di Maria Laura Leone

For several ancient and traditional societies the female theme has been the main theme in art and crafts. It also occurred in the most ancient Daunia with the stele-statues, I have already dealt with this in a previous article written in English[1], of which the present is a partial review. The close analysis of the many female stelae led me to glimpse, in the scenes that cover them, arcane and ancient situations well known also in the ethnographic field. The text that follows deals with a part of these aspects and places the women of the stelae in a broad dimension, ennobled and connected to an organized cult in which healing and the relationship with the supernatural were practised, among other things. The pharmacological use of the opium poppy juices can be deduced from some scenes. The plant is, in fact, recognizable as a symbol of "women-medicine" who intervene on specific individuals.

The Dauni, the stelae and their women

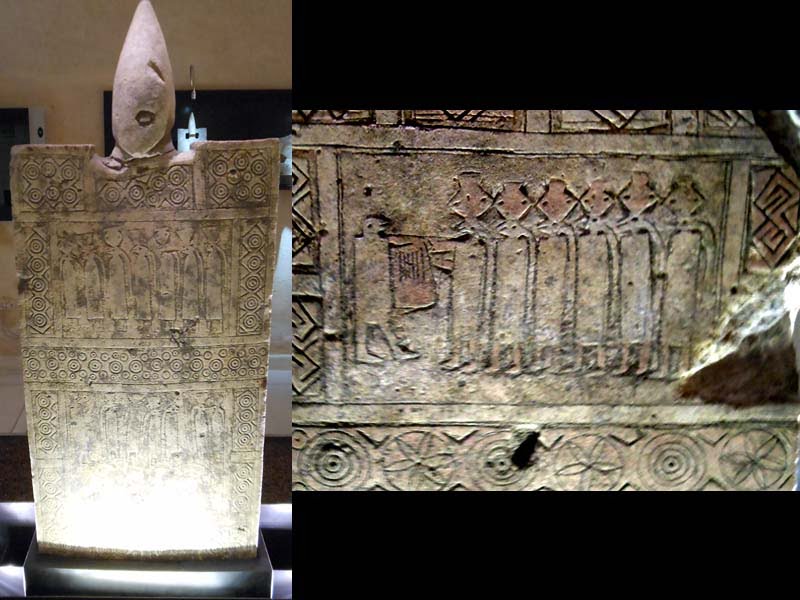

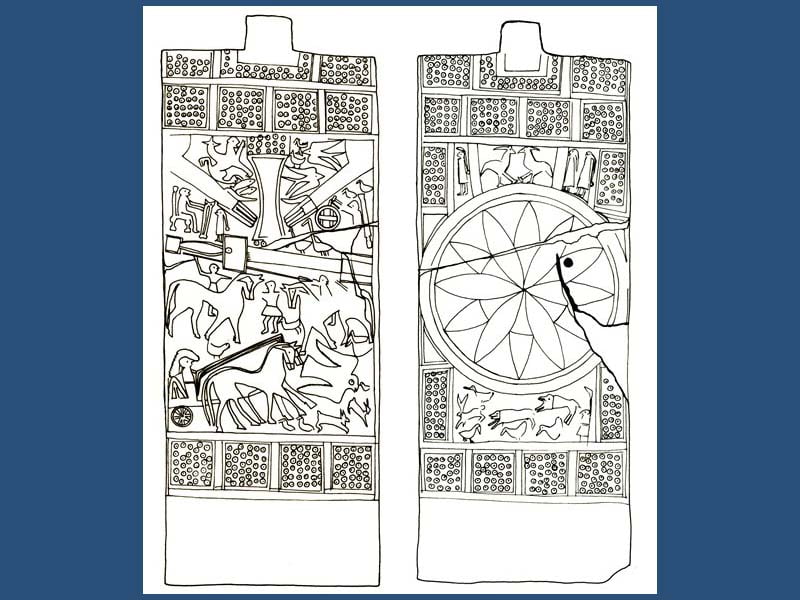

The Dauni civilization dates from the early Iron Age and the Romanization (IX-I century BC), a period during which about twenty inhabited centers arose in a wider territory than the current province of Foggia. Their anthropomorphic stelae are dated between the end of the XNUMXth and the beginning of the XNUMXth century, in the "second Iron Age", in a highly archaic and exquisitely indigenous phase, when artists, craftsmen and women, expressed themselves with great creativity. At the beginning of the sixth century BC the steles are found broken and reused, it is possible that the cult fell into a sort of iconoclasm. These slab-like works, carved in the local limestone and colored red, black and white, are the ideal finds for reconstructing different aspects of the world at the time. The narratives portray an entire social, religious, perhaps mythical structure, and in addition to the esoteric contents they report themes of daily life: a good hunt, a fruitful fishing, an armed duel. There is no shortage of scenes of possible love or marriage agreements, such as the situation in which a couple is portrayed in a probable embrace. We also recognize a hierarchy of roles: important figures seated on thrones or wearing high hats, bearers of vases, lyre players, charioteers, hunters and hoplites. On all the monuments women are well represented and the same number of female steles is significantly higher than that of male steles. By calculating the numerical difference between male steles with weapons and female steles without weapons, it appears that the latter had a higher incidence to be classified in their still unknown function[2].

Male stele and female stele portray two characters always similar to themselves, an important couple, perhaps a great warrior or a god with armor (Fig. 1), sword and shield, and a high priestess, perhaps also a goddess, dressed in cassock, adorned with necklaces and fibulae, pendant objects such as long triangular pendants from the belt in the shape of “VVVV” and large circular amulets (Fig. 2).

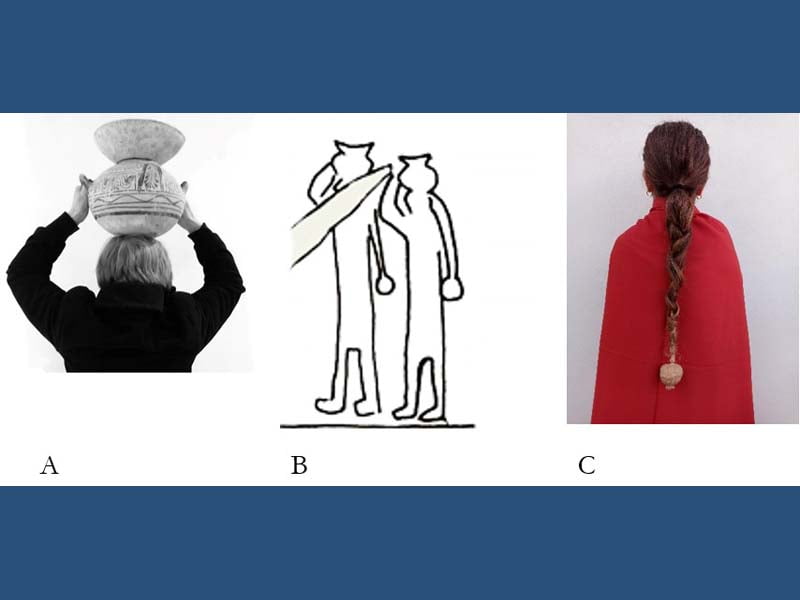

Among these amulets there are some quite similar to opium poppy capsules[3]. A plant that also decorates the braids of the women portrayed in the scenes (Fig. 3).

The clothing of both is rigorously decorated with geometric motifs and leaves free spaces in which there are descriptive scenes populated by animals and people. Some animals are surreal, others reflect the local lagoon fauna. Men and women are distinguished by some details: the women almost all have long hair, gathered in a braid, and wear a tunic that reaches below the knee; men have shorter dresses or even ones stopped at the waist by a belt. Almost all the finds, around 2000 pieces, are kept in the Museum of Manfredonia[4] and they come from the two ancient centers of Cupola-Beccarini and Salapia (also called Salpe), once overlooking the shores of a luxuriant lagoon now reduced to a few lakes and salt basins. The discoveries took place through the collection of surfaces and no stele was found in a secure relationship with its own tomb. They have no secure contemporary context and considering that some stelae are very small, only 25 cm high, it is conceivable that the intended use was not that of sepulchral stones, more likely propitiatory simulacra, votive offerings or acts of prayer intended for the couple : warrior and priestess. Several scenes refer to this and show the presence of a predominantly female priestly elite. It is clear, in fact, that the monuments have characters and stories associated with a large presence of women. However, those dedicated to warriors mainly depict men engaged in fighting and hunting, while women are mostly engaged in ritual activities.

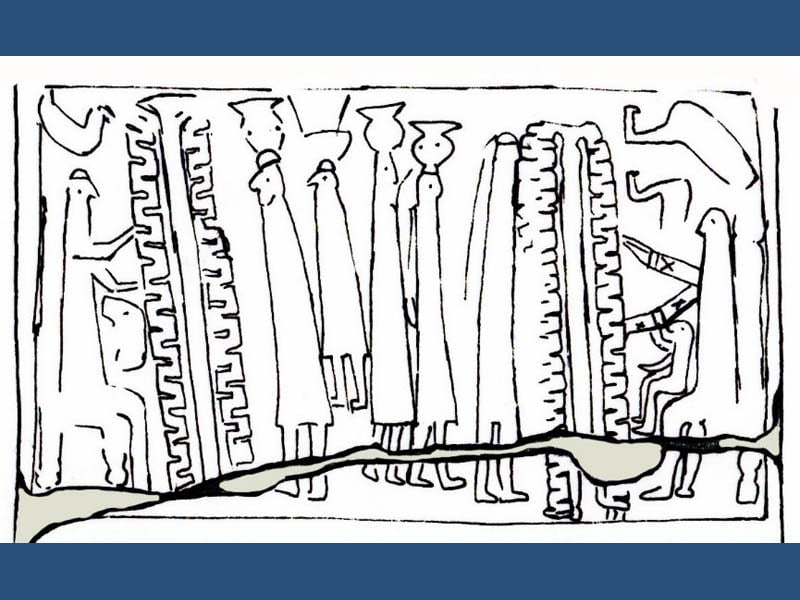

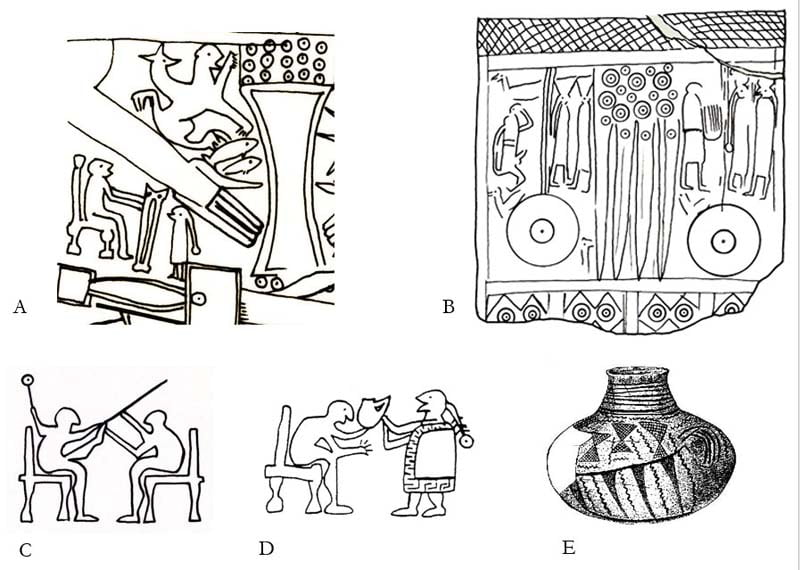

On the steles that refer to the priestess, women appear above all while they carry out courtly actions and attend to the affairs of men, converse with them, and often carry olla-pots with very wide lips balanced on their heads (Fig. 3 A and B), sometimes they parade in procession led by the sound of a lyre which is in the hands of a musician (Fig. 4).

In other scenes they talk to each other, practice therapeutic and possibly oracular sessions. Such mediation with the supernatural could be in a scene that repeats itself, where a woman of larger dimensions than the adept who is in front of her is on a throne and is weaving on a loom, her mouth is ajar and she addresses the adept who seems hang from his lips (Fig. 5 A).

B, central part of female stele with pubic triangles in VVVV, combined with small circles similar to liquid drops. Perhaps a metaphor for the female cycle

C and D, possible scenes of magic-therapeutic sessions

E, vase with reticulated hourglass figures and long triangles, similar to those of the stele, alternating with orioles of a liquid: Chiusazza (Syracuse), 3500-3000 BC (ph. M. Gimbutas, 1989)

Maybe conjure a prophecy, pronounce a magic formula, sing a hymn or narrate a myth. We won't know! But these are the situations in which women seem to act in the sacred sphere[5].

The segments in the shape of “VVVV” and the feminine gender

Armed stele and unarmed stele have many elements in common, the clothing is practically identical and the scenes both have repeating themes, but there are some attributes that clearly distinguish them, for example the weapons refer to a warrior but the attributes to form of "VVVV", connected to the basin of the stele with ornaments are, in my opinion, a clear feminine indicator[6]. This detail is of paramount importance for recognizing female gender stelae as they have an analogy with the single or multiple pubic triangles that appear on statuettes, stones, wall art and pottery. These triangles on the stelae are sublimated, elongated, and are sometimes combined with small circles comparable to drops, possible metaphors of the woman's monthly blood flow; the Chiusazza vase seems to be a good example (Fig. 5 B, E)[7]. The number of triangles, from three to six, can indicate the days of the cycle, the "monthly break" which various ethnic cultures interpret as the female moment of high sensory perception. We can only deduce what the Daunis meant by this symbology. It is possible that the reference to the monthly cycle is to be understood as a status of courtly virginity. At the same time, the large fibulae engraved on the chest of the monument would indicate the "firm" of the breast role. All of this can be superimposed on a woman who holds a curial status; therefore, the female stele would not portray a simple high-ranking deceased but a solemn figure and the women who are portrayed on her body would be her acolytes.

Maria Luisa Nava, as well as Silvio Ferri previously[8], attributes a funerary function to the Daunian steles. According to the author, they are semata sepulchrals of an elite class made up of warriors and notables and the female stelae, included in the group with ornaments, would be only those combed with a ponytail that descends over the shoulder. Based on this the author calculates[9] that out of a sample of 187 finds, well preserved and legible, 4 have pigtails, 23 are of uncertain attribution, 56 are of warriors and 103 are of notables. In total, 159 stelae are of deceased males, covering the role of notables and warriors, and just 4 stelae are of women, i.e. 2,12%. However, this percentage raises perplexity and questions. Why are the notables dressed, adorned and decorated, exactly like women with pigtails? What meaning would the triangles in the shape of "VVVV" have on the pelvis of notable males and what would be the meaning of the presence of so many women on all the steles? Nava's dissertations do not clarify these or other doubts, such as why from the first twenty-five years of the sixth century up to the third century BC. C. the steles are found broken and reused in tombs and homes. Who would ever have destroyed the tombstones of the ancestors, not respecting the sacred cult of the ancestors and the deceased? Instead, an iconoclasm resulting from the overthrow of a clerical class, now uncomfortable and inefficient, or the entry of new religious orders, would explain such a destruction.

According to Camilla Norman, an Australian scholar who embraces the theory of funerary destination, the "VVVV" motifs constitute a symbolic apron to refer to fertile women ready to marry, also due to the presence of weavers at the loom[10]. She too recognizes in the steles the reflection of a society in which women have a significant presence[11] but it doesn't explain why so many deceased women and few deceased warriors. Once again it doesn't add up. According to a personal analysis, the "VVVV" signs, possible symbolic "aprons" of fertility, as reported by Norman, are to be declined in a cultic key and it is from this point of view that weaving should also be understood; such as the creation of a fabric to be destined for the high priestess and/or for women dressed like her. In Athens, in a period close to the stelae of the Dauni, the Ergastinai virgins also wove the peplos for the virgin goddess Athena Partenos. Therefore, weaving should be understood as a liturgical act in which bird-spirits participated, acolytes carrying ollas full of precious content, and weavers who, similar to "enthroned majesty", sang or evoked myths and magical formulas. In this liturgy the period of the cycle of a sacred virgin must be inserted, connected to the importance of the poppy plant, very precious to cure and soothe pain. Thus the stele reveals itself as the simulacrum of a hierobotanic cult and its poppies, hooked to the belt and turned downwards (Fig. 2), would represent a ritual sowing which evidently took place through a virgin with the sky.

Vase ceramics

From the foregoing it emerges that in the most archaic Daunia esotericism and medicine required the participation of women, perhaps the same protagonists painted on a rare repertoire of figurative vases[12]. They are not contemporary vases to the steles, they range from the XNUMXth to the XNUMXrd century BC, but they have themes comparable to them and perhaps they are a continuation of them. Also on these appears a sacred couple portrayed while exchanging an important but yet to be identified plant[13]. Usually it is the man who receives it, but on the vase of the Tardivat Collection in Geneva both eat it and the man squeezes a lyre from which a poppy capsule is hung, mistakenly interpreted as the plectrum of his musical instrument (Fig. 6 A,B)[14].

B – Detail of a similar scene in which the couple eats the plant. The woman has a stick and the man holds a lyre from which a poppy sprouts. The two vegetables are reproduced below, as a symbolic decoration; Geneva, Tardivat Collection (ph. Chamay, 1994)

On the same vase there are decorative capsules on the surface, similar to those present on jug no. 63 and on the filter pot n. 35. Excluding this small repertoire, Daunia ceramics have a geometric decoration. The decorations are colored red and brown and the vascular shapes are peculiar; such as the duck-shaped askoi, the ladles and filter-vases rich in suggestive protomes, enriched by hands, feet, zoomorphic faces, birds, wolf-dogs, bucranium handles, or anthropomorphic figures with open arms and rings instead of hands[15]. The protome of a woman with fibulae, jewels, long braids and a polos headdress often appears on the filter-vases, already defined as a priestess[16], or even a shaman, connected to the effectiveness of the medicinal infusion or magical preparation of the vessel itself. These are symbolic additions that reflect strong magical and superstitious thinking.

The ancient sources

Between the fourth and third centuries. to. C. some sources mention Daune women[17]. Timaeus of Taormina describes them in dark clothes, girded in wide bands, with high shoes, their faces colored in fiery red and a stick in their hands. To the Greeks they remind the Erinyes. It is clear that the author describes uncommon women, intimidating and perhaps not accessible women. But the broadest information comes from Licofrone in the work Alessandra and from Scholia themselves. Lycophron describes in detail what Daunian girls who do not want to get married do: they take refuge in the temple of the virgin Cassandra, the prophetess priestess whose cult would have been introduced by Diomene in Salapia, and they embrace her statue. They dress in black like the Erinyes, they dye their faces with the juice of evil herbs and they carry a stick. In the temple located near the swamp of Salpe (Salapia) – the indication of Salpe is from the Byzantine scholiast – Cassandra will welcome them and guarantee their virginity[18]. It is surprising how this description corresponds to a priesthood of virgins and how much the staff recalls the giant poppy. In fact, the plant can reach one and a half meters in height, it is similar to a mace or scepter when held in the hands and can be harmful if one exaggerates with the doses of its juice: opium. In addition to these hints of folklore, the Lycophron passage also shows us an uncommon female freedom for the time, inherent in the choice not to marry unwanted men. A choice that can be interpreted, like a "religious" devotion to a deified prophetess.

Artists and craftsmen

The Daunian stelae seem to testify to this freedom together with a centrality of gender, evidently, which survived the impact of Indo-European cultures[19]. It is possible that women in ancient Daunia enjoyed some prestige like the contemporary Etruscans who lived in a sort of "pocket of resistance to patriarchy", an oasis of the feminine reported in some sources. It seems that in Etruria the ladies were not subjected to the guardianship of their father or husband as, instead, happened in Greece and Rome, they participated in banquets and public events, they entertained themselves to talk with the guests, they made up and dressed without constraints[20]. From the steles we deduce that the Daunes were also active in textile craftsmanship but it is not excluded that they also made vases or that they had a role in the conception-design of the anthropomorphic steles on which they are protagonists. These are deductions, but it is widely testified that in some tribal populations the transmission of magical-symbolic baggage is an exclusive female domain. This is confirmed by the studies of the researcher Makilam, the North African scholar who gave a voice to the Kabile Berber women, skilled craftsmen who decorate carpets, ceramics, huts and tattoos[21].

Footnotes

[1] Leo 2020 ab.

[2] The calculation results from the finds in the catalogue: Nava 1980a.

[3] Leone 1990, 1992, 1995, 1996a, 1996c, 2000a, 2000b, 2002a, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2007, 2020a, 2020b.

[4] Of this set, 1210 well photographed and documented specimens are collected in a corpus: Nava 1980a.

[5] For a dissertation on the female relationship with the sphere of the sacred, in the Orientalizing era, see: Von Else, 2008.

[6] Leo 1996 p. 57.

[7] It is an Eneolithic vase decorated with pendulous triangles alternating with tremulus or oriole motifs: Gimbutas 2008, p. 243, fig. 379.

[8] An exhaustive collection of Silvio Ferri's studies is in Nava 1988.

[9] Nava 2014, p. 159.

[10] Norman 2018.

[11] Norman 2011. The analogy between some scenes on the steles and the procession of the Panathenaics is interesting, with the animals for sacrifices, the bearers of offerings, the musicians and the canephors: the bearers of baskets full of gifts, who wore the peplos and vessels for libations.

[12] DeJuliis 2009.

[13] Leone 1995, 1996abc, 2000, 2007.

[14] Chamay 1994, p. 256-257; Chamay and Coutois 2003, pp. 128-129; DeJuliis 2009, p. 112.

[15] Mayer 1914; DeJuliis 1977; Yntema 1985.

[16] Maes 1975.

[17] A complete and reasoned collection of the sources that speak of the Dauni is in Notarangelo 2008.

[18] Lycophron Alexandra, 126/141; Notarangelo 2008, p. 38/44.

[19] Gimbutas 1989; Percovich 2007, 2009.

[20] Rallo 1989.

[21] Makilan 2007. http://convegni.associazionelaima.it/blog/estratto-da-simboli-e-magia-nelle-arti-delle-donne-kabyle-di-makilam/ (accessed on 07/01/2021).

Maria Laura Leone – December 2021

REFERENCES

- AAVV – Princes, Emperors, Bishops. Two thousand years of history in Canosa – Marsilio – Venice 1992;

- Emmanuel Anati – “Origin and historical-religious significance of the stele-statues” – Bulletin of the Camuno Center for Prehistoric Studies n. 16 – 1977 – p. 46-56;

- Emmanuel Anati – “The sates of the research in rock art. The Alpine menhir-statues and the Indo-European problem” – Bulletin of the Camuno Center for Prehistoric Studies – no. 25-26 – 1990 – pp. 13-44;

- Angelo Bottini – Warrior princes of Daunia of the VII century. The Princely Tombs of Lavello – De Donato – Bari 1982;

- Ettore Maria De Juliis – The geometric pottery of Daunia – Sansoni – Florence 1977;

- Ettore Maria De Juliis – The Japiges. History and civilization of pre-Roman Puglia – Longanesi & Co – Milan 1988a;

- Ettore Maria De Juliis – “The origin of the Iapige people and the civilization of the Dauni” – in: AA.VV. – Italy omnium terrarum alumnum – Garzanti-Scheiwiller – Milano1988b – pp. 593-650;

- Ettore Maria De Juliis - "Balance of current studies and knowledge on the Daunian civilization" - in Vetera christianorum – no. 2 – 1988c – pp. 661-676;

- Ettore Maria De Juliis – “The daunia olla with funnel-shaped lip. Origin, form and development” – in Classical Archeology - 1993 - 1991 - pp. 893-913;

- Ettore Maria De Juliis – “Manfredonia. Masseria Cupola (Foggia) – Excavations in the necropolis” – News of the excavations – VIII – vol. XXXI – 1997a – pp. 343-388;

- Ettore Maria De Juliis – The figurative representation in Daunia – EdiPuglia – Bari 2009;

- Jacques Chamay – L'art des peuples italiques: 3000 à 300 avant J.-C. – Geneva 1994;

- Jacques Chamay and Chantal Courtois – The Art Premier of Iapyges. Céramique Antique d'Italie Méridionale – Geneva/Naples 2002;

- Marija Gimbutas – The language of goddess – Thames and Hudson – London 1989;

- Maria Laura Leone – “Rare example of decoration in the geometric Daunio” – Archeoclub newsletter of San Ferdinando di Puglia (Foggia) – 1990 – p. 1-2;

- Maria Laura Leone - "From the fragment of Salapia to the Daunian stele" - in Archeoclub newsletter of San Ferdinando di Puglia (Foggia) – 1992 – p. 1;

- Maria Laura Leone - "New acquisitions on Daunian geometric ceramics" - in Archeoclub newsletter of San Ferdinando di Puglia (Foggia) – 1994 – p. 3;

- Maria Laura Leone – “Opium. “Papaver Somniferum”, the plant sacred to the Dauni of the steles” – in Bulletin of the Camuno Center for Prehistoric Studies – no. 28 – 1995 – pp. 57-68 - (consulted on 07/01/2021);

- Maria Laura Leone – “Still on the “Stele Daunie”” – in The Captaincy – Review of Life and Studies of the Province of Foggia 1996a – pp. 32-33 – new series no. 3-4 – pp. 141-170 – (consulted on 07/01/2021);

- Maria Laura Leone - "Archaeology and plants of the gods" - in Bulletin of the Camuno Center for Prehistoric Studies – vol. 29 - 1996b - pp. 7-8;

- Maria Laura Leone - "New interpretative proposals on the Daunian stele" - in Bulletin of the Camuno Center for Prehistoric Studies – vol. 29 – 1996c – pp. 57-64;

- Maria Laura Leone – “The ideology of statues-menhirs and statues-stelae in Puglia and the conceptuality of the phallic-anthropomorphic symbol” – in Gods in stone. Notebooks of the Lombard Archaeological Association – 2000a – pp. 119-145 - (consulted on 07/01/2021);

- Maria Laura Leone – “Pomegranate or Papaver somniferum?” – in Archeoclub newsletter of San Ferdinando di Puglia – (Foggia) 2000b – p. 2;

- Maria Laura Leone – “Ideographic writing on the Daunian stele. The stele Samson” – in Archeoclub newsletter of San Ferdinando di Puglia – (Foggia) 2002 – p. 1;

- Maria Laura Leone - "Sacred opiate botany in Daunia (Southern Italy) between VII-VI BC" - in Eleusis, International Review. Plants and Psychoactive Compounds (Civic Museum of Rovereto) – 2002-2003 – 2003 – pp. 71-82;

- Maria Laura Leone Anthropomorphic stele of Puglia "Castelluccio dei Sauri and Bovino in the ideology of the statue-stele and statue-menhir" – 2004 – (accessed November 24, 2020);

- Maria Laura Leone – “"Comics" sequence in the narrative of the Daunian stelae” – in Archeoclub newsletter of San Ferdinando di Puglia (Foggia) – 2005 – p. 2 – (consulted on 07/01/2021);

- Maria Laura Leone – “Stele Daunia. Funerary semata or votive statues?” – in Hypogea, notebooks of the “S. Bracket” – December 2007 – n.1 – pp. 83-92;

- Maria Laura Leone – “The woman in ancient Daunia (Apulia, Italy). Considerations inferred from steles, sources and ceramics” – in EXPRESSION – no. 27 - Quaterly e-journal of "Atelier" in cooperation with uispp-cisnep. (International Scientific Commission on the Intellectual and Spiritual Expressions of non-literate Peoples) – March 2020a – pp. 56-66;

- Maria Laura Leone – “Artisans, curators, women of enchantment in the logos “Stele Daunie”” – in African Archaeology – Occasional essays by the African Archeology Study Center – n. 25-26 – Milan 2020b – pp. 65-77;

- K. Kilian - "Evidence of religious life in the early Iron Age in southern Italy" - in Reports of the Academy of Archeology of Naples – no. 41 - 1996 - p. 91-104;

- Morena Luciani – Shaman women – Venice – Rome 2012;

- Marina Mazzei – The ancient Daunia in the feminine – Grenzi – Foggia 2020;

- K. MAES – “The small clay plastic of Daunia” – in Bulletin of the Institut Historique Belge de Rome – no. 44 - 1975 - p. 353-378;

- Maximilian Mayer – Apulien, vor und whärend der Helleniseirung – Leipizing – Berlin 1964;

- Makilam –Symbols and Magic in the Arts of Kabyle Women – Peter Lang – New York 2007;

- Marina Mazzei – The Daunians. Archeology from the XNUMXth to the XNUMXth century BC – Grenzi – Foggia 2010;

- Maria Luisa Nava - "New anthropomorphic steles from Castelluccio dei Sauri (Foggia)" - in Annals Civic Museum of La Spezia – vol. 2 - 1979/80 - pp. 115-143;

- Maria Luisa Nava – “Stele Daunie, the work of Silvio Ferri” – in Great Greece - XIV nn.7-8 - 1979 - pp. 8-11;

- Maria Luisa Nava – Stele Daunia – Sansoni – Florence 1980a;

- Maria Luisa Nava – “Daunian stele in the Gallarate Museum” – in Gallaratese Review of History and Art – XXXV no. 122 – 1980b – pp. 25-32;

- Maria Luisa Nava - "Stele Daunie: problems of sub-Garganic protohistory" - in Proceedings of the Conference Ancient civilizations and cultures between Gargano and Tavoliere – S. Marco in Lamis 1979 – 1980c – pp. 83-89;

- Maria Luisa Nava – The stele of Daunia: from the discovery of Silvio Ferri to the most recent studies – Electa – Milan 1988;

- Maria Luisa Nava – “New data on sculpture in Daunia from the Metal Age to the Archaic Age. The role of the scenes in the historiated stele of the Tavoliere” – in Chiara Lampert and Felice Pastore (edited by) – Myths and peoples of the ancient Mediterranean. Written in honor of Gabriella d'Henry - Arci Postiglione - Salerno 2014 - pp. 151-166;

- Camilla Norman – “Warriors and Weavers: sex and gender in Daunian Stelai” – in Edward Herring and Kathryn Lomas (eds) – Gender Identities in Italy in the First Millennium BC – BAR International Series 1983 – British Archaeological Reports Oxford Ltd 2009 – pp. 1-7;

- Camilla Norman – “The Tribal Tatooing of Daunian Women” – in European Journal of Archaeology – no. 14 (1-2) – 2011a – pp. 133-157;

- Camilla Norman – “Weaving, Gift and Wedding. A Local Identity for the Daunian Stelae” – In Margarita Gleba and Helle W. Horsnaes – Communicating Identity in Italian Iron Age – Oxbow Books Ltd 2011b – pp. 33-49;

- Camilla Norman – “Illyrian Vestiges in Daunian Costume: tattoos, strings aprons and a helmet” – in Gianfranco De Benedittis – Comparison of Middle Adriatic realities: contacts and exchanges between the two shores – Lightning 2018 – pp. 55-71;

- Maria Leonarda Notarangelo – Ethnography and myths of Ancient Daunia. Repertoire and commentary on literary sources (late XNUMXth century BC - XNUMXth century AD) – Grenzi – Foggia 2008;

- Luciana Percovich – Dark shining mothers – The roots of the sacred and of religions – Venice – Rome 2007;

- Luciana Percovich – She who gives life, she who gives shape – The owls of Venexia – Rome 2009;

- Antonia Rallo (edited by) – Women in Etruria – The Herm of Bretschneider – Rome 1989;

- Filli Rossi – Daunia geometric ceramic in the Ceci Macrini Collection – Daedalus – Bari 1979;

- Lush Marguerite – Parthenogenesis. The cult of divine birth in ancient Greece – Psyche 2 – 2012;

- George Samorini – Hallucinogens in the myth. Stories about the origin of psychoactive plants – Nautilus – Turin 1995;

- George Samorini – Italian origins of opium? Herbal shop Tomorrow n. 396 – 2016 – p. 70-76;

- George Samorini – Hallucinogenic mushrooms. Ethnomycological Studies – Telesterion – Bologna 2002;

- Matthias Seefelder – Opium. Social history of a drug from the Egyptians to today – Garzanti – Milan 1990;

- Richard Evans Shultes, Albert Hofmann and Christian Ratsch – Plants of the gods. Their sacred, healing and hallucinogenic powers – Venice – Rome 2021;

- Douwe Geert Yntema – “Messapian painted pottery – Analysis and Provisional Classification” – in Archaeological studies at the Nederlands Institute in Rome – Rome 1974;

- Douwe Geert Yntema – The matt-painted pottery of southern Italy – Utrecht 1985;

- Patricia Von Eles – “The Hours of the Sacred. The feminine and women, subjects and interpreters of the divine?” – in Women's hours and days. From everyday life to sacredness between the eighth and seventh centuries BC – Exhibition catalog – Verucchio 2008 – pp. 149-156.