Taken from Luciana Percovich – Dark Shining Mothers. The Roots of the Sacred and of Religions – Venexia, Rome 2007, pp. 217-222.

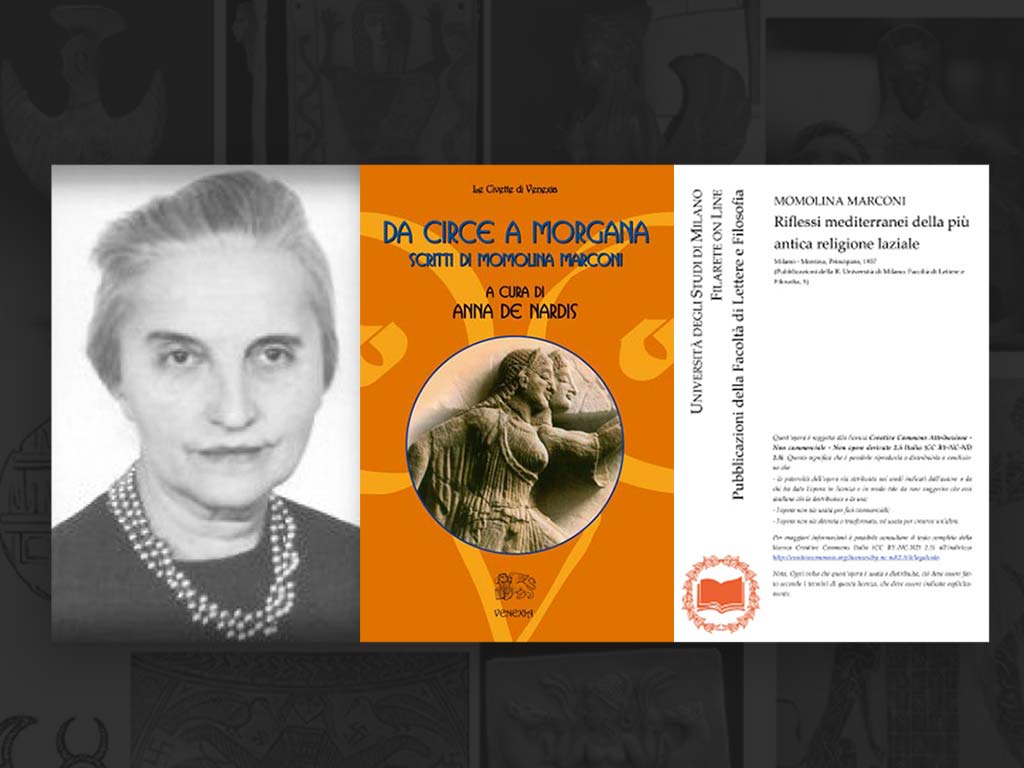

Momolina Marconi (1912-2006) dedicated her life as a scholar of Mediterranean religions to the search for primitive female representations, drawing on the iconographic and literary memory of the peoples who have left their traces on the Italian peninsula and seeking their roots and connections in the much larger area of which they were part, aware of the limited view that places the beginning of history in Classical Greece and Rome.

His main writings were published in the first half of the twentieth century: Mediterranean reflections in the oldest religion of Lazio, his first and most important book, dates back to 1939, published when he was 27 years old. Pupil of Uberto Pestalozza (1862-1966), the first Italian university professor of History of Religions (chair established in 1911 at the Royal Scientific-Literary Academy, which later became the Faculty of Letters of the University of Milan), she succeeded him in this position continuously from 1948 to 1982.

At the center of her interest, like that of Pestalozza and a small circle of scholar friends, is the rediscovery of the "femininity of the divine".

In a letter to Anna De Nardis, editor of the volume that collects many of her writings and entitled From Circe to Morgana, dated March 5, 2000, M. Marconi writes: "See that you read again the litanies of the Madonna, and tell me if there is no 'the femininity of the divine': the Madonna emerges from the androcratic environment with unexpected prestige, she is even Mater Dei…”

His was a literary education and it is on the basis of his boundless knowledge of classical texts and authors that he has created his compendium on the events, kinships and overlaps of the Mediterranean divinities. The equally vast knowledge of archaeological finds, kept in Italy and in the various museums and sites of the Mediterranean, has substantiated

her intuitions providing evidence for her ingenious and heterodox reconstruction of the ancient world of the sacred – also for her unequivocally centered on the feminine – through the iconic universe of pictorial and statuary representations.

The Great Mediterranean Female Goddess

As with Marija Gimbutas, it happened that the material - in this case already known - spoke to her by itself, through the evidence of names, myths, artefacts, allowing her to articulate a detailed reconstruction of the archetypes in which the Goddess was represented in Mediterranean world, before, during and after the stabilization of Greco-Roman culture.

In the aforementioned book, the first part entitled "The great Mediterranean female divinity" is dedicated to the typologies of the Goddess in the area of ancient Lazio and her relatives, which extend from the Black Sea and Syria to the Iberian peninsula and the northern coasts of Africa: and here is the goddess who holds or clutches her breasts, the goddess who holds or nurses the child, the potnia/mistress of herbs and animals, the goddess with the dove, the goddess Ephesia, the goddess Lucifer.

The second part, entitled "Reflections of the great Mediterranean goddess in some female divinities of the most ancient Lazio religion", describes in detail the signs and cultic characteristics of Fortuna, Bona Dea, Mater Matuta, Feronia, Diana.

We owe Momolina Marconi and her contemporary scholars the most in-depth studies on the cults of the "Italics", then transferred to the Greek pantheon adopted by Rome, and the merit of having filled the void on pre-Indo-European Italic religiosity. In the introduction of that book we also find an overview of the populations who inhabited various parts of our peninsula and their forms of worship ranging from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic, up to the emergence of the civilization of Rome in the Iron Age.

The Pelasgians: from the Iberian Peninsula to the Indo Valley

Italy, including Sardinia and Sicily, was populated in the late Palaeolithic and Neolithic by settlements that reveal a culture similar to that of the other Mediterranean islands, northern Africa and western Europe. They were the Proto-Sardinians and the Paleo-Etruscans, closely related to the Minoans and the inhabitants of the coasts of the Black Sea, up to Colchis. Colchis has a central importance in his theory: this region overlooks the Black Sea, to the east, and is the area where the Caucasus descends into the sea, with a vast territory behind it, formerly called Iberia. It is from here that Marconi derives the pre-Indo-European Mediterranean population which expanded little by little until it reached Spain, bringing with it the names of the lands of origin.

With Momolina Marconi we find ourselves before a complementary vision to that of Marija Gimbutas: in examining mainly the coastal areas of the Mediterranean rather than the central Danube area or the rest of continental Europe, the picture drawn by her hand harmoniously joins that of Gimbutas. I don't think the latter knew the work of M. Marconi, which does not appear in any of her bibliographic references, probably for the simple reason that the work of Momolina Marconi has not been circulated outside our country, as often happens to books written in Italian.

The book published in 1939 and his other writings published between 1940 and 1942, saw the light in the war years, the same ones in which M. Gimbutas attended university and graduated in the alternation of the German and Russian invasions and to think that both studied and published on distant mostly peaceful cultures in a time of such great conflicts.

Nor could Momolina know anything about Marija's work, as the results of her studies began to appear after 1956. It is therefore very interesting to see what points of contact can be found between two similar theories which developed absolutely independently, in different places , with different materials and with a different instrumentation, being basically an archaeologist and the other literate.

M. Marconi also detects the traces of a highly evolved, refined pre-Indo-European civilization, which concerns the margins of Europe overlooking the sea. It was probably a group of peoples with a common origin, the Pelasgians. He hazards hypotheses about their more remote origin (which recent studies on population genetics confirm): they were North African populations, who had pushed north and then spread in the Mediterranean basin, either by crossing the sea or going up from the east, through the Palestine and the Middle East and then settling along the territories bordering the current Black Sea.

As far as Italy is concerned, M. Marconi notes that the areas in which the oldest traces of Paleolithic settlements are found are the area of Lake Garda to the north and Liguria in the area around Genoa, while the Gargano in the south Puglia, where M. Gimbutas also excavated in the 1s. The bone remains speak of a dolichocephalic population (Chapters 8 and XNUMX), which she calls the “Mediterranean dolichocephalic race” and which reaches as far as India and Ceylon, passing through Anatolia.

This theory (recently revived on the basis of the study of Euskera, the Basque language, from a Spanish book on the origins and kinship of the Basques which finds undeniable similarities between Euskera and Etruscan, Cretan-Minoan, Iberian - Tartesic and Berber), shared by the group of scholars who recognized their master in Pestalozza, received an important confirmation in 1935-36, when the civilization of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa was discovered in the valley of the Indus river by the archaeologist Gordon Childe . The remains of those large urban settlements, dated from 2700 to 2000 BC, had very different characteristics from the subsequent Indian culture, both from an architectural point of view and from the venerated divinities. M. Marconi, like other scholars of those years, was struck by the great similarity between the Mediterranean populations and this new ancient civilization whose traces had finally been found, which confirmed the hypothesis that the Pelasgian civilization reached not only the peninsula Iberian, but also up to the Indus valley. We will soon see what linguistic evidence supports this theory, which also finds confirmation in the most ancient cultural characteristics of Egypt before the Pharaohs, rich in elements that unite India with the Mediterranean basin and with central Africa, through the shared origins at the sources of the Nile.

Returning to prehistoric Italy, to the Sicilians in particular, at least four different stratifications can be identified: a Libyan-African phase, which would testify to the first passage from Africa, followed by an Iberian phase, which marks a contact with the Ligurian-Sardinian stock ; then an Italo-Japanese-Sicilian stratum and finally the Cretan-Minoan stratum, corresponding to the influence of Crete and the diffusion of populations from that island, belonging to the same Pelasgian matrix but which had developed their own civilization by differentiating themselves.

The Siculi began their Indo-Europeanisation from a linguistic point of view starting from 1200 BC Marconi describes them as "stocky men, of small or medium stature, short neck, round head and broad face, exactly as in the metope of Selinunte: all characteristics of the type dolichocephalic" which does not develop, like the brachycephalic type, that posterior curve of the head which causes the circumference of the skull to be slightly greater (by 1,5 - 2 cm).

Throughout the Paleolithic and Neolithic there was great movement in the Mediterranean, a continuous mixing between peoples of a common original basis. In the Bronze Age, on the other hand, and in the archaic Iron Age, a people called "Villanovian" began to arrive: they were groups from the Balkan area, who moved west because, says Marconi, "pressed by great ethnic upheavals occurred in the Balkans” (here we cross the theory of the waves of the Kurgan peoples described by M. Gimbutas).

The Balkans, also inhabited by a population of the Mediterranean type, were upset by strong "pressures", of which he does not go further here, limiting himself to recording the consequences, ie the immigration of Balkan peoples to the Italian coasts. “They came by land, but often also by sea: those who arrived by land stopped in the Veneto and Mantua areas, while those who arrived by sea landed in Ancona and in the Matera area”. What differentiated them from the populations they found in Italy?

The fact that they spoke an already Indo-Europeanized language, i.e. they were not Indo-European but spoke a language that no longer belonged to the pre-Indo-European linguistic stock still dominant on this side of the Adriatic. And they brought with them another way of dealing with the dead: while the pre-Indo-European indigenous peoples buried the bodies, returning them to the earth, these immigrants were incinerators, they burned their dead.

It wasn't a question of organized hordes or numerically significant peoples, they were small groups of farmers who escaped, moved from this part of the sea. They especially didn't come on horseback and with iron swords, and yet they caused quite a stir. Then, a larger group arrived in Rimini, slowly crossed the Apennines and settled in the upper valley of the Tiber, in Tuscany and Lazio: they were the ones who later became the Latins.

“Not navigators, not conquerors, but farmers in search of land who were transported in groups across the Adriatic. These immigrants who, mind you, were neither landowners nor pile-dwellers (these two terms instead refer to what are the characteristics of some substantial autochthonous settlements of the Po valley) and founded, not on the barren and scorched plain, but along the fertile slopes of the Alban hills, groups of villages made up of round huts”.

“Unlike the Mediterraneans established in Lazio from very ancient times, the Neolithic Sicels already profoundly Ario-Europeanised, who used to sleep their last sleep with the very ancient rite of inhumation, these immigrant Villanovan peoples practiced the incineration funeral rite ...”. The Latins "are not a pre-existing people", but are constituted as a people precisely by the fact of having immigrated there, taking their name from the land that hosts them, Lazio.

“The Villanovians who immigrated to Lazio were not a different race from the Mediterranean, they were also Mediterraneans who had differentiated themselves and became Ario-Europeanized in their Balkan-Danubian locations”. That is, they had undergone contact with the arrival of the Indo-Europeans starting from 4500 (according to the dating of Gimbutas) and started a process of transformation of some of their cultural habits, including the language. Interesting detail: an area of central Italy remained immune from these Villanovan immigrations, the Adriatic area protected by the Abruzzo Apennines, "where the descendants of the ancient Neolithic lineages remained". It is no coincidence that these areas have kept their old identity, language and culture for longer; only later, when the Latins will have become Romans, will they come into contact and offer fierce resistance. It took the repeated Samnite wars, the caudine gallows and the endless military campaigns against the continuous rebellions before Rome could become master of the peninsular territory and therefore expand into the Mediterranean.

The sorceress Circe, Lady of Plants

In two other essays, Church e From Circe to Morgana, M. Marconi deals with the connection between Colchis, the Middle Ages and the British Isles, where the traces of the same megalithic civilization are numerous and evident. The center of radiation of this culture is, as already mentioned, the Black Sea. And it is precisely in the study on Church (which dates back to 1942, published in “Studies and materials in the history of religions”) which supports this hypothesis…

Taken from Luciana Percovich, Dark Shining Mothers. The Roots of the Sacred and of Religions, Venexia, Rome 2007, pp. 217-222.