began in the mid-eighth century BC. C. but consolidates in the Orientalizing Age. The type of belt found in tomb 198 is defined by Raffaella Papi as "jointed plates"[7]. The belt "with bullets attached", otherwise called "Capena type", consists of a rectangular leather band with applied ornamental tacks and perforated or full bronze end plates; the name itself indicates a Tyrrhenian origin, interpreted as a production inspired by Capena.

There are some armillas (bracelets) and rings in bronze or iron, both of simple workmanship or with overlapping ends; tomb 141 (infant) yields some digital rings with three-winding spirals, one of which is decorated with engraved dashes (this burial is rather unique because it has a fairly rich kit with glass paste beads inside). The discovery of a suspension ring, about 3 cm in diameter, at the basin from tomb 139[8] (which belonged to a woman between 20 and 30 years old) dated between the end of the XNUMXth and the beginning of the XNUMXth century BC. C. may suggest its use to hang a decorative element from fibulae on the body, perhaps pendants or a connection between a fibula at the height of the chest or the diaphragm and the belt placed on the pelvis.

It is possible that the vague, pendants and metal spirals found at the height of the legs embellished the clothes as they were probably sewn to the fabric.

The braid-holding spirals near the head may suggest that the habit was to gather the hair in a long braid, or two braids – if we are inspired by the aforementioned reconstruction of tomb 9 of Loreto Aprutino.

An important iconographic documentation is given by the "Lady of Capestrano": a fragment of a female torso carved in limestone and found under the head of the Warrior of Capestrano, with which it probably shares the dating to the XNUMXth century BC. C. Despite the fragmentary nature of the statue, archaeologists have managed to hypothesize that her left arm was raised towards her body in the act of squeezing the pendant of the necklace between her fingers, while her right arm was probably dropped until it bent in line with life[9].

The woman depicted in the statue was probably wearing a light garment, the breasts, bust and arms were covered by a bodice with long sleeves and down to the waist. The bodice was decorated in the upper and lower part and on the edges of the sleeves by a band in relief probably red; this is also reproduced in the shoulder straps that anchor the bodice and to which two large fibulae with a meandering arch decorated with trapezoidal pendants, also red, are fixed; red is also the ornament that the lady wears around her neck, perhaps a reference to the use of amber.

In correspondence with the shoulder blades, the bodice is covered by a quadrangular element on which a long braid seems to fall. Even if the lower limbs are missing, in this case it has been hypothesized that they were covered by a long skirt of which the upper flap on the back has been identified. Her hair was tied back and covered by a veil that spread over her shoulders.

The hypotheses made on the dress of the Lady of Capestrano are archaeologically demonstrated by the findings of the necropolis of Farina-Cardito di Loreto Aprutino, in particular from tomb 9. For the costume of this burial a costume composed of a veil surmounted by a diadem has been hypothesized in iron decorated with 13 amber bezels. Probably the dresses worn were those for parades, embellished by the entire set of jewels that the deceased possessed, testifying to the wealth of the woman and her family.

Why is it useful to understand Fossa's fashion in the Orientalizing age? It helps us understand a lot about these women's lifestyles and their hypothetical status. In the vestino environment the ceramic kit does not appear to be particularly articulated. It has been assumed that the reason for this phenomenon was due to the fact that the role of women was more closed and humble and that they did not hold prominent social roles as instead happened in other areas[10]. In Etruria, for example, in the Orientalizing period it is believed that the woman covered the role of "progenitor and guarantor of the continuity of the group and of the lineage, within the ambit of a probable system of bilinear descent, for some women of the aristocracy custodians of particular powers and prerogatives"[11], in spaces that go far beyond just the domestic environment and concern the sacred and cults.

Anna Maria Bietti Sestrieri in one of her contributions released in 2009 enhances the roles of female power in the sacral sphere and in the production of ceramics by analyzing the necropolis of Osteria dell'Osa for the Lazio period II (late X-IX century BC), where hypotheses in the archaeological field have been supported by a careful anthropological analysis. According to the scholar, it is possible to identify a series of prerogatives as a clear manifestation of power: for example some specificities in the treatment of the body, the presence in the pottery of objects with a ritual value or of attributes such as the meat knife (an instrument connected to sacrifice and to the offering to the deity as well as obviously to the division of the meat). This has allowed us to hypothesize that the women buried in these burials were priestesses[12]. A social importance attributed to women also seems to be recognized in Homer, as Momolina Marconi also affirms: "So the social life in Homer, and I refer to the precious studies of Patroni, continues by custom to recognize the superiority of women, also of the Woman with a capital letter [...]”[13]. It is presumably not a reference to the Amazons, as there do not appear to have been all-female communities dedicated to warfare[14].

It therefore seems difficult to think of a more marginal role for the women of Fossa in the light of what has just been said, and of the contacts and cultural influences that took place between the various communities in those centuries; although we must not forget that each group had its own habits and traditions, its own practices and rules in terms of sociality.

Footnotes

[1] Ezio Mattiocco – fortified centers vestini – Teramo 1986 – p. 9.

[2] Vincenzo D'Ercole - "Protohistory in the Plain of L'Aquila in the light of the latest discoveries" - in Vincenzo D'Ercole, Roberta Cairoli (edited by) - Archeology in Abruzzo. History of a pipeline between industry and culture – Archaeological Superintendency of Abruzzo – Tarquinia 1998 – pp. 13-22.

[3] Vincenzo D'Ercole and Enrico Benelli – Fossa necropolis. Orientalizing and archaic kits – Celano 2004 – p. 20.

[4] Nuccia Negroni Catacchio - "The sumptuous robes" - in AA. VV. – Scripta Praehistorica in honorem Biba Teržan, Ljubljana – 2007 – p. 545; Andrea Staffa - "Vestini Trasmontani" - in Luisa Franchi Dall'Orto (edited by) - Pinna Vestinorum and the Vestini people – Chieti 2010 – p. 17.

[5] Vincenzo D'Ercole and Enrico Benelli – Fossa necropolis. Orientalizing and archaic kits – Celano 2004 – p.160.

[6] Vincenzo D'Ercole, Serena Cosentino and Gianfranco Mieli – Fossa necropolis. The oldest evidence – Celano – 2001.

[7] Raffaella Papi – “Villanovian in Abruzzo? Preliminary note on the female belts of Abruzzo in laminated bronze" - in Domenico Caiazza (edited by) - Safinim. Studies in honor of Adriano La Regina – Pedimonte Matese 2004 – pp. 95.

[8] Vincenzo D'Ercole and Enrico Benelli – Fossa necropolis. Orientalizing and archaic kits – Celano 2004 – p. 55;

[9] Nuccia Negroni Catacchio - "The sumptuous robes" - in AA. VV. – Scripta Praehistorica in honorem Biba Teržan, Ljubljana – 2007 – p. 539-540.

[10] Nuccia Negroni Catacchio - "The sumptuous conscientious" - in AA. VV. – Scripta Praehistorica in honorem Biba Teržan, Ljubljana – 2007 – p. 545.

[11] Mariassunta Cuozzo and Alessandro Guidi – Archeology of identities and differences – Rome 2013 – p. 87.

[12] Anna Maria Bietti Sestieri – “Domi mansit, lanam fecit: Was that all? Social status and roles of women in the first Lazio communities (IIth-9th BC)” – in Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology - 21 - I - 2009 - pp. 133-159.

[13] Momolina Marconi - "From Circe to Morgana" - in Reports of the Royal Lombard Institute of Sciences and Letters 1940-41 – collected in A. De Nardis (edited by) – From Circe to Morgana. Writings by Momolina Marconi – Rome 2009.

[14] Jeannine Davis-Kimball – Women Warriors. The Shamans of the Silk Road – first ed. 2002 – Rome 2009.

Julia Goggi - 2022

REFERENCES

- Vincenzo D'Ercole (edited by) - The Vestini between L'Aquila and Onna – L'Aquila 2013;

- Ezio Mattiocco - Vestini fortified centers - Teramo 1986;

- Vincenzo D'Ercole - "Protohistory in the Plain of L'Aquila in the light of the latest discoveries" - in Vincenzo D'Ercole, Roberta Cairoli (edited by) - Archeology in Abruzzo. History of a pipeline between industry and culture – Archaeological Superintendence of Abruzzo – Tarquinia 1998;

- Vincenzo D'Ercole and Enrico Benelli – Fossa necropolis. Orientalizing and archaic kits – Celan 2004;

- Nuccia Negroni Catacchio – “The sumptuous dresses” – in AA. VV. – Scripta Praehistorica in honorem Biba Teržan, Ljubljana –2007;

- Andrea Staffa – “Trasmontan dresses” – in Luisa Franchi Dall'Orto (edited by) – Pinna Vestinorum and the Vestini people – Chieti 2010;

- Vincenzo D'Ercole, Serena Cosentino and Gianfranco Mieli – Fossa necropolis. The oldest evidence – Celano – 2001.

- Raffaella Papi – “Villanovian in Abruzzo? Preliminary note on the female belts of Abruzzo in laminated bronze" - in Domenico Caiazza (edited by) - Safinim. Studies in honor of Adriano La Regina – Pedimonte Matese 2004

- Nuccia Negroni Catacchio - "The sumptuous conscientious" - in AA. VV. – Scripta Praehistorica and honorem Biba Teržan – Ljubljana 2007;

- Mariassunta Cuozzo and Alessandro Guidi – Archeology of identities and differences – Rome 2013;

- Anna Maria Bietti Sestieri – “Domi mansit, lanam fecit: Was that all? Social status and roles of women in the first Lazio communities (IIth-9th BC)” – in Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology - 21 - I - 2009;

- Momolina Marconi - "From Circe to Morgana" - in Reports of the Royal Lombard Institute of Sciences and Letters 1940-41 – collected in A. De Nardis (edited by) – From Circe to Morgana. Writings by Momolina Marconi – Rome 2009;

- Jeannine Davis-Kimball – Women Warriors. The Shamans of the Silk Road – Rome 2009.