Adapted from Marija Gimbutas – THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GODDESS - Vol. 1 – Alternative Press / New Balances – June 2012 – (pag. 176 – 185-186)

The first inhabitants of the Adriatic coasts and islands lived by hunting small animals until about 7000 BC, when a transition to a shellfish-harvesting economy was made. In the Adriatic islands and in the coastal regions of southern Italy, Greece, Albania and Yugoslavia, the improvement of navigation techniques enhances communication exchanges.

Three open-air settlements found in Sidari on the northwestern tip of the island of Corfu (Western Greece) are excellent examples of influences from different areas. Each settlement in the stratigraphic sequence belongs to "sailors" of different origins. The first mesolithic layer, attributed to the seventh millennium BC with radiocarbon dating, is characterized by a dense deposit of cardium edule shells (canestrello) and microlithic flint tools made with a stone of external origin. The closest analogies are found with a number of coastal sites in southern Italy and Sicily, the coastal strip of the Adriatic in Yugoslavia and the northwestern Peloponnese.

The next layer, described as the Aegean Linear Pottery culture, indicates a break with the past, microlith manufacture ceases, and domesticated sheep and pottery appear. The radical contrast between these two cultures suggests in 6500 BC the arrival of a different human group, probably from southern Greece. The site is soon abandoned and a period of flooding follows.

Around 6400-6300 BC the area was occupied by a population that produced impressed pottery (that is, obtained by pressing shells of cardium edule) cooked with much greater skill than its predecessors. The rosacea clay is mixed with grit and flint powder, while the outer surfaces of the pottery are smooth and decorated with fingernail impressions or stamped with a blunt instrument. Perforated handles appear and the bases of the vessels are round or flat. The shapes, technology and decoration of this pottery are very similar to those of the impressed pottery culture in western Yugoslavia (ancient phase). Along the length of Yugoslavia's eastern Adriatic coast, a series of impressed pottery sites, also found on coastal islands, line up with dates dating from a time sequence ranging from 6500 to 5500 BC (Table 17 of radiocarbon dates ). Rock shelters on the Adriatic coast of Yugoslavia have yielded cultural deposits ranging from the Palaeolithic to the Neolithic, and the latter include pottery impressed with shells, indented seals and nails.

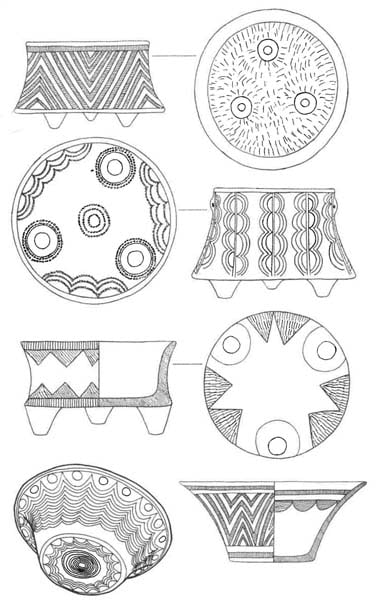

A second phase of development is documented at Smilcic, near Zadar in Dalmatia, from layers belonging to a more advanced impressed pottery culture. Smilcic was an open-air settlement with straw and mud stilt houses in which traces of domestic sheep, goat and cattle breeding remain. The millstones found here can suggest the cultivation of plants. There are large quantities of bone tools, deer antlers and chipped stone, as well as cardium, spondylus and other shells. The pottery is decorated with shell impressions, organized in bands or rocker patterns. The vessels are semi-globular and oval, while the dishes are conical, all with flattened or ring-shaped bases, generously mixed with sand and decorated before cooking.

Southern Italy (Tavoliere of Puglia, Matera and Sicily)

The Tavoliere di Puglia is a lowland, bordered by the mountain massifs of the Gargano and the Murge, which opens onto the Adriatic with an eastern area close to Manfredonia. It is thought that the first farmers arrived here carrying impressed pottery and sheep from the other side of the Adriatic. This area includes the highest concentration of Neolithic sites in Italy: they are found in caves, lake shores, coastal areas and on small hills of the plain. There are hundreds of open sites including dwellings located next to complexes surrounded by C-shaped ditches.

The largest sites, which are few in number, date from the Middle Neolithic (second half of the sixth millennium BC) and include several complexes, up to a hundred or more. These unusual concentrations were first noted in 1943 by British Army officer John Bradford when the Royal Air Force mounted several photographic reconnaissance aerial expeditions. The officer notes that it is the discovery of "one of the densest concentrations of prehistoric settlements known so far in Europe". Approximately a thousand sites have been identified from above in the Tavoliere. …

Villages surrounded by moats

Radiocarbon dates for the earliest settlements of the Impressed Pottery culture near the coast date to approximately the mid-XNUMXth millennium BCE. C. …

The large Neolithic village of Raven Pass (FIGURE 2), made up of a hundred complexes of huts surrounded by a triple moat, extends over the top of a small ridge of the Tavoliere overlooking the Celone valley. … The presence of so many ditches around the villages and C-shaped ditches inside the complexes remains a mystery. Until recently it was thought that they protected homes or confined animals. However, neither explanation seems adequate, as the dwellings were located outside the ditches and the complexes were too small to serve as animal enclosures.

Rendina, a site that can be dated to the first centuries of the sixth millennium BC, has brought to light two houses close to the C-shaped ditches. It is possible that these, sometimes three to four meters deep, served to drain and collect water in the months rainy winters and in May, just before the summer drought. The Atlantic climate of that period was characterized by average temperatures higher than the current ones (with a difference of + XNUMX°), in association with an increase in rainfall. On the other hand, wells six meters deep were found in the settlement, indicating that running water was not beyond the reach of Neolithic technology. It appears that the C-ditch did not delimit an individual farm, but served other purposes. …

Excavations a Raven Pass di Santo Tinè have brought to light a house with stone foundations up to 45 cm high. This house had an apsidal termination separated from the rest of the building by a wall. Since nothing was found inside, the function of the back chamber is unclear and we do not know if this arrangement was the norm. …

Small hut floors are attested in several other settlements, so it seems that they were the floors of ordinary dwellings. Two-room houses may have had a ritual function as in the Sesklo culture in Greece. … (FIGURE 3)

Sardinia and Corsica

Since prehistoric times, Sardinia and Corsica have been crossing points between the central and western Mediterranean world. Most of the traffic between southern and northern Italy and southern France passes through these islands, continually bringing in new items from the mainland that prevent cultural isolation.

In the fifth and fourth millennia BC, their culture, particularly that of Sardinia, is incredibly diverse and distinctive, with its own pottery and sculptural tradition and truly astonishing funerary architecture.

As in southern and central Italy, agricultural life on the islands begins towards the end of the seventh millennium BC during the impressed pottery period. According to radiocarbon dating, the oldest materials that have been found in the stratifications carried out in caves such as that of Basi and others in southern Corsica, and in Filiestru and Mara in northern Sardinia, are represented by imprinted pottery of an evolved type. The sailors who settled on these islands are assumed to have come from Tuscany via the Tyrrhenian Sea, where sites with similar pottery are found FIGURE 4.

Although spelled, wheat and domesticated animals are familiar to them, the first settlers live in rock shelters and are more hunters, fishermen and shellfish gatherers than pure farmers. Their economy is essentially based on seafood, fish, hunting of wild animals and breeding of domestic animals.

Obsidian mines in Sardinia

Sardinia flourished thanks to its obsidian. Tools made with this mineral can be found both here and in Corsica starting from the oldest Neolithic settlements up to the most recent ones. Obsidian is the prime trade item with southern France, Liguria, the Alpine region, and even across the Adriatic with Bosnia. The extraction area is Monte Arci, near Oristano, in northwestern Sardinia. The mountain in which this mineral abounds was explored more than thirty years ago by Puxeddu, who identified four quarries on different slopes, ten collection points, a certain number of workshops and 162 sites containing obsidian objects and cores. Translucent (type A) and opaque (type B) obsidian are extracted from Mount Arci, a variety that was used in these islands in the ancient Neolithic, gradually replaced by the opaque one.

Adapted from Marija Gimbutas – THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GODDESS - Vol. 1 – Alternative Press / New Balances – June 2012 – (pag. 176 – 185-186)