di Elvira Visciola

The Grotta di Fumane represents one of the most important archaeological archives of the Middle and Upper Paleolithic in Europe. Inhabited first by Homo Neanderthalensis and subsequently by Homo Sapiens, in a period that goes from about 90 to 25 thousand years ago, it offers an important testimony of the dynamics that led to those biological and cultural changes in human evolution, up to the affirmation of our species occurred around 40.000 years ago.

The cave is a karst cavity located about 6 km north of the town of Fumane, in the Valpolicella area, near the Lessini mountains, in the province of Verona; it is located about 350 meters above sea level and is characterized by a large atrium with three galleries, which have not yet been fully explored. The exposure of the cavity to the south together with the presence near a stream and the size of the atrium (about 100 m1600) favored the development of the human settlement; the strategic position of the cave, between the plain below and the peaks up to XNUMX meters high, was the ideal condition for hunting in different environments (ibex, chamois, deer, roe deer, etc.), while the rock formations rich in flint they favored the procurement of materials for various uses.

Until 1960 the cave was not yet known as the entrance was covered by landslide debris mixed with thick vegetation; however already in the 1962th century a report by the engineer Stefano de Stefani reported a landslide of dolomitic rocks mixed with archaeological material near the road to Molina, the one that passes in front of the cave. The latter was definitively discovered in 1964 by the archaeologist Giovanni Solinas, to whom we still owe the name of Riparo Solinas, but the first exploration by a team of scholars from the Natural History Museum of Verona only took place in 1982 , assisted by Angelo Pasa and Franco Mezzena, works prematurely interrupted due to the sudden death of Prof. Pasa. After this first research, a long period of abandonment followed, with the repeated clandestine looting of the surface deposits; only in XNUMX did the first effective investigation campaign take place, entrusted to the coordination of Alberto Broglio and Marco Peresani of the University of Ferrara and Mauro Cremaschi of the University of Milan, excavations which are still in progress, carried out for two or three months every year.

The cave has a length of about 22 meters and a depth, measured at its furthest point, of about 10 meters; the various accessible areas have yielded stratigraphic sections of about 12 meters down to the bottom of the rock and are being studied by specialist teams from Italian, English, French and German research centres. Overall, four macro stratigraphic units were distinguished, from bottom to top, defined on the basis of the characteristics of the rocks and the content of anthropic finds, such as to also provide precise information on climatic and environmental changes that have occurred over time.

The first layer refers to the Mousterian period (Middle Palaeolithic), so called from the classic Shelter of Le Moustier, in the Dordogne, which is approximately between 80 and 45 thousand years ago; investigated only minimally, it reflects the existence of a wooded landscape, attributable to the initial phase of the last glaciation (Wurm Glacier); it is superimposed on a layer of breccias and dust carried by the wind, expression of a much colder climate, characterized by the expansion of Alpine glaciers on high ground and by a steppe landscape in the Pre-Alps and in the Po Valley. In this period the area was frequented by groups of Neanderthals adapted to cold environments, but with visits to the cave of short duration and repeated over time probably because during this period the Neanderthal groups were less numerous and went to these areas only for short trips of hunting.

Many combustion structures similar to hearths with similar characteristics have been found: a thin layer of reddened sand at the base, covered by about 1 cm. of dark brown coals with the presence of ashes in the center or on the side of the hearth. In some of these hearths, subsequent reuse has been found, after some time, as a hearth or as a landfill for burnt materials removed from neighboring hearths; a hearth was found surrounded by stones to probably protect it from the winds coming from outside the cave. Together with the coals, bone remains of animals were found, such as cervids, wild boars, moose, primeval ox, goats and bison, as well as various stone tools used to butcher prey and to work their skin or to transform other stones into scrapers and points .

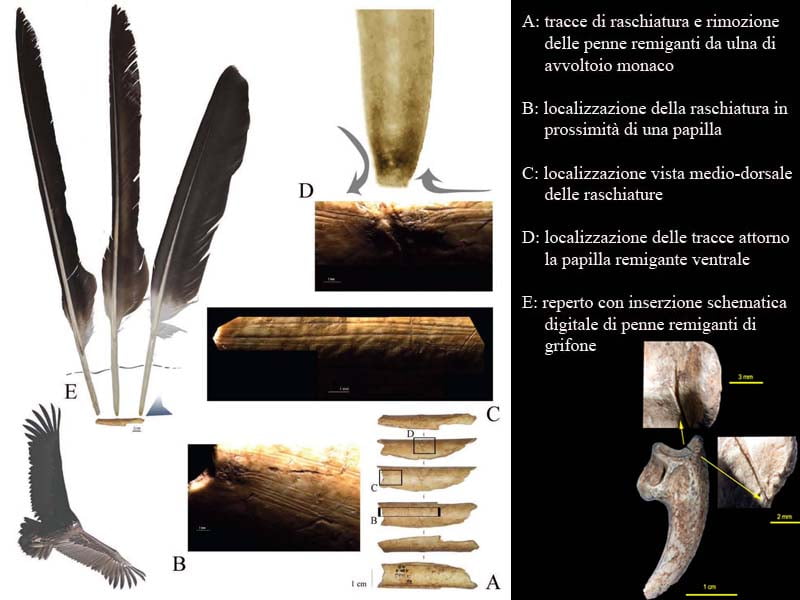

A very interesting discovery of this layer was the discovery of bird wing bones (a bearded vulture, a red-footed falcon, a wood pigeon, an alpine chough and a monk vulture) cut and scraped certainly not for food use, but in such a way to cause the detachment and recovery of the flight feathers, probably used for personal decoration to adorn clothes, objects or homes, as can be found in the feather art of current and sub-current primitive populations. In addition to the wing bones, a nail phalanx was recovered with some striae that suggest the precise intention to recover the claw from the raptor. It should be noted that these practices were only attested from 15 years ago until the Middle Ages and therefore these discoveries allow us to backdate the expressive capabilities of the Neanderthal species by tens of thousands of years, with forms of symbolic behavior and the use of ornaments as an expression of an abstract language. In confirmation of this there is also the discovery of a fossil shell, the Aspa marginata, with evident streaks of a cord for suspension and the application on the surface of traces of finely ground pure hematite. The presence of the jewel testifies to an intentional collection of the object, which took place at a minimum of 110 km away from the place where it was found (probably taken on the Ligurian or Adriatic coast) while the ocher on the shell is presumably hematite taken in one of the quarries located between 5 and 20 km away from the cave.

For almost the entire XNUMXth century it was thought that the Sapiens population was the first to express symbolic behavior, hence the appellation of "modern men", but the findings of the Fumane cave provide new light on the cognitive abilities of the Neanderthals who were therefore own and not derived from contact with the Sapiens.

The second layer refers to the Uluzzian period, so called from the caves of the Bay of Uluzzo in Salento, which represents the level of attendance of the last Neanderthals and the first diffusion of modern men, therefore to all intents and purposes it is a transition level between 45 and 40 thousand years ago; it is characterized by the alternation of colder and arid phases with less cold and more humid phases, during which the glaciers retreated. At Fumane the stratum is characterized by a change in the tools, due to the appearance of new stone or bone tools made with technical innovations both in the way of production and in use. As far as the hearths and other inhabited structures are concerned, as well as the traces of the food economy, they are substantially similar to the Mousterian levels.

The third layer refers to the Aurignacian period, between 40 and 32 thousand years ago, so named after the rock shelter of Aurignac, a small town in the Low Pyrenees in France; it is the most investigated stratum, anciently frequented between the end of spring and autumn, occasionally during the winter, testifying to the fact that the ancient inhabitants practiced a seasonal migration system, probably linked to hunting times and climatic conditions ( with cold climates the populations moved to warmer places); this period is characterized by the definitive disappearance of the Neanderthals and the diffusion of the Sapiens which took place around 41 thousand years ago. As for the Neanderthals, the Sapiens also fed on hunting products and the cave served as the main camp organized into sectors for specific activities, with areas for the various phases of flint processing, for the treatment of hides, for lighting fires, for the production of pictorial expressions in red ocher and areas where waste accumulated.

The inhabited area extended for about a hundred square metres, especially in the area of the atrium, while the internal areas of the cave have not yet been explored; the walking surface was leveled to create a horizontal plane on which several hearths were found; the larger one, with a diameter of about 1 meter and a depth of 6 cm., is located at the entrance to the cave, surrounded by large stone slabs and four post holes, as if a cover placed against the entrance arch served as a shelter.

But the most important archaeological evidence of the time are the ornamental objects made from marine shells and deer teeth, as well as evidence of the use of red ocher in decorated objects and paintings which constitute a rich documentation of the spirituality of these peoples. Nearly 1000 sea shells have been found, probably collected along the Tyrrhenian or Adriatic coasts and belonging to over 50 different species, mostly whole and often perforated, some with their original colouring, while traces of red ocher can be found on others; they were found together with four deer incisors, both of which were drilled to thread a rope and then make jewelry to wear. The species found testify that they took care to carefully choose the most beautiful and smallest specimens. About sixty shells still intact were found in a corner of the cave, perhaps accumulated in that place to proceed with subsequent processing. Other archaeological evidence testifies to the processing of bone and horn for the production of tools and zagaglie. The use of red ochre, common to many Aurignacian sites in Europe, is present in the Fumane site in the form of lumps, in fact the earthy hematite was mixed with an organic glue, often beeswax which also worked as a water repellent. Red ocher also served as an anti-fermentant in the treatment of animal skins.

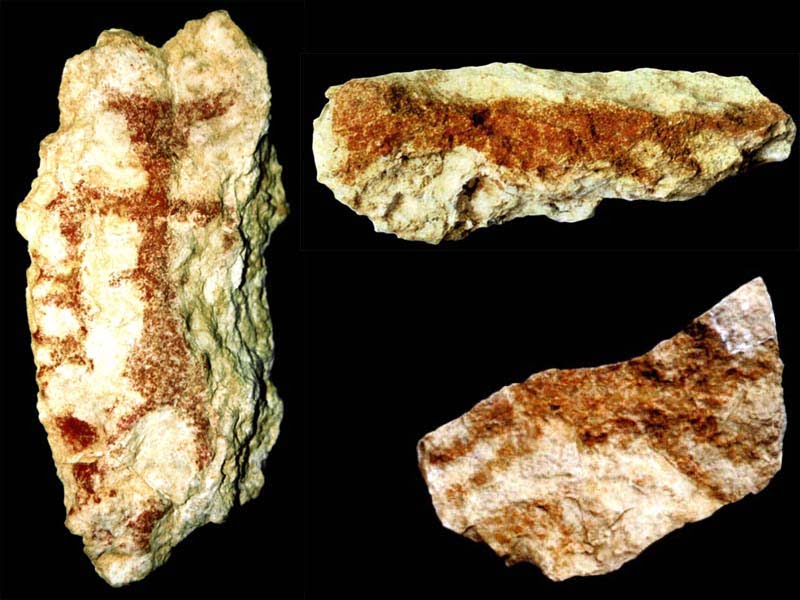

In addition to the shells, the exceptional find consists of 6 fragments of rock, with red ocher paint, which detached from the walls or vault of the cave, therefore found on the Aurignacian soil and are today among the oldest pictorial expressions (see “Painted stones from Grotta Fumane"). Many wall decorations of caves in the Franco-Cantabrian area can be attributed to the Aurignacian period, the latter often used as a cave-sanctuary rather than as a dwelling, as is evident in Fumane. The fragments of painted rock detached during the Aurignacian occupation and remained deposited on the walking surface of the time. Two are the best known, one with the outline of an animal, a mustelid or a felid and the other painted with the outline of a shamanic figure seen frontally, with a headdress or mask with two horns holding a votive object in its hand. The other recovered fragments, on the other hand, do not allow for a precise interpretation as they are too fragmentary representations but, overall, the Fumane finds are among the oldest in Europe.

The last layer refers to the Gravettian, datable to around 30 years ago, when the cave was abandoned, with some sporadic presences; in particular, a single Gravettian back point was found, a typical jet weapon of the time, which is traced back to about 25 thousand years ago.

It is assumed that the cave collapsed around 20 years ago and remained intact up to the present day of its rediscovery. In the inner part of the main gallery there is an as yet unstudied concentration of large bones, formed after the site was abandoned, when the cave became a den for hyenas.

Elvira Visciola – April 2021

REFERENCES

- Stefano Bertola, Alberto Broglio, Emanuela Cristiani, Mirco De Stefani, Fabio Gurioli, Fabio Negrino, Matteo Romandini and Marian Vanhaeren – “The diffusion of the early Aurignacian south of the Alpine arc” – in Alpine prehistory - 47 - Trento 2013;

- Andrea Cusinato and Michele Bassetti – “Human population and paleoenvironment between the culmination of the last glaciation and the beginning of the Holocene in the Trentino area and neighboring areas” – in Trentino Studies of Natural Sciences – Acta Geologica – Trento 2007;

- Alberto Broglio, Mirco De Stefani and Fabio Gurioli – “Aurignacian paintings in the Fumane cave” – in Proceedings of the Veneto Institute of Sciences, Letters and Arts – Volume CLXII – 2003;

- Marco Peresani, Davide Basile, Laura Centi, Davide Delpiano, Rossella Duches, Camille Jequier, Nicola Nannini, Marija Obradovic, Andrea Picin and Matteo Romandini – “Fumane cave. Results of the 2012 excavation and research campaign” – in News of the Archeology of the Veneto –2012;

- Alberto Broglio and Mauro Cremaschi – “New research at the Shelter of Fumane” – in La Lessina, yesterday today tomorrow – Cultural notebook 1989;

- Marco Peresani, Davide Delpiano, Rossella Duches, Jacopo Gennai, Diana Marcazzan, Nicola Nannini, Matteo Romandini, Alessandro Aleo and Arianna Cocilova – “The Mousterian of units A10 and A11 in Grotta Fumane (VR). Results of the 2014 and 2016 excavation campaigns” – in The Journal of Fasti Online – Rome 2017;

- Isabella Caricola, Andrea Zupancich, Giuseppina Mutri, Daniele Moscone, Marco Peresani, Emanuela Cristiani – “A functional and spatial approach to the function of Paleolithic polished stone tools. Preliminary results from Fumane Cave (Italy)” – in Annual meetings of Prehistory and Protohistory - 4 - 2018 - pp. 86-88;

- Marco Peresani - "Cave of Fumane (Fumane in Valpolicella, VR)" - in Annals of the University of Ferrara – Vol. 15 – 2019;

- Marco Peresani – The Way We Were – A Journey through Paleolithic Italy – The Mill 2020;

- Piero Leonardi – “Mousterian scraper from Riparo Solinas in Fumane (Verona) with incisions on the cortex” – in Proceedings of the Rovetana degli Agiati Academy – no. 230 - 1981;

- Alberto Broglio – “Discontinuity between the Mediterranean Mousterian and Protoaurignacian in the Fumane cave (Monti Lessini, Venetian Prealps)” – in Veleia - 12 - 1995;

- Alberto Broglio and Mauro Cremaschi – Excavations conducted between 1988 and 1991 – Veneto Region Department of Culture 1992;

- Marcello Bolognesi, Marija Obradovic, Nasser Abu-Zeid, Marco Peresani, Alessio Furini, Paolo Russo and Giovanni Santarato – “Integration of laserscan and photogrammetric surveys with geophysical methodologies applied to a Pleistocene cavity with archaeological stratification” – in Proceedings of the Rovetana degli Agiati Academy – no. 265 - 2015;

- Alberto Broglio, Mauro Cremaschi, Marco Peresani, S. Bertola, M. Colombini, Mirco De Stefani, G. Di Anastasio, G. Giachi, Fabio Gurioli, D. Marini, D. Masetti, F. Modugno, A. Padovani, P Pallecchi, O. Passerella, E. Ribechini, L. Tomesani, F. Velluti and R. Zorzin - "The painted stones of the Aurignacian" - in Alberto Broglio and Giampaolo Dalmeri (edited by) - "Paleolithic paintings in the Venetian Pre-Alps : Grotta di Fumane and Riparo Dalmeri” – Proceedings of the Symposium - Memories of the Civic Museum of Natural History of Verona – 2 series – Human Science Section 9 – Alpine Prehistory n. Special – 2005;

- Marco Peresani, Stefania Dallatorre, Paola Astuti, Maurizio Dal Colle, Sara Ziggiotti and Carlo Peretto – “Symbolic or utilitarian? Juggling interpretations of Neanderthal Behavior: new inferences from the study of engraved stone surfaces” – in Journal of Anthropological Sciences – vol. 92 - 2014.