di Elvira Visciola

What kind of cult of the dead did the Neolithic populations of Grotta Scaloria practice?

A study published in 2015 in the journal Antiquity has brought to light probable ancient funeral rites in use over 7000 years ago among the populations who inhabited the south-east of our peninsula, rites carried out within Scalaria cave located between the Tavoliere Dauno plain and the Gargano massif, located about 45 meters above sea level (entrance to the cave). Since the 50s, the Tavoliere delle Puglie has made headlines as the most important scenario of the European Neolithic: a series of aerial photographs taken by the Royal Air Force in 1943 have allowed the discovery of almost 1000 Neolithic settlements dated mostly to the 70th millennium BC scattered throughout the territory; subsequently the excavations carried out in the XNUMXs confirmed the presence of a dense settlement of small groups dedicated above all to agriculture and cattle breeding.

Archaeological research inside the cave took place several times over a long period of more than 80 years.

The cave was discovered by chance in 1931, during the works for the construction of the stretch of aqueduct between Manfredonia and Monte Sant'Angelo and subsequently explored by the archaeologist Quintino Quagliati who soon revealed the great importance and richness of the archaeological deposit.

At the time, in 1936, only the upper part of the cave, named Camerone Quagliati, was explored, signaling the presence of numerous human bone fragments as well as prehistoric pottery and stone tools. The bone finds led Quagliati to indicate the use of the cave also as a place to bury the dead, while the two-tone style of the ceramics was defined as the "Scaloria Alta" style, i.e. a ceramic figurine with red bands bordered by black lines with meander, hook, solid color decorative motifs, later also found in other Apulian sites dating back to the Middle Neolithic.

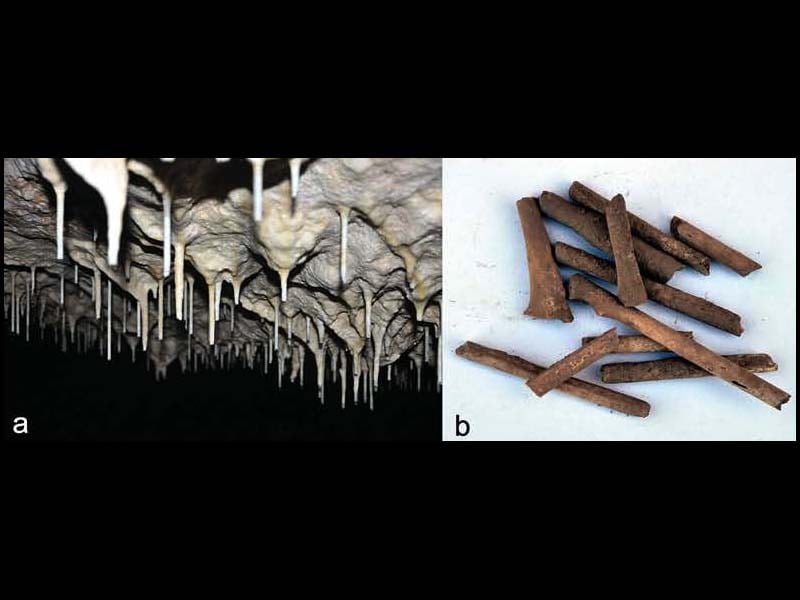

In 1967 a group of speleologists from Manfredonia discovered a further portion of the cave, the one defined as the Lower Chamber of Scaloria, which can be reached through a narrow and winding tunnel where numerous groupings of vases, over 40, cemented on the rocky floor or encrusted with the stalagmite formations. The archaeologist Santo Tinè, who was the first to carry out a systematic exploration of the cave, indicated the Lower Chamber as the seat of a cult, finding the remains of a religious ritual from the Neolithic era connected to the "cult of water”, a testimony that has remained practically unchanged for over seven thousand years. Tinè describes the cave: “... a large chamber (about 80 x 100 m) which was originally accessed from an entrance, which must have been formed after the collapse of a portion of its vault. The formation of the cave is of the so-called interlayer type, i.e. due to the void that must have been generated between two layers of limestone which separated following a tectonic movement or due to the erosion of the interlayer materials. This void, which slopes from north to south following the inclination of the calcareous layers, is very extensive horizontally, but varies from a few centimeters (and therefore unusable) to no more than 2 meters in height, which it reaches only in a few points. Generally it does not exceed one meter and is therefore with great difficulty made even more acute by the formation of concretions that adorn the vault and the floor ...”. The use of the room as a place of worship has also been confirmed by the presence of traces of a hearth near the vases and by the presence of a pool of natural water about 3 meters deep. It has been hypothesized that the cult was practiced during the late Neolithic period, when numerous settlements on the coastal plain of the Tavoliere were abandoned in favor of migration towards the hilly areas, due to the change in climatic conditions; paleoenvironmental data in fact indicate a period of great drought for that period.

In 1973 Enrico Davanzo of the Cai of Trieste discovered, on the southwest side of the Camerone Quagliati, a passage towards the deepest part of the nearby Grotta di Occhiopinto and with subsequent surveys it was ascertained that the two areas, Scaloria and Occhiopinto, were part of a single underground structure, separated over time by the collapse of part of the vault.

The first systematic excavations were carried out only in the summer of 1978, as part of the research program on the "Neolithic of South-East Italy" coordinated and directed by Marija Gimbutas, at that time an archaeologist at the University of California and by Santo Tinè, archaeologist of the University of Genoa. Following these excavations, conducted in the Upper Chamber of the cave and near the entrance, it was possible to identify a necropolis, referable to the final moment of attendance of the cave, before the large landslide blocked the entrance. In the second excavation campaign of 1979, also conducted by Gimbutas, a layer referable to the Upper Paleolithic was found under the Neolithic layers with remains of a hearth, stone tools and animal bones; while, near the site of the collapse, when the cave became inaccessible, it was found that the area was also frequented for residential purposes referable to the fourth millennium. As Gimbutas wrote: “… The Scaloria Occhiopinto complex has provided the greatest amount of information on the Neolithic of all south-eastern Italy: its importance lies especially in the large chronological spaces, in the possibilities of studying the environment, populations, ceramics and religion … The Scaloria Cave is unique in Italy for its sacred place and for its burials …” (M. Gimbutas, 1981). The results of these excavations have never been published in full, only in 2016 were they the subject of a publication edited by Ernestine S. Elster, Eugenia Isetti, John Robb and Antonella Traverso, “The Archeology of Grotta Scaloria: ritual in Neolithic southeast Italy” – Los Angeles (CA) 2016, where the old and new excavation data are summarized.

The Upper Chamber of Scaloria is a large irregularly shaped chamber located immediately inside the entrance, with a maximum size of about 80 x 40 meters, with a maximum height of 2 meters in some points but generally much lower. Subsequent investigations, resumed since 2003 by the archaeologists Eugenia Isetti, Antonella Traverso and Ernestine Elster together with professor John Robb of the University of Cambridge, with subsequent samplings between 2007-2008 and 2013-2015, have ascertained a use of the Chamber Upper part of the cave both for housing and for the shelter of domestic animals (sheep, goats and pigs) and for the deposition of the dead, mainly attested between 5500 and 5200 BC even if in reality archaeological finds show that the cave was occupied from the end from the Pleistocene to the early part of the Copper Age.

Although only a small portion of the Upper Chamber has been excavated, the bone remains of a variable number between 22 and 33 individuals have been identified, of which about half are young, either men or women. Despite the high infant mortality attested, no particular pathologies were found that caused their death. Among the finds, 5 different funeral rites were identified:

- Single burials with grave goods, found during the Quagliati excavations in the 30s, with some intact vases in trichrome ceramic;

- Single burial without grave goods, found in the central part of the large room and attributable to an adult woman dated to 5322-5017 BC;

- Individual burial of a child of about 5-7 years old, datable to 5463-5221 BC found towards the back wall of the large room without a skull which would appear to have been removed after burial, probably for ritual use;

- Secondary deposition of a skull of an adult man placed in a small stone niche, but not dated to the Neolithic;

- Collective secondary depositions consisting of disconnected remains randomly scattered on the surface of the cave, some coming from complete skeletons and others the result of re-depositions, all dated to the Middle Neolithic, between 5500 and 5200 BC

The last burial case is the one that has aroused the greatest need for investigation. The human bones were scattered on the ground without a particular spatial distribution: they did not constitute grave goods intentionally placed or associated with particular remains, but the bones were broken before their final deposition and placed in no particular order.

Further investigations established that the bodies were buried elsewhere, subsequently removed, emptied of residual soft tissue and cleaned; as evidence there are small cut marks and superficial abrasion made with flint or obsidian tools (tools found in large numbers inside the cave), performed in particular on the cranial vault, jaws, clavicles and long bones. The bones were therefore broken, generally within the first year of death, when they were not yet dry and therefore elastic due to breaking and then placed as a secondary burial inside the cave, randomly mixed together with faunal remains, broken vases and utensils in stone. Tests with the isotope of strontium have ascertained that the bones came from villagers distributed within a radius of 15-20 km from the cave and only a few selected bones were deposited rather than the entire skeleton of the deceased.

What was the meaning of this ritual?

The care with which the bones were cleaned, selected and placed disorderly suggests that everything was part of a precise and highly significant ritual sequence, a practice not previously observed in Neolithic Italy; something similar, but referable to the following millennium, occurred in the Late Neolithic of Grapˇceva Cave, near the island of Hvar, but in reality that of Grotta Scaloria seems like a ritual in itself, especially if seen together with the cult of the waters of the lower part of the cave.

Although to date there is no evidence of the simultaneous existence of the two cults in the two chambers of the cave, that of the waters and that of the dead, the collected waters that filtered from the rocks could have had a purifying function in a ritual of veneration of the "stone bones ”, i.e. limestone sculptures formed by deposits of the earth. The stalactites and stalagmites form continuously in the cave and are one of the most important visual characteristics, very similar in appearance to the bones deposited there: cleaning the bones and placing them inside the same quarry could perhaps symbolize the union with the stone and a return to the origins in an ideal temporal cycle of incarnation.

Elvira Visciola – February 2022

REFERENCES

- Santo Tinè and Eugenia Isetti – Neolithic cult of water and recent excavations in the Scaloria Cave –2013;

- Andrea Ciampalini, Marco Firpo and Eugenia Isetti, Ivano Rellini, Antonella Traverso – “The cult of the sacred in the Grotta Scaloria complex (FG)” – in Journal of Ligurian Studies – LXXVII LXXIX (2011-2013) – pp. 289-293;

- Ernestine Elster, Eugenia Isetti and Antonella Traverso - "New study evidence from the site of Grotta Scaloria (FG)" - in Proceedings of the 28th National Conference on Prehistory - Protohistory - History of Daunia – 25-27 November 2007 – pp. 111-128;

- Carlo Lugliè - "Grotta Scaloria: the puzzle of a palimpsest" - in Journal of Prehistoric Sciences – Florence 2016 – pp. 295-300;

- Ernestine Elster, Eugenia Isetti, John Robb and Antonella Traverso – “Archeology of Grotta Scaloria: ritual in Neolithic Southeast Italy” – in Archaeological monument – 38 – The Cotsen Institute of Archeology Press – 2016;

- Ernestine Elster, Eugenia Isetti, Ivano Rellini, John Robb, Marianne Tafuri and Antonella Traverso – “See the world from Scaloria” – in Studies of Prehistory and Protohistory – Prehistory and Protohistory of Puglia – no. 4 - 2017 - p. 239-243;

- Eugenia Isetti, Antonella Traverso, Stefano Nicolini, Donatella Pian, Ivano Rellini, John Robb and Guido Rossi – “Scalaria cave. Surveys 2014 2015” – in Proceedings of the 36th National Conference on Prehistory - Protohistory - History of Daunia – 15-16 November 2015 – pp. 23-31;

- Marija Gimbutas – Grotta Scaloria, report on the 1980 research relating to the 1979 excavations – Municipal administration of Manfredonia – 1981;

- John Robb, Ernestine S. Elster, Eugenia Isetti, Christopher J. Knusel, Mary Anne Tafuri and Antonella Traverso – “Cleaning the dead: Neolithic ritual processing of human bone at Scaloria Cave, Italy” – in Antiquity – no. 89 - 2015 - p. 39-54;

- Mary Anne Tafuri, Paul D. Fullagar, Tamsin O'Connell, Maria Giovanna Belcastro, Paola Iacumin, Cecilia Conati Barbaro, Rocco Sanseverino and John Robb – “Life and death in Neolithic Southeastern Italy: the strontium isotopic evidence” – in International Journal of Osteoarchaeology – no. 26 - 2016 - p. 1045-1057;

- Ivano Rellini, Marco Firpo, Eugenia Isetti, Guido Rossi, John Robb, Donatella Pian and Antonella Traverso – “Micromorphological investigations at Scaloria Cave (Puglia, South-east Italy): new evidence of multifunctional use of the space during the Neolithic” – in Archaeological and Anthropoligical Sciences - 2020.